Authors: Andre Esin, Julian Gerwing, Denny Ventker Sanchez, August 31, 2025

1 Definition

The universal definition of insurance describes the agreement between the policyholder and the insurer whereby the company guarantees the policyholder compensation in the event of a loss in return for the payment of insurance premiums.[1] Although such a short definition is correct, it breaks down the most essential information of the insurance concept to a minimum. In fact, scientists have been trying for decades to formulate a definition that captures insurance in its entirety. According to Zweifel et al. (2021), however, this has not yet been achieved and remains the task of science. The reason given by the authors is that the concept, which arose from business practice, is vague and ambiguous. The consequence of this is that there is not one definition, but many different attempts to define it.[2]

In the economic context, Manes (1932) defined insurance as the “elimination of the uncertain risk of loss for the individual through the combination of a large number of similarly exposed individuals who each contribute to a common fund of premiums sufficient to make good the loss caused to any one individual”[3]. Hax (1964), on the other hand, describes insurance as the exchange of an uncertain loss for a small and known fee[4], while Arrow (1965) explains that “Insurance is the exchange of money now for money payable contingent on the occurrence of certain events”[5]. It is criticized that the previous definitions did not take sufficient account of the insurance concept. For example, Arrow’s definition does not succeed in distinguishing insurance from games and lotteries, while Hax’s definition excludes mutual insurance, where the amount of the insurance premium can be variable and therefore unknown.[6]

A definition that attempts to incorporate the key features of previous definitions is that of Landes (2013):

[Insurance] is a cooperative arrangement based on risk pooling. In exchange of the payment of a premium, policyholders are compensated for part or totality of the losses incurred by the risk they are insured against. In other words, individuals decide to gather their risks and to face collectively losses. In exchange of the payment of an initial or recurring fee, they receive a partial or full compensation in case of losses induced by the happening of the risk they are insured for.[7]

As part of their insurance products, insurers cover a wide range of risks, from theft and natural disasters to death.[8] And although the insurance industry is diverse, the insurance landscape can be divided into primary insurers and secondary insurers. Primary insurance companies deal directly with customers, who can be either individuals or companies, through their distribution network or brokers. Their products can be divided into two lines: life insurance (e. g. funeral expense insurance) and non-life insurance products (e. g. car insurance).[9] The secondary insurance companies are the reinsurers. In simple terms, reinsurance can be understood as a (partial) transfer of risks from primary to secondary insurers and is therefore a global industry backup for primary insurance companies.[10] The reinsurance company bears the part of the risk that it agrees with the primary insurer and in return receives the proportionate amount of the insurance premium that the primary insurance company received from the policyholder.[11]

The reinsurance system is complex, as reinsurers also have their own reinsurers, known as retrocessionaires.[12]However, this backup system has two major advantages: Firstly, reinsurance increases the primary insurer’s cover so that risks with higher insurance values can also be insured, and secondly, it ensures the solvency of the primary insurer in order to protect the insured community.[13]

The system of insurance and reinsurance plays a special role in the global economy. Two reasons in particular highlight the importance of the insurance industry for the economy:

Insurer – and reinsurer in particular – are considered large investors, as they invest the insurance premiums they receive in the financial market. Due to their long-term investment horizons, the insurance industry is seen as a source of stability for the financial markets.[14] However, shifts or liquidation of investments by insurance companies also have the potential to move and, in extreme cases, destabilize markets.[15] The following table (cf. tab. 1), which compares the total investment portfolio value (TIPV) of insurers operating in billion euros in selected European countries in 2020 with their corresponding gross domestic products (GDPs) in billion euros in the same year, shows the large sums invested by insurance companies in the European financial markets. While the TIPV of insurers in France and Sweden almost equaled the French and Swedish GDP in 2020, the TIPV of insurers in Portugal more than doubled the Portuguese GDP in the same year.

| country | TIPV (bn. EUR) | GDP (bn. EUR) | TIPV share of GDP |

| France | 2,573 | 2,822 | 91,18 % |

| Germany | 2,000 | 3,450 | 57,97 % |

| United Kingdom | 1.877 | 2.527 | 74,28 % |

| Italy | 897 | 1.896 | 47,31 % |

| Portugal | 546 | 229 | 238,43 % |

| Sweden | 540 | 541 | 99,82 % |

Source: Own illustration based on data of Statista (2022)[16]

It is therefore hardly surprising when, as in the following cases of the insurance companies Allianz and Axa, the extensive investment plans of the insurers attract attention in the media. Allianz announced in 2021 that it would invest 2.5 billion euros in rural regions in Austria to provide them with high-speed internet[17], while Axa announced in 2023 that it would merge three of its real estate funds in Switzerland in 2024, making the company the largest real estate investor in Europe and the fifth largest in the world[18].

Secondly, without the possibility of financial protection through an insurance contract, private households and companies would be exposed to the risk of not being able to recover from a serious loss event. The obligations of insurance companies have a major financial and social impact as soon as major crises occur.[19] The importance of insurance was recently highlighted by the COVID-19 pandemic, in which insurers financially compensated for many of the consequences of the crisis.[20] According to Lanfranchri and Grassi (2021), some insurance companies have granted deferrals for the payment of insurance premiums, adjusted insurance terms in favor of policyholders and kept companies afloat by financially compensating them for temporary business losses.[21]

2 Sustainability impact and measurement

There are numerous parallels between the insurance industry and sustainable development. Both insurance and sustainability are characterized by a high degree of complexity, multidimensionality and ambiguity.[22] In addition, uncertainty plays a special role in both cases when weighing up risks and making decisions.[23] Last but not least, both fields are future-oriented and, for different reasons, have a particular interest in slowing down man-made climate change and mitigating its effects.[24]

Within the service sector, the insurance industry is characterized by a high degree of permeability and networking with companies from other sectors. It is primarily the insurers’ products that facilitate contact and the conclusion of contracts with other companies.[25] For example, it has become established in insurance practice in the context of car insurance that insurers conclude contracts with partner garages to which policyholders can be bound upon conclusion of the contract.[26] At the same time, insurers occasionally act not only as investors but also as market participants themselves in non-insurance product markets. One example of this is Allianz Real Estate, which belongs to the Allianz Group company and specializes in the construction of office properties.[27] The high degree of sector permeability, networking and the resulting broad business activities lead to a high number of different sustainability issues, which Gatzert et al. (2020) have compiled exemplary in the following table (cf. tab. 2).

| environmental issues | social issues | governance issues |

| climate change | human rights | board structure and diversity |

| renewable energy | workplace health and safety | skills and independence |

| air, water or resource | human capital management | executive pay |

| depletion or pollution | employee relations | bribery and corruption |

| changes in land use | diversity | risk management |

| … | … | … |

Source: Own illustration based on Gatzert et al. (2020)[28]

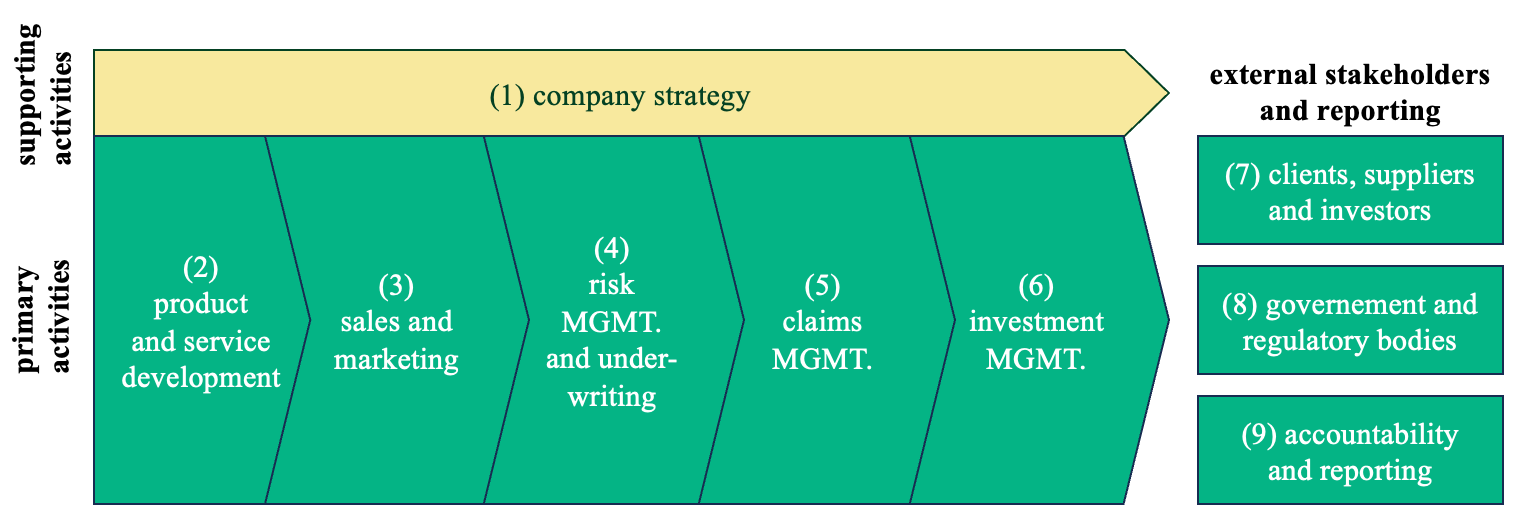

As the sustainability issues listed in the table do not relate exclusively to the core business of insurance and reinsurance companies and are partly generic in nature (e. g. human rights and executive pay), this article focuses on the primary activities and direct stakeholders of the insurer’s value chain with regard to sustainability issues. The relevant sections of the value chain are highlighted in green in the following figure (cf. fig. 1).

Source: Own illustration based on Barrera & Wagner (2023)[29]

From the triple bottom line to corporate social responsibility and the ESG approach, there are various sustainability concepts with which managers try to promote sustainability in their own company.[30] In terms of corporate strategy development and the measurability of sustainability performance, the ESG approach is used in particular in business practice.[31] ESG is an acronym made up of the terms “environmental”, “social” and “governance”. These terms are also the dimensions along which sustainability is considered and its impact measured.[32] The following section examines the influence of the insurance industry on sustainability, taking ESG criteria into account, and explains how this influence can be measured.

2.1 Environmental

In the area of the environmental dimension of sustainability, the literature emphasizes the influence of the insurance and reinsurance industry on sustainability through climate risk insurance and sustainable investing, which is why the following subchapters focus on these two topics in particular.

2.1.1 Climate risk insurances

Across the categories of the insurance value chain, the literature highlights the major influence of the insurance industry on sustainable development.[33] From the second to the fifth category of the insurance value chain, the increasingly noticeable effects of climate change are the main topic with regard to environmental sustainability. Non-life insurance companies in particular enable their policyholders to insure themselves financially against climate-related hazards in selected insurance products. For example, vehicle owners can insure their cars against storm, hail, lightning and flood damage.[34] Depending on the insurance company, customers can insure both their household contents and their residential building against the financial consequences of flooding, snow pressure, avalanches, subsidence, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions as part of their household contents and residential building insurance by agreeing natural hazards clauses or by taking out separate natural hazards insurances. Companies can also insure against climate-related business interruptions caused by storms, flooding or hail.[35]

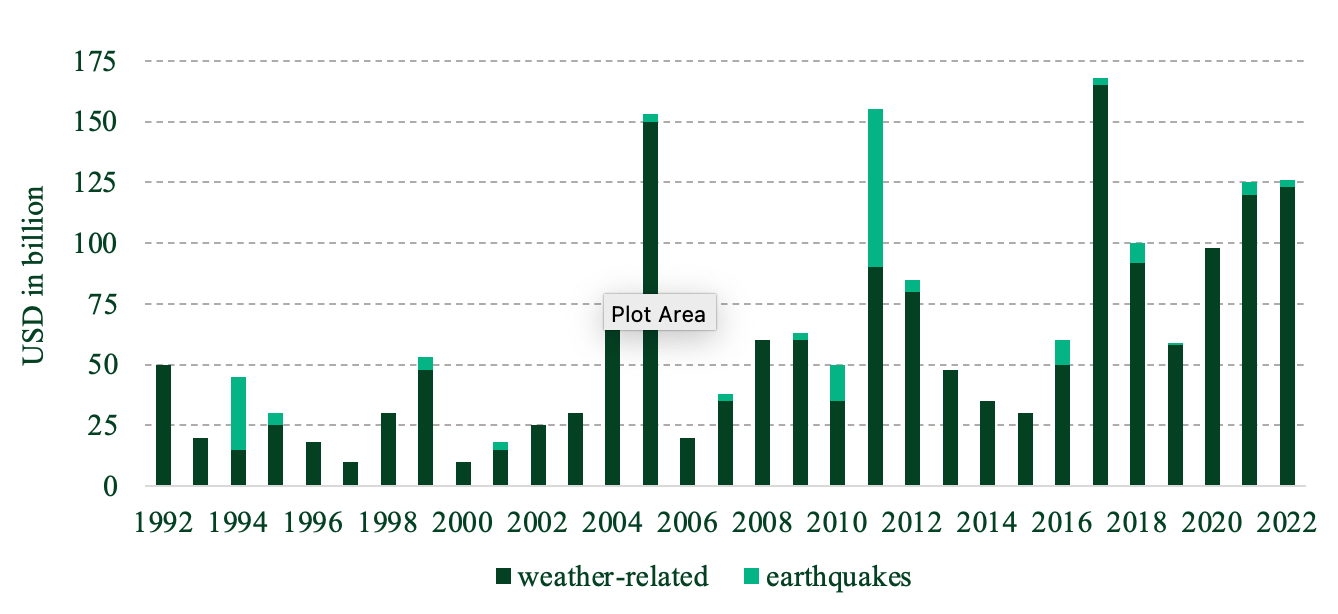

The reinsurer Swiss Re calculated that from 1992 to 2022, global cumulative insured losses from natural catastrophes increased by an average of five to seven percent annually. The second figure, which shows the increase in insured losses from natural catastrophes over the period in question, shows that although the annual costs in USD billions are volatile, the consequences of climate change are having an increasing impact on insurers’ costs. Insurance companies had to pay a maximum of USD 55 billion each in the years 1992 to 2000, while expenses for insured climate damage amounted to at least around USD 100 billion each in the years 2020 to 2022 (see fig. 2).[36] The European Environment Agency (2022) estimates that between only one quarter to one third of all global climate damages are insured.[37] Swiss Re confirms this assumption by estimating climate-related insured losses at USD 125 billion and global economic losses from climatic natural disasters at USD 275 billion in 2022[38], resulting in a significant insurance protection gap.[39]

Due to the average increase in natural disasters, it is hardly surprising that the demand for weather-related and nature-aligned insurance products is also increasing worldwide. The research results of Barrera and Wagner (2023) show that the demand for climate-related microinsurance products in developing countries is higher than the demand for conventional natural hazard insurance in industrialized countries, as the former are more affected by the effects of climate change and the damage caused by environmental disasters poses a greater risk to the existence of policyholders in developing countries.[40] A global insurance offering therefore also fulfills a social function. It helps to ensure that the existence of those affected by the consequences of climate change is financially secured by the insurance premiums of the insured community.[41]

Source: Own illustration based on Swiss Re Institute (2023)[42]

Climate risk insurances have existed for decades, but have only received special attention in recent years with the effects of advancing climate change.[43] Both the Paris Agreement and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction address insurance as a key tool for mitigating the financial consequences of climate change. Furthermore, the topic gained additional importance when the G7 summit in Elmau in 2015 decided to launch a “Climate Risk Insurance Initiative” and the G20 summit in 2017 acknowledged the relevance of a “Global Partnership for Climate and Disaster Risk Finance”.[44]

Climate risk insurances are both preventive, as they protect policyholders from existential losses, and transformative, as they reduce the premiums of other smart climate risk insurances in the long term with their increasing range of products.[45] Both lead to an increase in the resilience of the insured community. The impact of climate risk insurances is difficult to quantify, but both the European Insurance Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) and research emphasize that the aim of the insurance industry should be to reduce the insurance protection gap by increasing the supply of affordable climate risk insurances.[46]

2.1.2 Sustainable investing

The insurance industry influences environmental sustainability through the sixth to ninth category of the insurance value chain via investment assets, e.g. in the form of funds. Insurance and reinsurance companies are among the largest institutional investors in the global economy, particularly due to pension funds.[47] In recent years, academic literature has increasingly focused on the investment practices of the insurance industry and has repeatedly referred to the inclusion of ESG investment practices. The importance of sustainable investing has become increasingly important for the insurance industry, especially in recent years, as investors’ interest in sustainable investment decisions has increased.[48]Until investors began to take sustainability aspects into account in their investment decisions, the insurance industry was criticized for a long time for its predominantly financially driven investment decisions. For several decades, they invested primarily in climate-damaging sectors and companies such as the tobacco and arms industries, which historically produced above-average market returns.[49] Increased awareness of sustainability and ever more stringent reporting requirements have prompted many insurers to rethink their approach, so that investment decisions are no longer based solely on economic criteria, but also on ESG criteria.[50] Companies that do not base their investment decisions on ESG criteria are increasingly exposed to a higher reputational risk.[51]

Gatzert and Reichel (2022) observe that in recent years, insurers have primarily opted for ESG integration, impact investing and the exclusion of investments that are generally considered unsustainable in their investment strategies.[52]The findings of Golnoraghi (2018), who surveyed 62 C-level executives from 21 international insurance and reinsurance companies as part of the Geneva Association survey, support these observations.[53] While the ESG approach involves making investment decisions based on ESG factors,[54] impact investing describes the intention to invest in companies, organizations or funds in order to achieve a measurable, positive social or environmental impact in addition to a financial return.[55] Gatzert et al. (2020) describe how several insurers from the coal industry have recently disinvested and Allianz announced in 2018 that it would no longer insure this industry in future.[56] Since then, Allianz has stated in its sustainability reports that investments by Allianz Global Investors (Allianz GI) are ESG-compliant and impact investing-oriented. In addition, the company reports annually in its sustainability report on the amount accumulated and disinvested from the coal industry since 2015.[57]

“AllianzGI ESG risk-focused portfolios incorporate material ESG risk considerations into the investment process across all asset classes to seek enhanced riskadjusted returns without restricting the investment universe. […] AllianzGI Impact-focused approaches aim to support investors who want to enable positive change while generating a return.”[58]

However, Rempel (2020) found that these measures have had a negative impact on returns for some pension funds. Although a large number of insurers have divested industry-wide from tobacco and nuclear weapons, certain industries such as the fossil fuel sector are often unaffected by this, as insurance and reinsurance companies expect high returns in this sector to compensate for the lack of returns from the divested industries. As a compromise, company-specific conditional divestment often takes place in the fossil fuel sector, whereby individual companies are removed from investment portfolios as soon as they fail to meet certain ESG requirements.[59]

The most relevant sustainability guidelines for investments in the insurance industry are the principles for responsible investment (PRI), which aim to achieve sustainable global finance by integrating ESG factors into investment portfolios.[60] As the principles are qualitative guidelines, the environmental and social impact of sustainable investing is generally difficult to measure, depending on the investment strategy. In order to satisfy investors’ demand for ESG information, rating agencies have specialized in ESG in recent years. The ratings of data providers such as S&P Global, MSCI and Sustainalytics are represented in numerous sustainability reports of insurance and reinsurance companies.[61] They compile sustainability information from primarily financial institutions and evaluate it along the three ESG dimensions of environmental, social and governance.[62] MSCI, for example, aggregates company information on 35 ESG issues and rates them using a points system from 0 to 10,000. For a better overview, the provider has also scaled and described the points scale so that companies with the lowest score of 0 to 1,429 are rated as “CCC – Laggard” and companies with the highest score of 8,571 to 10,000 are rated as “AAA – Leader”.[63] According to Brandon et al. (2021), upgrades in relevant rankings would have a positive impact on stock returns, while downgrades would have a negative impact.[64] In addition, Cheng et al. (2022) show that ESG ratings above the industry average have a positive impact on corporate reputation, which is why companies have a particular interest in making their investment portfolios ESG-compliant.[65]

2.2 Social and Governance

It is not always possible to make a clear distinction between the sustainability dimensions of social and governance, nor does it make sense to do so with regard to the insurance industry, as sustainability issues influence each other and can rarely be considered in isolation. In the literature, gender equality is discussed in the context of both the social and the governance dimension.

Researcher attached particular importance to gender equality in two areas of the insurance industry in recent years. Firstly, there are differences in the treatment of the sexes when concluding an insurance contract, and secondly, women are underrepresented both as employees and as managers. While the former topic concerns the second to fourth as well as the eighth category of the insurance value chain, the underrepresentation of women in insurance professions is an issue that is of importance to external stakeholders.

2.2.1 Product-related gender equality

In the European Union, unisex tariffs have applied to all newly concluded insurance contracts since December 21, 2012. A unisex tariff is an insurance tariff that does not use the policyholder’s gender as a tariff criterion, although it does influence the risk assessment. Insurance companies in European member states previously used gender as a rating criterion, which led to different insurance premiums for men and women.[66] For example, before the introduction of unisex tariffs, men paid higher premiums for endowment and term life insurance policies, as men have a lower average life expectancy than women, meaning that agreed insurance benefits are more likely to be paid out for male policyholders. Female policyholders, on the other hand, paid higher health insurance premiums, which the health insurer justified with the longer life expectancy of women and their more frequent visits to the doctor on average. In addition, although young men had to pay higher insurance premiums for car insurance than young women, women paid higher premiums on average overall.[67]

In many countries outside the European Economic Area, however, the gender of the policyholder is still taken into account as a tariff criterion. For example, Pernegallo et al. (2024) found that women aged 25 and over in the United States have to pay higher insurance premiums for their car insurance. The authors were unable to identify a statistically significant justification for women’s higher average car insurance premiums. Instead, a number of scientific studies show that women tend to drive more carefully than men.[68] Although the introduction of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in the USA banned the calculation of premiums based on gender in health insurance, women still pay higher premiums than men for their life insurance policies.[69]

Since the introduction of unisex tariffs, there has been debate in the literature from various perspectives as to whether these tariffs are fair compared to the previous bisex tariffs, as the gender with the lower risk cross-subsidizes the gender with the higher risk, depending on the insurance.[70] Cather (2023) criticizes the fact that statutory unisex tariffs could promote regulatory adverse selection. In the context of insurance, adverse selection describes the phenomenon that high-risk individuals want to take out insurance more often than low-risk individuals because they have a greater need to cover their risk. The insurer’s restriction in determining risk could lead to a proportionally high number of high-risk individuals within an insurance tariff. This could limit the tariff’s viability and harm the community of policyholders, as the insurer is not allowed to collect all the pricing characteristics required to determine the risk and include them in the pricing. This could promote evasive strategies on the part of insurers, such as concentrating on the lower-risk gender when approaching customers or rejecting insurance applications from the higher-risk gender in order to ensure the viability of the tariff.[71]

2.2.2 Work-related gender equality

Another challenge facing the industry is the significant underrepresentation of women in management positions (cf. tab. 3). Although at least 50 percent of the people working in the insurance industry on the continents listed in the table are women, the percentage of women has decreased between 2010 and 2020, with the exception of Africa (cf. section a). At the same time, the number of new female hires has decreased worldwide (cf. section b). Although the growth rate of women in management positions in Asia and Europe continues to be positive, at around 36 percent women only hold just over a third of all management positions (cf. section d). Last but not least, women hold a third of board positions in insurance and reinsurance companies in Europe, while the percentage share in the other continents is significantly lower (cf. section e).

| 2010 | 2020 | Δ 2020/2010 | |

| Section A: Women employees | |||

| Africa | 56.67 | 59.74 | 5.42 |

| America | 60.42 | 55.26 | -8.55 |

| Asia | 54.48 | 50.23 | -7.79 |

| Europe | 51.60 | 50.36 | -2.39 |

| Total | 55.79 | 53.90 | -3.39 |

| Section B: New women employees | |||

| Africa | N. A. | 12.72 | N. A. |

| America | 37.00 | 52.12 | -15.88 |

| Asia | 94.85 | 62.08 | -34.55 |

| Europe | 48.87 | 46.19 | -5.48 |

| Total | 71.86 | 43.28 | -39.77 |

| Section C: Women Managers | |||

| Africa | 55.56 | 36.33 | -34.61 |

| America | 49.30 | 41.88 | -15.04 |

| Asia | 5.78 | 30.81 | 433.43 |

| Europe | 30.52 | 34.93 | 14.44 |

| Total | 35.29 | 35.99 | 1.98 |

| Section D: Board Gender Diversity | |||

| Africa | 8.89 | 24.11 | 171.26 |

| America | 14.13 | 21.60 | 52.91 |

| Asia | 2.29 | 12.83 | 459.77 |

| Europe | 16.69 | 34.32 | 105.60 |

| Total | 10.50 | 23.22 | 121.09 |

Source: Own illustration based on Birindelli & Iannuzzi (2022)[72]

Birindelli and Iamnuzzi (2022) also compared the gender equality figures of insurance companies with those of banks within the financial sector and found that the proportion of women in the insurance industry is lower than in the banking industry, the insurance industry has a lower growth rate of new women employees and fewer women hold management positions in insurance companies. The insurance industry only marginally outperforms the banking industry in terms of board gender diversity. The authors come to the conclusion that the banking sector has so far been more successful than the insurance sector in establishing gender equality.[73]

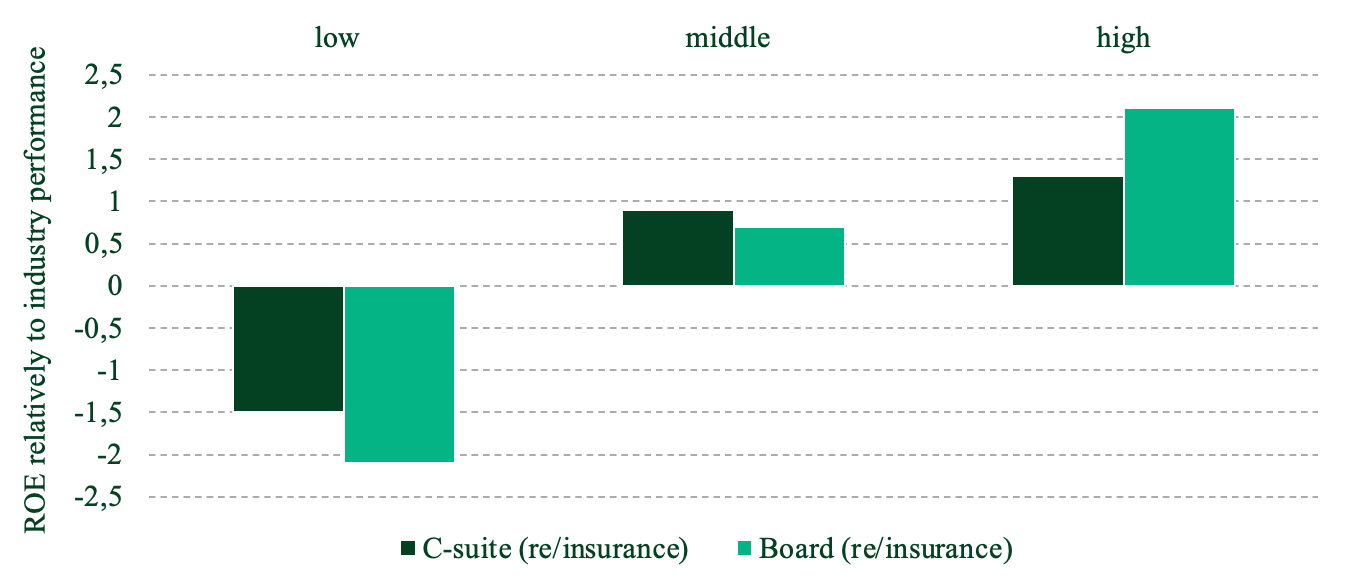

In the professional sphere, gender equality is generally measured in gender quotas, whereby for social reasons the aim is often to achieve an almost equal distribution of men and women in management positions.[74] However, gender parity in management positions makes sense not only for social reasons, but also for economic reasons, as the analysis of the reinsurance company Swiss Re shows (cf. fig. 3).

Source: Own illustration based on Swiss Re Institute (2021)[75]

The diagram is based on a sample of 170 insurance, reinsurance and insurance brokerage companies for the period 2002 to 2019 and shows the average return on equity (ROE) relative to the annual industry performance for companies with different levels of representation of women in board or chief-suite (C-suite) positions. It can be seen that companies with the lowest level of representation of women at C-suite and board level perform below average in an industry comparison, while companies with the highest proportion of women in the C-suite and board perform best.[76]

3 Sustainability strategies & measures

Climate risk insurances, which compensate for the financial impact of climate-related hazards, were discussed in the second chapter. However, this type of insurance deals much more with the symptoms than the actual causes of man-made climate change. The literature has recently recognized this fact and addressed the sustainability transformation of the insurance industry through the green insurance concept. This strategic approach as well as measures, technologies and tools that improve sustainable development in the insurance industry are discussed in this chapter.

3.1 Green insurance approach

The literature has been dealing with sustainable products and services in the insurance industry for some time. In 2009, Mills examined more than 200 insurers and related organizations and identified 643 real examples of sustainable insurance solutions worldwide.[77] And although these products can be subsumed under the current understanding of green insurance, the concept has only attracted particular attention in recent years, meaning that there is still no clear definition.[78]

In principle, however, green insurance is seen as an innovative approach to promoting sustainable business practices in the insurance and reinsurance industry. In addition to compensating for losses caused by environmental pollution events and climate catastrophes,[79] the concept includes emission-reducing inventions that adapt to the changing global climate and its conditions.[80] These now include numerous insurance products that are available in most green economies. Zona et al. (2014) list global weather insurances, green building insurances and renewable energy insurances as examples.[81]Both central banks and global regulators emphasize the importance of green insurance products to mitigate climate change.[82] Since the insurance and reinsurance industry has relatively little direct influence on man-made climate change compared to the manufacturing industry, but has a major influence on the behavior of other industries and private households through its products, the literature sees green insurance products as having the potential to bring about a transformation to a sustainable global economy through the design of sustainable products.[83] According to Chen et al. (2019), green insurance products could thus strengthen environmentally friendly policies and have a significant influence on the development of inspection, testing, evaluation and approval systems.[84]

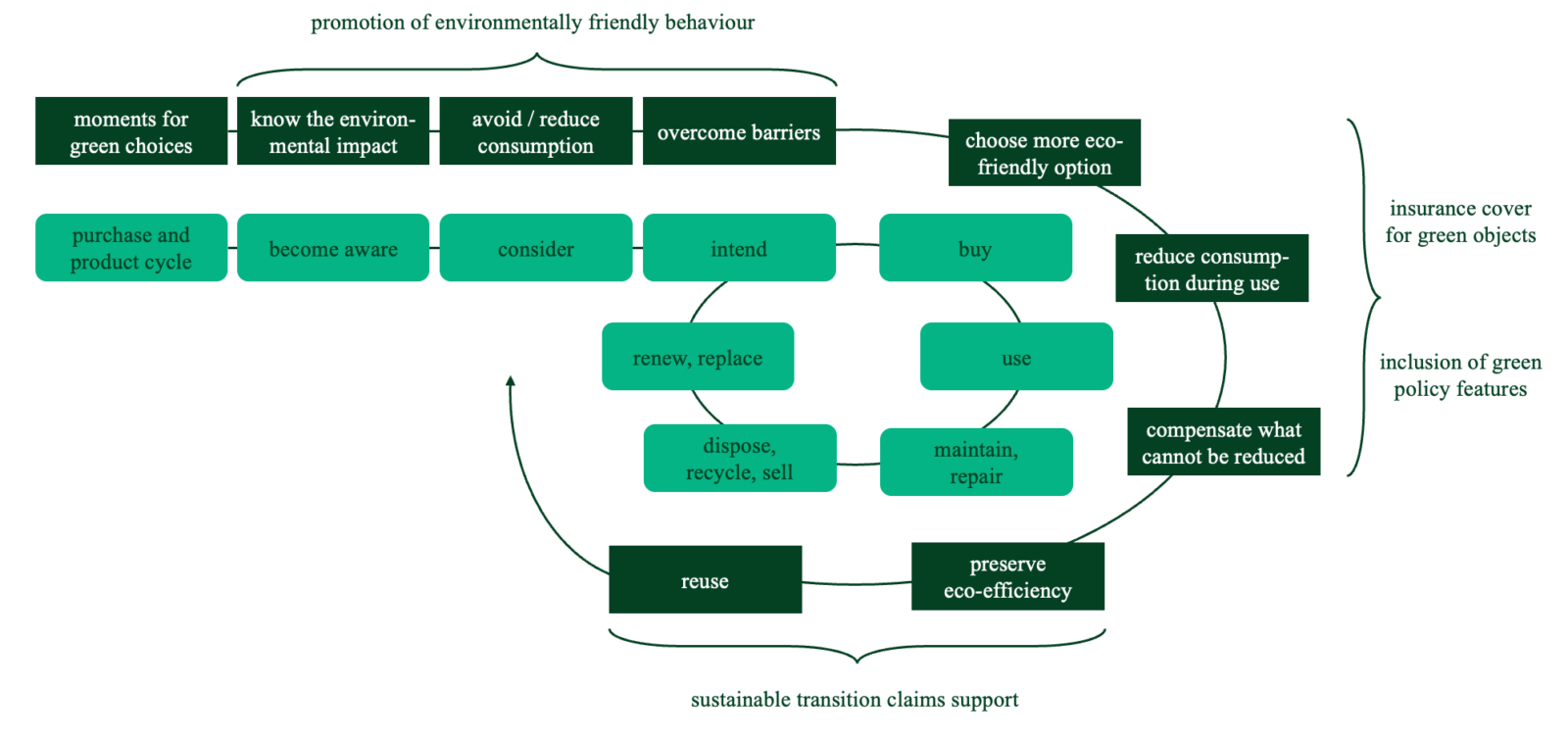

Stricker et al. (2022) have developed a roadmap based on the research findings of Pugnetti et al. (2022) along categories two to five of the insurance value chain (cf. fig. 1), which includes the principles of green insurance. It is intended to provide practical support to insurance and reinsurance companies in implementing sustainability in the core elements of the value chain. The purpose of the roadmap is not only to improve the climate resilience of insured sectors and private households, but also to take an active role in proactively driving forward the sustainability transformation. The authors define five milestones per category that need to be considered during implementation. At the same time, the authors name exemplary metrics that insurance companies can use to measure the progress of implementation (cf. fig. 4).

| Roadmap | |||

| insurance cover for green objectsinclusion of green policy featuressustainable transition claims supportpromotion of environmentally friendly behaviourdialogue with customers | integration of sustainability in risk leadership and analysisreview of global risk objectivesdefinition of local tolerance levelsrisk monitoring and reportingexternal environment monitoring | ESG due diligenceassessment criteria and metricsinclusion of sustainability in risk assessmentdefinition of decision-making processesdelivery of ESG expertise | sustainable leadership program accompanimentgreenhouse gas emissions inventorybaseline metricsmeaningful targets and associated actionsprogress measurement, actions on deviations and reporting |

| Examples of metrics | |||

| share of products reviewed and updatedshare of premiums from sustainability productsnumber of customers participating in resilience programs or receiving prevention services | share of policies reviewed and updated to reflect ESG issuesnumber and types of ESG factors included in ORSA scenariosshare of risks in inventory reviewed for ESG exposure | number of referred ESG risksrate change of sustainable versus classical productsloss ratio on sustainable versus classical products | GHG emission reduction per employeeshare of suppliers in accordance with vendor code of conductshare of damaged objects repaired versus placed, or replaced with environmentally friendly alternative |

Source: Own illustration based Stricker et al. (2022)[85]

As the individual milestones and metrics in the diagram are self-explanatory, the implementation of green insurance will be explained using the example of car insurance. In the case of car insurance, the insurance company must be aware of the influence that certain types of vehicles have on sustainability. The risk of damage occurring must still be calculated and reflected in the insurance premium, but the risk should no longer be considered in isolation. The impact of the insured object on the environment and society must also be taken into account.[86]

For example, cars with a battery have lower emissions over their entire lifetime than cars with combustion engines.[87]Nobanee et al. (2021) therefore recommend that insurance companies grant drivers of electric cars a significant discount on their car insurance. This would also create financial incentives for drivers to opt for an electric vehicle despite the higher purchase price.[88] As part of risk management, consumer behavior can be influenced by rewarding environmentally friendly use of the insured object. In the case of car insurance, this would mean that particularly environmentally friendly driving, e.g. avoiding fast driving and using the vehicle less often, could be rewarded with discounts or refunds.[89] Although insurance companies generally include how many kilometers the policyholder drives per year in the insurance premium, driving style has not been taken into account to date and can be evaluated using a telematics device in the car.[90] If the vehicle breaks down, not only the residual value and repair costs should be considered in future. If the repair costs are higher than the vehicle value before the damage occurred, insurance companies speak of an economic total loss, meaning that the vehicle value before the damage occurred is paid out instead of the repair costs.[91] However, such a simple calculation does not pay tribute to the impact on the environment and society. An insurance company that internalizes the green insurance principles takes recognizes the environmental impact of a repair or a new purchase. For example, it is quite possible that it is uneconomical to repair a vehicle, but from an environmental and social point of view it may make sense to repair the vehicle because the environmental costs caused by scrapping the old vehicle and the production of the new vehicle are taken into account. Thinking in perspective and on a larger scale, the repair of vehicles whose repair is uneconomical at first glance could also be worthwhile for insurance companies, because the systematic and large-scale repair of vehicles can reduce the impact on man-made climate change, for example because vehicles are built more robustly and more modularly, and environmental disasters occur with less frequency.[92]

Source: Own illustration based on Stricker et al. (2022)[93]

The fifth figure structures the steps mentioned in the example of motor vehicle insurance and provides insurance companies with recommendations on how they can use their immaterial products to influence a sustainability-oriented approach to material products in order to bring about a cross-sectoral change in sustainability. The concept covers all relevant implementation steps of green insurance, from the initial definition of the green goals to be achieved with the insurance product, to the creation of incentives for policyholders to use their insured items sustainably, to sustainable claims support that includes not only economic, but also ecological and social indicators.

Stricker et al. (2022) emphasize that the green insurance approach can help the insurance industry to position itself sustainably. However, the authors also point out that their concept only covers the insurance product side and that further research is needed for an investment-side concept that internalizes the principles of green insurance. Last but not least, the strategic perspective must not be ignored, which (1) analyses the current industry and company situation with regard to sustainability problems, (2) sets strategic and functional goals for a general strategic orientation, (3) formulates actions and metrics and (4) regularly measures and evaluates the success of sustainability measures in order to support the organization in its transformation.[94]

3.2 Measures, technologies and tools

The previous chapter used the holistic green insurance approach to explain the preliminary considerations and decisions that insurance and reinsurance companies need to make in order to position themselves sustainably. This chapter will focus on specific measures, technologies and tools that can support the insurance industry in bringing about a sustainable transformation of the sector. Due to the complexity and broad scope of the measures, technologies and tools, they will be systematized and compiled with regard to the specific sustainability impact in the insurance industry. The aim is to (i) briefly explain the measure, technology or tool, (ii) explain its use and (iii) its sustainability benefits and (iv) discuss the advantages and disadvantages of alternative measures.

3.2.1 DLT/blockchain and smart contracts

i. Brief explanation of the technology

Distributed ledger technology (DLT) is a digital record of information or transactions that are shared in real time and forgery-proof in a cryptographically secured and decentralized peer-to-peer network of participants.[95] The status of the ledgers is checked and updated by the network participants, known as nodes. If one of the network participants proposes a new transaction, the other network nodes check the proposed change to the ledgers using a computer algorithm in order to reach a consensus on the state of the ledgers.[96] The consensus algorithm of DLT networks makes it possible to exchange data and capital without centralized intermediaries.[97]

Even though blockchain is often used as a synonym for DLT[98], blockchain is a variant of DLT in which the current data state is also confirmed and verified on a shared ledger by the participants in the network without the need for a single organization.[99] A blockchain is characterized by the single source of truth, which means that a blockchain is (1) distributed, (2) decentralized, (3) tamper-resistant and (4) transparent. Although conventional tried-and-true database solutions can also have some of these characteristics, they form the foundation of the blockchain.[100]

Both DLT and blockchain consume a relatively large amount of energy, because during the validation process the nodes of the network have to solve sophisticated mathematical equations, which results in high CO2 emissions.[101] The biggest difference between DLT and blockchain is that blockchain only uses blocks of data that are chained together to create the ledger. DLT, on the other hand, also incorporates other design principles to create the ledgers.[102]

Smart contract is an umbrella term for self-executing programs that are used on a blockchain.[103] As soon as previously defined criteria are met, smart contracts trigger a set of business logic that the network participants agree to. In this context, contract means that the network participants have reached an agreement without referring to contracts in the legal sense. However, smart contracts can include legal contracts or agreements.[104] Smart contracts are of particular importance for the blockchain, as they extend the functions of the blockchain and enable the implementation of various practical use cases.[105]

ii. Use cases

The insurance industry recognized the potential of DLT, blockchain and DLT very early on. At the same time, the financial literature adopted these technologies very early on, which is why there are already a number of use cases for the insurance industry. Almost all practical approaches have three things in common: (1) The technology can be used to reduce intermediaries and the associated disadvantages. (2) A temper-resistant record is created in which the network participants are on an equal footing and the system is trusted by all participants. (3) Leaner processes, e.g. through a standardized application procedure via smart contract, can reduce operational costs and frictions in the insurance value chain.[106]

Tarr (2018) sees three areas of application for DLT/blockchain and smart contracts: fraud detection and smart contracting. Insurance companies could benefit from the single source of truth principle in terms of fraud detection, as a decentralized digital repository can independently verify the authenticity of customers, insurance policies and payment transactions by providing a complete historical record. Insurers can, for example, immediately identify duplicate claims calculations due to double insurance and the suspicious persons or organizations involved. In practice, the first companies are already using blockchain technology to combat fraud.[107] The start-up company BlockVerify aggregates information on transactions for products such as electronic goods, pharmaceuticals and luxury items in a blockchain. The products are given an NFC tag, which is used by employees along the entire supply chain to bundle information such as data on transfers, ownership, locations and other relevant distribution data on the blockchain and verify product authenticity.[108]

Another field of application is smart contracting.[109] PwC observes that the application process as well as the administration of contracts is quite time-consuming and that DLT could be used to reduce administrative and operational costs by automating documentation on an encrypted database based on the blockchain.[110] In particular, administrative activities such as the announcement of a new address for household contents insurance, the notification of marriage for the consolidation of personal liability insurance or the change in annual mileage could be transmitted by policyholders via the blockchain, triggering a smart contract program that independently changes the pricing features of an insurance policy within the previously defined framework without tying up the insurer’s personnel capacities.[111]

iii. Impact on sustainability

DLT/blockchain and smart contracts could have a positive impact on all ESG dimensions. Although a not inconsiderable proportion of the literature criticizes DLT/blockchain for being energy-intensive, Sedlmeir et al. (2020) examined the extent to which this applies to all DLT/blockchain technologies in their work. They note that blockchain technology is by no means homogeneous and that general statements about the energy consumption of a blockchain should be treated with caution. Bitcoin and the energy-intensive mining process in blockchains would dominate the discussion and obscure the fact that it is possible to set up eco-friendly blockchain networks in the business environment.[112]

As already explained, a blockchain and its single source of truth concept could reduce cases of fraud, as the parties involved can view relevant information at any time and cannot manipulate it. Insurance companies around the world have difficulties with insurance fraud cases. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) estimates that in the United States alone, insurers incur costs of USD 40 billion per year as a result of fraud. For a US family, this results in around USD 400 to 700 higher insurance premiums.[113] The Insurance Fraud Taskforce in the UK also reports that insurance companies incur losses of more than three billion pounds, resulting in an average premium increase of 50 pounds for policyholders.[114]

DLT/blockchain and smart contracts are particularly relevant in closing the insurance protection gap discussed in chapter two of this article. Anguiano & Parte (2023) explain that reducing costs through the use of blockchain could enable insurance companies not only to reach underinsured countries, but also to expand their offerings to include microinsurance for marginalized groups within countries that are tailored to the needs of these groups and protect their livelihoods. Particularly in countries where risk data is scarce and corruption rates are high, microinsurance on blockchains could foster both provider and buyer trust to close the global insurance protection gap and protect those people most affected by the consequences of climate change. [115]

In countries such as Mongolia and Ghana, which have since implemented regulatory reforms to improve microinsurance cover, the efforts have led to an increase in insurance cover for existential risks. In Ghana, for example, 65% of insurance policies concluded in 2019 were microinsurance policies following the implementation of the reforms.[116]

In practice, only a few insurance companies currently use the blockchain in combination with the blockchain. One well-known example is the use of blockchain and smart contracts by the insurance company Allianz. As part of a pilot project, the insurance company transferred insurance contracts allocated to selected regions to a blockchain and configured the smart contracts located there in such a way that insurance benefits can be paid out to the affected policyholders immediately in the event of a major environmental disaster. The use of blockchain and smart contracts is a lesson from the past. In 2010, storm Xynthia caused widespread damage, particularly in Europe, which meant that policyholders were no longer in possession of their insurance documents. As a result, policyholders had to wait up to a year to receive their insurance payments.[117]

iv. Alternative measures

Depending on the region, there are different database solutions in the insurance industry to prevent insurance fraud. In Germany, the German Insurance Association imitated the German insurance industry’s information system (HIS). This database is managed centrally by the company Informa HIS and is a joint warning and information database for insurance companies. The system is used to report atypical claims frequencies, anomalies in claims or benefit cases and concluded life and disability insurance policies. Insurers can submit entries to the system themselves, request information as part of the risk assessment or have entries deleted from the system. The system covers both life and non-life insurances.[118]

The system has both advantages and disadvantages. The system has been in place since 2011, so many efforts have been made over time to link the system to the software solutions of the respective companies. At the same time, the database is not maintained by the insurers themselves, but by Informa HIS, so that the insurance companies do not incur any costs for maintenance or upkeep. However, there is criticism that the database is a blacklist of people without them even knowing that they are stored in the database. Although policyholders can now request a self-disclosure, only very few people make use of this option. Unlike with a blockchain, the data is neither forgery-proof nor validated. The insurance companies have to trust that the previous insurer has provided correct information without being able to check this. However, the policyholders themselves can only draw attention to incorrect entries if they find out about them. The fact that these databases are not distributed can increase insurers’ mistrust of insurance companies.[119]

3.2.2 Big data and AI

i. Brief explanation of the technology

Big data is defined as a large amount of data that can only be stored, processed and analyzed at great expense due to the size and complexity of the data.[120] At the same time, the term big data is used to describe the analysis of data with the aim of making the data economically usable. [121]

Artificial intelligence (AI) is a field of research that deals with solving problems that are linked to human intelligence. Topics often include learning, problem solving and pattern recognition. AI makes it possible to make machines more intelligent so that they can act independently according to a pattern.[122]

The close connection between big data and AI is repeatedly emphasized in the literature. The use of machine learning and deep learning algorithms in artificial intelligence in combination with big data enables AI models to learn faster and increases the accuracy of AI applications.[123]

ii. Use cases

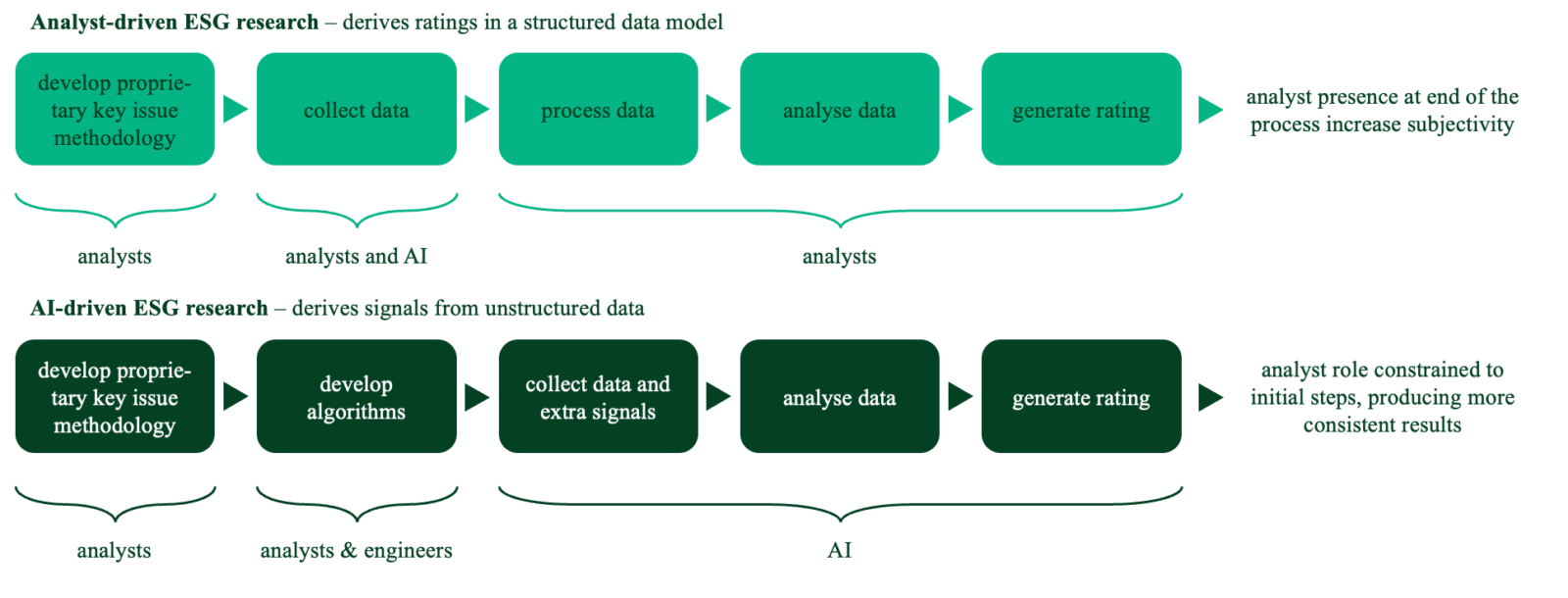

In the context of the insurance industry, an almost infinite number of different areas of application of big data and AI are being addressed.[124]A number of studies deal with big data and AI with regard to ESG rating. Svanberg et al. (2023) refer to several studies that have come to the conclusion that the inclusion of ESG ratings for investment decisions can make sense in order to assess the sustainability impact of companies and financial products that are anything but accurate according to conventional ESG ratings.[125] Hughes et al. (2021) build on these findings and have developed an AI-driven model that accesses a large amount of unstructured data in order to generate an ESG rating that is as objective as possible and based on many data points (cf. fig. 6).

Source: Own illustration based on Hughes et al. (2021)[126]

The model by Hughes et al. shows that the development of an ESG rating using big data and AI produces a more consistent and objective result because the aggregation, analysis and generation of the rating is carried out on the basis of algorithms.[127]

Chapter two of this article also criticized the fact that insurance companies take gender-specific characteristics into account when calculating risks. In the case of car insurance, women have to pay a higher insurance premium on average, although research has found no evidence that women cause higher claims than men.[128] In life and health insurance, men and women represent a different risk, but the literature criticizes whether the inclusion of gender in terms of social criteria is sustainable.[129] Some researchers see big data and AI as a solution to avoid evasive strategies on the part of insurance companies, such as discriminating against one gender in the application process. Berthelé explains that big data and AI can be used to identify relevant risk characteristics and, on this basis, derive pricing features that exclude gender and still enable insurance companies to calculate the risk precisely.[130] Internet of things innovations that are connected to the internet and transmit risk-relevant data to the insurance company for risk assessment are often mentioned in this context. Spender et al. (2019) explain that wearables such as a smartwatch could, for example, determine how many steps a policyholder takes on foot or by bike. This information would then be transmitted to the health insurance company. If the targets agreed with the health insurer are achieved, a discount on the health insurance could be granted.[131] Eling and Kraft, in turn, recommend that car insurers offer telematics tariffs that evaluate not only the kilometers driven but also the policyholder’s driving style when calculating the risk and incorporate this into the premium calculation.[132]

iii. Impact on sustainability

An AI-driven ESG rating could eliminate the subjective influence of rating agency analysts. Data could be collected and evaluated in real time. If the algorithms are publicly accessible, any interested party can understand the criteria on which the ESG rating is based, which strengthens trust in the rating.[133] Last but not least, the AI analysis can be used to include those criteria in the calculation that have a real impact on sustainable development.[134]

By incorporating and analyzing data from internet of things technologies such as wearables or telematics technologies, insurance companies could set positive incentives for a more sustainable lifestyle, e. g. in the form of agreements with the policyholder. For example, if a policyholder walks to work or uses their bike instead of their car, they will not only improve their fitness, which can lead to lower incidence of illness and therefore lower costs for the insurer and the insurance community, but they will also make a positive contribution to the climate because emissions are saved by not using the vehicle.[135]

iv. Alternative measures

The alternative to AI-driven ESG research is the current ESG rating system, in which many different rating agencies attempt to analyze and evaluate the sustainable position of companies and financial products. The literature takes a positive view of ESG ratings for reasons of sustainability, because they translate the multitude of complex data into a rating that is easy to understand and comparable across the industry. At the same time, it satisfies the needs of investors who not only look at economic indicators when making their investment decision, but also want to make a contribution to a more sustainable world with their investment. This makes a positive ESG rating a competitive feature that encourages insurance companies to make the greatest possible sustainability efforts.[136] However, ESG ratings from conventional rating agencies have considerable disadvantages. The calculation basis for the ESG ratings is only transparent in very few cases, which is why it is very difficult for third parties to understand the basis on which the rating was calculated.[137] In addition, there are 30 to 40 rating agencies in the European Union alone, and each company is keen to include in its sustainability report those ratings that attest to a particularly positive result.[138] Inconsistencies within and between the rating agencies make comparability more difficult, which can be illustrated by a practical example: Both MSCI ESG and Sustainalytics are renowned rating agencies that specialize in the insurance and financial sector and whose ratings are reported by the majority of insurers and reinsurers in the sustainability report. The rating agency MSCI ESG rated the insurance company Axa as “AAA” in 2023[139] and Allianz as “AA”, which is lower.[140] Sustainalytics in turn gave Axa an ESG rating of 16.3 points in 2023,[141] while Allianz, with a lower score of 11.9 points, had a lower ESG risk.[142] A more impressive example that shows the inconsistency within a rating is that of Fresenius and Galp Energia in 2020. MSCI ESG rated Galp Energia, the largest Portuguese oil and gas company, with the best rating of “AAA”,[143]while the medical technology and healthcare group Fresenius was punished with the fourth worst rating of “BBB”, mainly due to a tax scandal.[144]

4. Drivers and barriers

In the previous chapters, the sustainability issues were identified and corresponding solutions that improve the sustainability of insurance and reinsurance companies as well as the insurance industry were discussed. In this chapter, the drivers and barriers of sustainability will be addressed. Within the sub-chapters “Drivers” and “Barriers”, a distinction is made between (i.) sector-specific drivers / barriers and (ii.) sector-specific company-internal drivers / barriers. The “Barriers” chapter also deals with best practice examples to overcome (iii.) firm external and (iv.) firm internal barriers.

4.1 Drivers

i. sector-specific drivers

The consistent implementation of green insurance elements can be seen as a driver in that an industry-wide transformation of the insurance and reinsurance sector not only reduces the emissions of its own sector, but also creates incentives that encourage private households and organizations in other sectors to also behave sustainably.[145] In the context of green insurance purchasing and product life cycle, the example of car insurance was used to show how insurance companies can influence policyholders and companies in other sectors through the design of car insurance. If, instead of economic indicators such as the comparison of the current value of the vehicle before damage occurs and the repair value, ESG indicators such as the comparison of environmental costs in emissions from a new vehicle purchase and a vehicle repair are also considered, then insurance companies will be more willing to pay the higher bill for a vehicle repair than to pay the lower current value of the car before damage occurs. Such a strategy would have direct consequences for the automotive industry, as the demand for new vehicles could decrease and car manufacturers would focus on the modularity of existing vehicle models instead of producing new vehicles, allowing car owners to upgrade their vehicles to the latest version. If this sustainability model becomes established in the insurance industry, this could lead to a sustainable change in other sectors, which could be reflected positively in global emissions, climate-related losses and, not least, in the claims balance of climate risk insurances.[146]

In addition, the insurance industry has created financial products that have been invested in recent decades in industries that have a significant share in man-made climate change as a result of pollution and emissions because they expected high returns in those industries. Although many insurance and reinsurance companies are now pursuing a divestment strategy from sectors such as the tobacco or nuclear weapons industry, the insurance industry has a responsibility for the damage caused by the sectors invested in.[147] It is therefore only logical, for ethical and social reasons, for the insurance industry to provide affordable microinsurance to those groups of people and organizations most affected by the consequences of man-made climate change. Such an approach would not show that the insurance industry is oriented towards sustainability, but has learned from its past mistakes.[148]

Last but not least, the third chapter addressed the high number of insurance fraud cases worldwide, which not only burdens the insurance industry, but in particular the insured community through higher insurance premiums. Existing software systems for fraud detection can be manipulated and are prone to errors. Human error due to incorrect entries in such systems can lead to unjustified disadvantages for people who can take out insurance. Tracking fraud cases using DLT/blockchain in conjunction with smart contratcs not only generates lower costs due to the potential for automation, but is also transparent and less prone to error for all parties involved. Such a tamper-proof system can help with claims settlement because the insurer can check on the temper-resistant blockchain whether a claim that has already been settled with another insurance company has also been resubmitted.[149]

ii. sector-specific company-internal drivers

An early green insurance orientation can be seen as a strategic competitive advantage, as consumer demand for sustainable products has risen sharply in recent years and consumers are increasingly opting for companies and products that are environmentally friendly. As first movers, green insurance companies cannot differentiate themselves from their competitors, but can define the market and its rules that will dominate in the foreseeable future.[150]

The chapter that dealt with big data and AI showed how companies can use internet of things technologies to create new data in order to define relevant risk characteristics for their insurance policies, which in turn can be used for pricing the insurance. The example of telematics technology was cited, among others, according to which the risk of a vehicle owner is measured not only by the kilometers driven but also by the driving style. Careful and unfriendly behavior could be rewarded with an insurance discount. At the same time, health insurers could reward their policyholders with discounts if they use their bicycles or walk instead of driving. In both cases, the insurance companies concerned benefit from a lower risk, while policyholders have to pay lower insurance premiums as a result of discounts. In the same breath, insurance companies receive new data on risk characteristics that have a significant impact on risk without including gender. By heterogenizing the pool of insured persons, negative effects such as adverse selection, which can harm all insured persons in a tariff, are eliminated.[151]

Last but not least, the literature emphasizes the long-term potential for innovation and cost optimization through the use of technologies such as DLT/blockchain and smart contracts[152] as well as big data and AI[153] for insurance companies.

4.2 Barriers

i. sector-specific barriers

The literature identifies barriers to both the concept of green insurance and the technologies that can be used to promote sustainability. Stricker et al. (2022) explain that the sustainability transformation is all-encompassing, complex and, in contrast to profit-oriented insurance companies, associated with greater hurdles, as breaking new ground can be risky and cost-intensive. In addition, the existing work to date does not have a ready-to-implement checklist, because research into the insurance industry is still basic research. It is therefore necessary for companies to formulate their own responses to sustainability issues, although this may be more difficult for smaller insurance companies due to limited company resources.[154]

The barriers to the technologies presented in this article, which can be used to improve sustainability, are particularly high. Anguiano and Parte (2023) list political, economic, social, environmental and legal barriers to the use of DLT/blockchain and smart contracts. For example, the discussion surrounding blockchain in politics is largely one-sided and mainly centered around Bitcoin. The blockchain is therefore seen as an instrument for alternative and uncontrollable payment transactions, without the full potential of the technology being appreciated. From an economic perspective, the implementation of such technologies could be associated with high one-off costs, which is a problem for small and medium-sized enterprises in particular.[155] Due to the cost factor, some insurers would adopt a “wait and see” position, in which they observe the usability of the technologies among competitors.[156] From an environmental perspective, blockchain is associated with high energy consumption,[157] disregarding the fact that eco-friendly DLT/blockchain solutions exist for this purpose.[158] From a social perspective, it is observed that blockchain technology is still considered risky. A lack of experience and the loss of personal data are cited as reasons for this.[159] In technological terms, the technologies mentioned are still in their infancy.[160] Technical standards must first be set so that these technologies can be adapted for use in the insurance industry.[161] From a legal perspective, the technologies are in a “legal vacuum”. Their use is still largely unregulated and therefore associated with uncertainties. At the same time, some aspects such as the collection of personal data are restricted, which could make it more difficult for insurance companies to use these technologies in practice.[162]

ii. sector-specific company-internal barriers

Anguiano and Parte (2023) explain that the implementation of new technologies is one of the most biggest difficulties, as it is associated with high switching costs and is time-consuming. In addition, it is often difficult in practice to find qualified personnel who are familiar with the technology.[163]

In the corporate context, the work of Francois and Voldoire (2023) is insightful. The two scientists investigated why telematics technology in conjunction with big data did not catch on in insurance companies, which they wanted to use for car insurance. It is interesting to note that policyholders were generally not averse to share their driving information. Moral or political reasons also did not contribute significantly to the failure of telematics. Instead, the authors observed that organizational and cognitive inertia had a significant contribution. The sales force, which was supposed to advise customers on telematics tariffs, was not always convinced by the technology. The authors report that there were salespeople who were able to advise on the tariffs out of conviction, and those salespeople who saw additional work in advising on the new tariffs and presenting the technology, but who were not compensated with a special commission. The formulated strategy was therefore simply not supported by all employees. This was also evident from the fact that there was no resistance among customers to installing telematics technology in the car, while employees rejected the installation of telematics devices in company vehicles because they feared that their bosses would track their driving routes.[164]

Furthermore, telematics devices make it theoretically possible to pay for your own individual risk. Considerate and prudent driving would be rewarded with a discount, while speeding would be penalized. In Francois and Voldoire’s experiment, the companies were unable to put this logic into practice. The data collected so far with the help of telematics was insufficient and poor to design a differentiated bonus-malus system. Some customers therefore stated that different driving styles did not affect the price. Overall, the technology was not implemented consistently, with the formulated strategy reaching its limits in practice. Organizational and cognitive resistance is therefore an important factor in the introduction of new technologies that are intended to improve the sustainability of an insurance company.[165]

iii. best practice to overcome firm external barriers

The challenges faced so far in implementing concrete measures to improve the insurance industry are due to a cautious “wait and see” approach.[166] Brophy (2019) proposes sandbox systems, i.e. secure environments in which insurance companies can test experimentally. Such sandbox tests could minimize or solve several external challenges at the same time.[167] DLT/blockchain, smart contracts and big data in conjunction with AI are still in their infancy in the insurance context.[168] Testing and learning with these technologies in a secure environment could identify potential weaknesses in the implementation of the technology and fuel its further development.[169] In contrast to the previous telematics example, companies would know which technological and organizational obstacles they would encounter. Initial test results in such sandboxes could also be used to convince stakeholders and policymakers of the benefits of the technology.[170] Above all, political decision-makers could weigh up the possibilities of technologies and the minimization of systemic risks,[171] which could prove difficult if the public debate on cryptocurrencies, as in the case of blockchain, is still predominantly cautious or mistrustful.[172] Sandbox tests are therefore not only a suitable way to explore the practical potential for the insurance industry, but also to accelerate the regulatory process.[173]

iv. best practice to overcome firm internal barriers

The insights of Francois and Voldoire (2023) have shown that cognitive and organizational inertia have sealed the failure of telematics in the companies studied. [174]

In their work, Stricker et al. (2023) have developed recommendations on how these obstacles can be overcome and sustainability can be established in insurance and reinsurance companies. They explain that there can be no obvious end point before the implementation of sustainable measures, so the strategy must be adapted to new findings. The strategy should therefore not be too rigid and allow the organization to be flexible. At the same time, it is not enough to simply pass on sustainability measures from the top down. The targets must be linked to management and individual incentives so that they are recognized throughout the company.[175] In the case of Francois and Voldoire, the telematics experiment was commanded downwards by management without the employees recognizing the added value of the technology for the company, which ultimately led to them perceiving the measure as an obstacle.[176] However, both clear tow-down leadership and local execution are needed. This can only be achieved if the sustainability strategy and its measures can be understood and accepted by the entire workforce. An open discourse for example in the form of regular workshops that takes into account the practical perspectives of employees and leads to a change in strategy is essential. Particularly in the context of sustainability, it is insufficient to think in terms of small organizational units such as departments. Company-wide and close collaboration between the departments and the service providers involved is necessary in order to avoid falling into frustration, resignation or cynicism.[177]

References

1 Oxford. Insurance. Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/insurance (2024).

2 Zweifel, P., Eisen, R. & Eckles, D. L. Insurance Economics (2nd Ed.). (Springer Switzerland, 2021).

3 Mannes, A. Insurance. in Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. (eds. Seligman, E. R. A. & Johnson, A.) 95-113 (Macmillan, 1932).

4 Hax, K. Grundlagen des Versicherungswesens. (Gabler, 1964).

5 Arrow, K. J. Aspects of the Theory of Risk-Bearing. (Yrjö Johnsson Lectures, 1965).

6 Zweifel, P., Eisen, R. & Eckles, D. L. Insurance Economics (2nd Ed.). (Springer Switzerland, 2021).

7 Landes, X. Insurance. in Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. (eds. Idowu, S. O., Capaldi, N. Zu, L. & Gupta, A. D.) 1433-1440 (Springer Germany, 2013).

8 Ibid.

9 Weber, C. Insurance Linked Securities. The Role of the Banks. (Springer Germany, 2011).

10 Ibid.

11 Mildenhall, S. J. & Major, J. A. Pricing Insurance Risk. Theory and Practice. (John Wiley & Sons, 2022).

12 Weber, C. Insurance Linked Securities. The Role of the Banks. (Springer Germany, 2011).

13 Rockoff, H. Introduction. in Role of Reinsurance in the World. Case Studies of Eight Countries. (eds. de las Cagigas, L. C. & Straus, A.) 1-12 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2021).

14 Kim, S. M. Payment Methods and Finance for International Trade. (Springer, 2021).

15 Deutsche Bank. Analyses of the importance of the insurance industry for financial stability. (2014).

16 Statista. Total investment portfolio value of insurers operating on the European market in 2020, by country. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/438182/investment-portfolio-of-insurers-country-europe/ (2022).

17 Handelsblatt. Allianz investiert eine Milliarde Euro in Glasfaser-Ausbau in Österreich. https://www.handelsblatt.com/finanzen/banken-versicherungen/versicherer/versicherer-allianz-investiert-eine-milliarde-euro-in-glasfaser-ausbau-in-oesterreich/27837622.html (2021).

18 Handelszeitung. Axa schafft grössten Immobilienfonds der Schweiz. https://www.handelszeitung.ch/insurance/axa-schafft-grossten-immobilienfonds-der-schweiz-661984 (2023).

19 European Central Bank. Financial Stability Report. The Importance of Insurance Companies for Financial Stability. (2009).

20 Zweifel, P., Eisen, R. & Eckles, D. L. Insurance Economics (2nd Ed.). (Springer Switzerland, 2021).

21 Lanfranchi, D. & Grassi, L. Examining insurance companies’ use of technology for innovation. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 47, 520-537 (2021).

22 Gualandri, E., Bongini, P., Pierigè, M. & Di Janni, M. (2024). Climate Risk and Financial Intermediaries. Regulatory Framework, Transmission Channels, Governance and Disclosure. (Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2024).

23 Diwekar, U. et al. A perspective on the role of uncertainty in sustainability science and engineering. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 164, 1-12 (2021).

24 Scholer, M. & Schuermans, P. (2022). Climate Change Adaption in Insurance. in Climate Adaption Modelling. (eds. Kondrup, C. et al.) 187-194 (Springer Switzerland, 2022).

25 Gatzert, N. & Osterrieder, K. The future of mobility and its impact on the automobile insurance industry. Risk Management and Insurance Review 23(1), 31-51 (2020).

26 Herrmann, A., Brenner, W. & Stadler, R. Autonomous Driving. How the Driverless Revolution Will Change the World. (Emerald Publishing, 2018).

27 Allianz. Allianz Real Estate, EDGE und BVK starten ein 1,3 Milliarden Euro schweres Programm zur Entwicklung intelligenter Büros. https://www.allianz.com/de/presse/news/geschaeftsfelder/immobilien/220310_Allianz-Real-Estate-EDGE-und-BVK-starten-Entwicklung-intelligenter-Bueros.html (2022).

28 Gatzert, N., Reichel, P. & Zitzmann, A. (2020). Sustainability risks & opportunities in the insurance industry. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Versicherungswirtschaft 109, 311-331 (2020).

29 Barrera, L. I. A. & Wagner, J. A systematic literature review on sustainability issues along the value chain in insurance companies and pension funds. European Actuarial Journal 13, 653-701 (2023).

30 Dathe, T., Helmold, M., Dathe, R. & Dathe, I. Implementing Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Principles for Sustainable Businesses. A Practical Guide in Sustainability Management. (Springer Switzerland, 2022).

31 Kirchhoff, K. R., Niefünd, S. & von Pressentin, J. A. (2024). ESG: Nachhaltigkeit als strategischer Erfolgsfaktor. SDG – Forschung, Konzepte, Lösungsansätze zur Nachhaltigkeit. (Springer Germany, 2024).

32 Tenuta, P. & Cambrea, D. R. Corporate Sustainability. Measurement, Reporting and Effects on Firm Performance. (Springer Switzerland, 2022).

33 Hielkema, P. Climate Change Insurance Needs. The EU and Global Sustainability Agenda for Finance. The EUROFI Magazine, 176 (2023).

34 Fung, T. C., Jeong, H. & Tzougas, G. Investigating the effect of climate-related hazards on claim frequency prediction in motor insurance, SSRN Papers, 1-20 (2023).

35 Gatzert, N., Reichel, P. & Zitzmann, A. (2020). Sustainability risks & opportunities in the insurance industry. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Versicherungswirtschaft 109, 311-331 (2020).

36 Swiss Re Institute (2022). A perfect storm. Natural catastrophes and inflation in 2022. https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sigma-research/sigma-2023-01.html (2023).

37 European Environment Agency (2022). Economic losses and fatalities from weather- and climate-related events in Europe. https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/economic-losses-and-fatalities-from (2022).

38 Swiss Re Institute (2022). A perfect storm. Natural catastrophes and inflation in 2022. https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sigma-research/sigma-2023-01.html (2023).

39 Tesselar, M., Botzen, W. J. W., Robinson, P. J., Aerts, J. C. J. H. Charity hazard and the flood insurance protection gap: An EU scale assessment under climate change. Ecological Economics 193(C), 1-23 (2022).

40 Barrera, L. I. A. & Wagner, J. A systematic literature review on sustainability issues along the value chain in insurance companies and pension funds. European Actuarial Journal 13, 653-701 (2023).

41 Elango, B., Chen, S. & Jones, J. Sticking to the social mission: Microinsurance in bottom of the pyramid markets. Journal of General Management 44(4), 189-242.

42 Swiss Re Institute (2022). A perfect storm. Natural catastrophes and inflation in 2022. https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/sigma-research/sigma-2023-01.html (2023).

43 Courbage, C. & Golnaraghi, M. Extreme events, climate risks and insurance. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 47, 1-4 (2022).

44 Schäfer, L., Warner, K. & Kreft, S. Exploring and Managing Adaption Frontiers with Climate Risk Insurance. In Climate Risk Management, Policy and Governance. Loss and Damage from the Climate Change. Concepts, Methods and Policy Options. (eds. Mechler, R. et al.) 317-342 (Springer Switzerland, 2019).

45 European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority. Policy measures to reduce climate-related insurance protection gaps. https://www.eiopa.europa.eu/publications/policy-measures-reduce-climate-related-insurance-protection-gaps_en (2023).

46 Courbage, C. & Golnaraghi, M. Extreme events, climate risks and insurance. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 47, 1-4 (2022).

47 Barrera, L. I. A. & Wagner, J. A systematic literature review on sustainability issues along the value chain in insurance companies and pension funds. European Actuarial Journal 13, 653-701 (2023).

48 Ibid.

49 Rempel, A. & Gupta, J. Conflicting commitments? Examining pension funds, fossil fuel assets and climate policy in the organisation for economic co-operation and development (OECD). Energy Research & Social Science 69, 1-9 (2020).

50 Alda, M. The environmental, social, and governance (ESG) dimension of firms in which social responsible investment (SRI) and conventional pension funds invest: The mainstream SRI and the ESG inclusion. Journal of Cleaner Productions 298, 1-11 (2021).

51 Nogueira, F. G., Lucena, A. F. P. & Nogueira, R. Sustainable insurance assessment: towards an integrative model. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 43(2), 275-299 (2018).

52 Gatzert, N. & Reichel, P. Sustainable investing in the US and European insurance industry: a text mining analysis. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance – Issues and Practice 49, 26-62 (2018).

53 Golnoraghi, M. Climate change and the insurance industry: taking action as risk managers and investors. Perspectives from C-level executives in the insurance industry. The Geneva Association. (2018).

54 Avramov, D., Cheng, S., Lioui, A. & Tarelli, A. Sustainable investing with ESG rating uncertainty. Journal of Financial Economics 145(2), 642-664 (2022).

55 Barber, B. M., Adair, M. & Yasuda, A. Impact Investing. Journal of Financial Economics 139(1), 162-185 (2021).

56 Gatzert, N., Reichel, P. & Zitzmann, A. (2020). Sustainability risks & opportunities in the insurance industry. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Versicherungswirtschaft 109, 311-331 (2020).

57 Allianz. Building confidence in tomorrow. Sustainability Report 2022. (2023).

58 Ibid.