Authors: Paula Fuhr, Larissa Sophie Nöthel, Juliane Pieper, Aylin Christin Schindler

Edited by: Tom Glaeseker, Jens Holzkämper, Luca Thost, Tammo Resener

Last updated: December 29, 2022

1 Definitions

1.1 Supply chain management

In simplified terms, supply chain management (SCM) can be described as a process in which three or more entities (organizations or individuals) are directly involved in an upstream and downstream flow of products, services, finances, or information from a source to a customer. The process usually starts with unprocessed raw materials and ends with the finished product at the end customer.1 Mentzer, J. T., DeWitt, W., Keebler, J. S., Min, S., Nix, N. W., Smith, C. D., & Zacharia, Z. G. (2001). DEFINING SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT. Journal of Business Logistics, 22(2), 1–25. As defined by the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals (CSCMP) supply chain management encompasses the management of all activities involved in sourcing and procurement and all other logistics management activities. The coordination with supply chain partners is an essential part of this. Thus, supply chain management links supply and demand management across companies and includes manufacturing operations, marketing, sales, product design, finance, and information technology.2 CSCMP (2013). CSCMP Supply Chain Management Definitions and Glossary. Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx

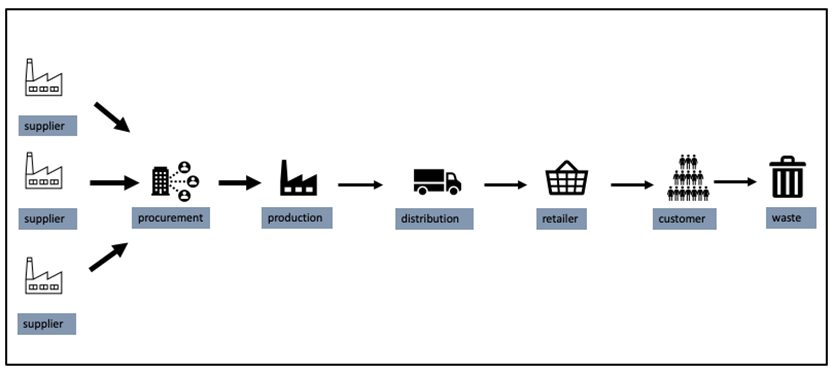

Figure 1 shows a classic and simplified supply chain process, which is typical for manufacturing industries. The process begins with the purchase of materials from suppliers. The materials obtained from the procurement firm are processed into the final product through production and are then distributed or stored. Through distribution, they usually first reach a seller and then the customer. Finally, most products end up as waste at the end of use.3 Hofmann, S. (2020). Was ist Supply Chain Management? Definition, Beispiel & Ziele. MM Logistik. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.mm-logistik.vogel.de/was-ist-supply-chain-management-definition-beispiel-ziele-a-614558/

Source: Own illustration based on Hoffmann (2020)3 Hofmann, S. (2020). Was ist Supply Chain Management? Definition, Beispiel & Ziele. MM Logistik. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.mm-logistik.vogel.de/was-ist-supply-chain-management-definition-beispiel-ziele-a-614558/ .

1.2 Sustainable supply chain

Since supply chains are the origin of a large share of environmental and social impacts of firms, they also hold a great potential to avoid or minimize these risks. As an insufficient supplier management can lead to catastrophes. As the collapse of the Rana Plaza Building in Bangladesh revealed, it is important to address social and environmental issues along the supply chain.4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf

A classical definition of sustainable supply chain management (SSCM) is given by Seuring and Müller (2008) who defined SSCM as “The management of material, information and capital flows as well as cooperation among companies along the supply chain while taking goals from all three dimensions of sustainable development, i.e. economic, environmental and social, into account which are derived from customer and stakeholder requirements.”5 Page 1700: Seuring, S., & Müller, M. (2008). From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. Journal of Cleaner Production, 16(15), 1699–1710. SSCM therefore involves integrating environmentally friendly practices in a holistic way into the supply chain lifecycle. Beginning with raw material selection and sustainable production the stream continuous with green packaging and transportation, warehousing, distribution and lastly consumption, return and disposal.6 Sustainable Supply Chain Foundation (o. D.). What is sustainable supply chain management?. Sustainable Supply Chain Foundation. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: http://www.sustainable-scf.org/ Only looking at the use phase of a product is insufficient, SSCM addresses both the history and the future. Impacts during different life stages of the product (e.g., resource use during production, toxic effects) are included.7 Carter, C. R., & Rogers, D. S. (2008). A framework of sustainable supply chain management: moving toward new theory. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 38(5), 360–387.

The non-sustainability of a focal firm is linked not only to environmental issues that arise in the supply chain but also to social issues. The focal firm is the most powerful firm in control of most of the supply chain or the firm whose perspective is adopted.8 Masi, D., Kumar, V., Garza-Reyes, J. A., & Godsell, J. (2018). Towards a more circular economy: exploring the awareness, practices, and barriers from a focal firm perspective. Production Planning & Control, 29(6), 539–550.

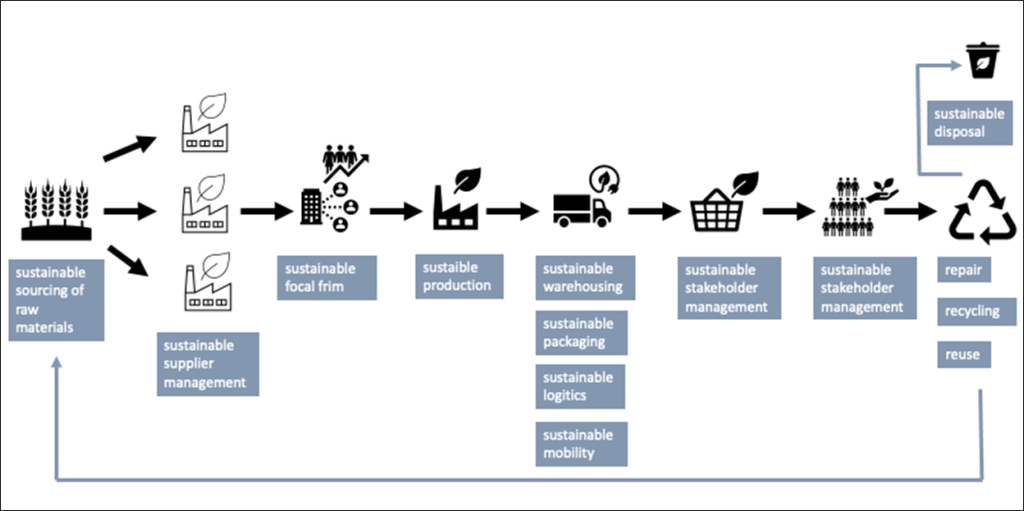

Figure 2 shows a simplified sustainable supply chain. It starts with the sustainable sourcing of raw materials and a sustainable supplier management. These materials are obtained by the focal firm which is in charge of sustainable production. This is followed by sustainable distribution, which includes sustainable warehousing, sustainable packaging, sustainable logistics and mobility. Hereafter comes sustainable stakeholder management with retailers and customers. At the product’s end a sustainable disposal must be taken care of or even better the product can be repaired, recycled or reused.9 Schandl H., King S., Walton A., Kaksonen A., Tapsuwan S., & Baynes, T. (2020). National circular economy roadmap for plastics, glass, paper and tyres. CSIRO, Australia.

Retrieved on 18.08.21: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349413852_National_circular_economy_roadmap_for_plastics_glass_paper_and_tyres

Source: Own illustration based on Schandel et al. (2020)9 Schandl H., King S., Walton A., Kaksonen A., Tapsuwan S., & Baynes, T. (2020). National circular economy roadmap for plastics, glass, paper and tyres. CSIRO, Australia.

Retrieved on 18.08.21: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/349413852_National_circular_economy_roadmap_for_plastics_glass_paper_and_tyres

Beyond reducing their overall carbon footprint, there are many reasons why organizations should address sustainability in their supply chains. Different priorities can be addressed e.g., environmental stewardship, conservation of resources, financial savings and viability or social responsibility.6 Sustainable Supply Chain Foundation (o. D.). What is sustainable supply chain management?. Sustainable Supply Chain Foundation. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: http://www.sustainable-scf.org/

2 Impact of sustainability and sustainable performance indicators in SSCM

2.1 Importance of measuring sustainability in SSCM

Sustainability refers to the activities of companies to implement sustainable as well as socio-ecological requirements along the entire value chain.10 Arnold, M. (2017). Fostering sustainability by linking co-creation and relationship management concepts. Journal of Cleaner Production, 140(1), 179–188. Thus, sustainable supply chains are an essential part of a sustainable development. The growing importance for sustainable supply chains is driven by environmental degradation, such as depleting raw material resources, overflowing landfills and rising pollution.11 Kumar, R., & Chandrakar, R. (2012). Overview of green supply chain management: Operation and environmental impact at different stages of the supply chain. International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 1(3), 1–6. The pollution and emissions caused by supply chain activities contribute significantly to serious environmental problems, resulting in global warming.12 Hassini, E., Surti, C., & Searcy, C. (2012). A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. International Journal of Production Economics, 140, 69–82. However, also substantial social problems arise in relation to supply chain activities such as human rights violations and forced child labour. Changes due to globalization and increasing uncertainty as well as the growing awareness of customers and pressure from regulatory authorities and NGOs are just some of the factors influencing this issue.12 Hassini, E., Surti, C., & Searcy, C. (2012). A literature review and a case study of sustainable supply chains with a focus on metrics. International Journal of Production Economics, 140, 69–82.

With a sustainable supply chain, companies can show their stakeholders that they are aware of their responsibilities and prepared to actively address and counteract substantial sustainability impacts and risks as far as possible.4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf However, companies can only be sustainable if sustainability issues are addressed at every level of their supply chain.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19. 14 Taticchi, P., Tonelli, F., & Pasqualino, R. (2013). Performance measurement of sustainable supply chains. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62(8), 782–804. Nevertheless every step towards a more sustainable supply chain is significant. A sustainable approach helps a company to maintain its profitability while at the same time fulfilling its responsibility to protect human rights and thereby fulfilling its social responsibility.15 Ansari, Z. N., & Qureshi, M. N. (2015). Sustainability in supply chain management: An overview. IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, 12(2), 24–46.

Improving organizational sustainability is a long-term process that requires internal, social, and environmental efforts.14 Taticchi, P., Tonelli, F., & Pasqualino, R. (2013). Performance measurement of sustainable supply chains. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62(8), 782–804. This is where the importance of sustainable performance indicators and their measurement becomes apparent. The measurement of such indicators often serves as an assessment to initiate improvements and to raise awareness about the extent of sustainability issues within the supply chain. Thereby SSCM must meet not only several but conflicting objectives simultaneously, such as maximizing revenue while reducing operating costs.14 Taticchi, P., Tonelli, F., & Pasqualino, R. (2013). Performance measurement of sustainable supply chains. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62(8), 782–804. However, if companies design their own processes in a sustainable way, significant cost savings for instance in resource, energy, and transport costs can be achieved. With increasingly efficient processes and systems, the need for other resources falls and so do e.g., manufacturing costs.4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf

2.2 Sustainable performance indicators for measuring sustainability in SSCM

Sustainability performance indicators (SPIs) are supposed to help companies to measure their performance at least in one of the three dimensions of social, ecological, and economic sustainability, according to the triple bottom line (TBL) approach.13

Looking at the various guidelines and standards that have been published in recent years, it can be difficult for companies to get an overview of the latest developments in sustainability measurement. For example, one of the leading retail and tourism groups in Europe the REWE Group, for example, has a highly ranked sustainability report which uses various GRI guidelines as a reference for its SSCM measurements.16 IÖW (2018). Ergebnisliste – Ranking der Nachhaltigkeitsberichte 2018. Retrieved on 01.08.2021: https://www.ranking-nachhaltigkeitsberichte.de/fileadmin/ranking/user_upload/2018/Ranking_Nachhaltigkeitsberichte_2018-Ergebnisliste.pdf 16 REWE Group (2019). Sustainability Report 2019. Retrieved on 01.08.2021: https://rewe-group-nachhaltigkeitsbericht.de/2019/en/index.html Although REWE Group has focused on one guideline, there are others that can be considered to track sustainability metrics. The literature lacks an overarching, standardized methodology as well as transparency, as there is much conflicting information on sustainability performance.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19. Therefore, a paper by Saeed and Kersten (2017) published in the German Logistics Association BVL aims to provide such an overarching best practice methodology to help companies to understand, measure, and track important SPIs of their supply chain. This is of importance as measuring and managing performance requires the establishment of goals against which the achievement can be measured.17 Schaltegger, S., & Burritt, R. (2014). Measuring and managing sustainability performance of supply chains. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 19(3), 232–241. For this approach, the authors analyzed the following 12 international guidelines and standards, which provide metrics for assessing supply chain performance in the three sustainability dimensions13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19. :

| EMAS18 EMAS (2009). Eco-management and audit scheme. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2009/1221/oj.. | SCOR19 SCOR (2012). Supply chain operations reference model: supply chain council, United States of America (11.0). Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://docs.huihoo.com/scm/supply-chain-operations-reference-model-r11.0.pdf | GRI20 GRI (2013). Sustainability reporting guidelines. Global reporting initiative. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ | IChemE21 IChemE (2002). The sustainability metrics: Sustainable development progress metrics recommended for use in the process industries. Institution of chemical engineers. Retrieved on 02.08.2021: https://www.greenbiz.com/sites/default/files/document/O16F26202.pdf | ILO22 ILO (2014). International labour standards by subject. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: http://www.ilo.org/global/standards/subjects-covered-by-international-labour-standards/WCMS_230305/lang–en/index.htm | ISO 1400123 ISO 14001 (2015). Environmental management systems – Requirements with guidance for use. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:14001:ed-3:v1:en |

| ISO 1403124 ISO 14031 (2013). Environmental management – Environmental performance evalua-tion – Guidelines. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:14031:ed-2:v1:en | ISO 2600025 ISO 26000 (2010). Guidance on social responsibility. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:26000:ed-1:v1:en | OECD26 OECD (2011). OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, 2011 Edition. Retrieved on 02.08.2021: https://www.oecd.org/investment/mne/48004323.pdf https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264115415-en | OHSAS 1800127 OHSAS (2019). Occupational health and safety management systems. In T. P. Fuller (Ed.), Global occupational safety and health management handbook (1st ed., pp. 79–93). Florida, FL: CRC Press. | SA800028 Social accountability 8000 (2014). Social accountability 8000: International standard (sa 8000). Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://sa-intl.org/programs/sa8000/ | UNGC29 United Nations Global Compact, BSR (2015). Supply chain sustainability a practical guide for continous improvement, second edition. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://d306pr3pise04h.cloudfront.net/docs/issues_doc%2Fsupply_chain%2FSupplyChainRep_spread.pdf |

To manage and track the sustainability performance, a set of sustainability goals represented by the following categories should be achieved by SSCM.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19.

2.2.1 Sustainable performance indicators for environmental sustainability

Regarding environmental sustainability, i.e. the use of resources by preserving the natural regenerative capacity, the performance indicators are divided into the following subcategories30 Elkington, J. (1998). Accounting for the triple bottom line. Measuring Business Excellence, 2(3), 18–22. defined in this section. Energy efficiency classifies total energy consumption from both renewable and non-renewable energy sources. Material efficiency refers to total material consumption as well as the use of renewable, hazardous, and recycled materials. Water management addresses all forms of water consumption as well as total water discharge and the quality of water discharge. Waste management classifies all forms of waste produced and recycled. Emissions include direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions, ozone depleting substances, VOCs, NOx, SOx, and particulate matter. Land use represents the total area used for an organization’s operations. Whereas environmental compliance to environmental regulations refers. Finally, supplier assessment considers the environmental performance of suppliers and their selection criteria.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19.

| # | Indicator | SPI |

| 1 | Energy Efficiency | 1-2) Total and specific annual energy consumption 3) Total annual renewable energy consumption |

| 2 | Material Efficiency | 1-2) Total and specific annual material consumption 3) Total annual renewable material consumption 4) Total annual recycled/reused material consumption 5) Total annual hazardous materials consumption 6) Specific annual hazardous materials consumption |

| 3 | Water Management | 1-2) Total and specific annual volume of water consumption 3) Total annual volume of water recycled/reused 4) Percentage of annual volume of water recycled/reused 5) Total annual volume of wastewater discharged 6) Specific annual volume wastewater discharge |

| 4 | Waste Management | 1-2) Total and specific annual amount of waste generated 3-4) Total and specific annual amount of hazardous waste generated 5) Specific annual amount of waste recycled/reused 6) Percentage of waste recycled/reused |

| 5 | Emissions | 1) Total annual amount of direct GHGs (CO2, CH4, N2O, HFCs, PFCs, SF6, NF3) emissions (Scope-1) 2) Total annual amount of indirect GHGs (Scope-2) 3) Total annual amount of other GHGs (Scope-3) 4) Specific annual GHGs emissions (Scope-1&Scope-2) 5-6) Total and specific annual amount of ozone-depleting substances 7) Total annual amount of particulate matter emissions 8) Total annual air emission |

| 6 | Land use | 1-2) Total and specific size of the operational site/facility |

| 7 | Environmental compliance | 1) Total annual number of non-compliance with environmental regulations |

| 8 | Supplier assessment | 1) Percentage of supplier’s subject to sustainability assessment 2) Percentage of local/national/provincial suppliers |

2.2.2 Sustainable performance indicators for social sustainability

The SPIs in the social dimension of sustainability, which considers a company’s responsibility management towards its social and human capital, include the following categories30 Elkington, J. (1998). Accounting for the triple bottom line. Measuring Business Excellence, 2(3), 18–22. : Human rights and anti-corruption, which addresses all forms of corruption and the violation of basic human rights. The HR indicator addresses all forms of human resource management. To cover the health and safety of all employees, its indicator collects information on occupational health and safety issues. The training and development indicator addresses the training and development opportunities available to employees. Consumer issues such as complaints, product returns, etc. are also captured. Finally, compliance with social regulations is measured.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19.

| # | Indicator | SPI |

| 9 | Human rights and anti-corruption | Total annual number of: 1) incidents of discrimination 2) incidents where the right to freedom of association and the effective recognition of the collective bargaining are violated 3) incidents of forced labor 4) incidents of child labor 5) incidents of corruption |

| 10 | Human resource | Total annual number of: 1) employees; 2) female employees; 3) new male employees; 4) new female employees; 5) male employees from the region; 6) female employees from the region; 7) male employees’ turnover; 8) females employees’ turnover; 9) employees entitled to life insurance, healthcare, parental leaves, dividend, retirement provision, bonuses, injury payments, etc.; 10) employees receiving annual performance reviews |

| 11 | Health and safety | Total annual number of: 1) non-fatal occupational health and safety related accidents occurring int the course of work 2) days lost due to occupational health and safety related accidents 3) fatalities due to occupational health and safety related accidents |

| 12 | Training and education | Average hours of: 1) training per employee 2) training for female employees 3) training for male employees Total number of: 4) employees given training |

| 13 | Consumer issues | Total annual number of: 1) incidents of consumer complaints 2) incidents of engaging in misleading, deceptive, fraudulent of unfair practice 3) products returns (reclaimed products) |

| 14 | Social compliance | 1)Total amount of non-compliance with social criteria or regulations |

2.2.3 Sustainable performance indicators for economic sustainability

The third pillar of the TBL approach is economic sustainability which describes the distribution, flow and impacts of an organizations’ financial resources on the environment and society.30 Elkington, J. (1998). Accounting for the triple bottom line. Measuring Business Excellence, 2(3), 18–22. It is measured by the following SPIs: First, stability and profitability illustrate the financial health of a company. Income distribution includes salaries and benefits for employees as well as payments to the state and local authorities. Market competitiveness measures an organization’s environmental performance relative to its competitors in the same market. And an organization’s economic performance relative to sustainability spending is measured by the last set of SPIs.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19.

| # | Indicator | SPI |

| 15 | Stability and profitability | 1) Total annual sales/revenues 2) Operating profit 3) Free cash flow 4) Total number of products produced |

| 16 | Income distribution | Total annual: 1) number of wages and benefits given to employees by an organization 2) payments made to the Government (taxes) 3) amount of community investment 4) operating cost |

| 17 | Market competitiveness | Ratio of entry-level wage given to: 1) male employees in an organization to the minimum wage in a specific country or industry 2) female employees in an organization to the minimum wage in a specific country or industry |

| 18 | Sustainability expenditures | 1) Percentage of procurement budget spent on local suppliers 2) Total annual sustainability expenditures 3) Total research and development expenditure |

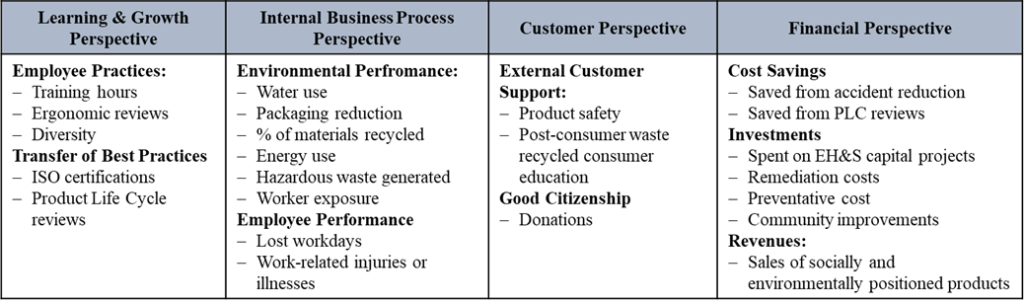

The SPIs can be arranged in sustainability-focused performance measurement systems, whose key priority is to track, communicate and significantly reduce the absolute level of negative ecological and social impacts and thus to contribute to a sustainability transformation of both markets and society.20 GRI (2013). Sustainability reporting guidelines. Global reporting initiative. Retrieved on 03.08.2021: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/ One possible instrument to visualize this performance measurements is the Sustainability Balanced Scorecard (SBSC). It aims to improve corporate performance in all three sustainability dimensions and thus achieve strong corporate sustainability contributions.31 Figge, F., Hahn, T., Schaltegger, S., & Wagner, M. (2001). Sustainability Balanced Scorecard. Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. Lüneburg, Germany: Centre for Sustainability Management e.V.

2.3 Advantages and disadvantages

There is a vital need for a multidisciplinary and balanced approach to performance measurement for supply chains.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19. 15 Ansari, Z. N., & Qureshi, M. N. (2015). Sustainability in supply chain management: An overview. IUP Journal of Supply Chain Management, 12(2), 24–46. This need for SPIs also brings many advantages. In general, indicators have a meaning that goes beyond the value of the parameter and thus provide significance and concentrated information that would otherwise require a larger amount of detailed information.32 Farsari, Y., & Prastacos, P. (2002). Sustainable development indicators: An overview. Crete, GR: Hellas – Foundation for the Research and Technology. Retrieved on 28.08.2021: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.196.4417&rep=rep1&type=pdf 33 Hardi, P., Barg, S., Hodge, T., & Pinter, L. (1997). Measuring sustainable development: Review of current practice. Occasional Paper Number 17. Winnipeg, Canada: International Institute for Sustainable Development. SPIs help organizations to assess and monitor their sustainability performance, while supporting them in communicating and implementing strategies at the operational and strategic levels.34 Agami, N., Saleh, M., & Rasmy, M. (2012). Supply chain performance measurement approaches: Review and classification. The Journal of Organizational Management Studies, 2012, 1–20. However, compliance with such standards is not only important in internal communication, but can also be a prerequisite factor when collaborating with other companies. For example, Google expects its suppliers to make essential commitments. If Google, one of the world’s largest tech companies, requires additional certifications such as ISO14001 or OHSAS 18001, suppliers must obtain these standards in a timely manner.35 Google LLC (n.d.). Verhaltenskodex für Lieferanten. Retrieved on 13.08.2021: https://about.google/supplier-code-of-conduct/ Another advantage of indicators is the comparability and reproducibility of the data.32 Farsari, Y., & Prastacos, P. (2002). Sustainable development indicators: An overview. Crete, GR: Hellas – Foundation for the Research and Technology. Retrieved on 28.08.2021: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.196.4417&rep=rep1&type=pdf This performance measurement system should also enable companies to evaluate or compare their sustainability performance. With the right set of SPI’s and continuous monitoring, companies benefit from a supply chain-wide competitive advantage.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19.

Besides these advantages, disadvantages or rather challenges of sustainability measurement can also be identified. Since both the environment and supply chains are made up of massive subsystems as well as huge processes, this makes managing their performance fairly complex in general. This complexity in global supply chains means that supplier quality improvement efforts are typically unobservable, making it difficult to measure these SPIs.36 Abbasi, M., & Nilsson, F. (2012). Themes and challenges in making supply chains environmentally sustainable. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 17(5), 517–530. 37 Cui, Y., Hu, M., & Liu, J. (2019). Values of Traceability in Supply Chains. Retrieved on 13.08.2021: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3291661 Choosing the right and appropriate SPIs to measure sustainability is also a major challenge. A disadvantage is the potential lack of appropriate data, which can lead to the absence of important information.32 Farsari, Y., & Prastacos, P. (2002). Sustainable development indicators: An overview. Crete, GR: Hellas – Foundation for the Research and Technology. Retrieved on 28.08.2021: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.196.4417&rep=rep1&type=pdf If the wrong measures are chosen, companies can be misguided and thus act less sustainably than expected.13 Saeed, M. A., & Kersten, W. (2017). Supply chain sustainability performance indicators – a content analysis based on published standards and guidelines. Logistics Research, 10(1), 1–19.

3 Functions and processes of SSCM

3.1 Sustainable supply chain risk-management

Sustainable supply chain risk management (SSCRM) refers to activities that aim to address and manage a focal firm’s exposure to sustainability-related supply chain risk sources.38 Hofmann, H., Busse, C., Bode, C., & Henke, M. (2013). Sustainability-Related Supply Chain Risks: Conceptualization and Management. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(3), 160-172. Principally, complex, and multilevel supply chains tend to lack traceability and thus trans-parency, which increases their risk for sustainability-related supply chain issues.4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf Figure 3 shows a selection of industry-dependent sustainability-related supply chain issues.

Source: Based on BMUB (2017)4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf

While ordinary supply chain risks are triggered by a disruption that disturbs the flow of goods, financial resources, or services, sustainability-related risks materialize through adverse stakeholder reactions to a sustainability-related triggering event in or close to the supply chain. Both lead to damaging consequences for the focal firm. Hence, SSCRM must consider both triggering mechanisms: disruptions and stakeholder reactions. Therefore, examining the supply network for sustainability issues that could provoke stakeholder reactions is important to attain and preserve stakeholder legitimacy and is thus a precondition for successful SSCRM. The stakeholders to be considered, include suppliers, local communities, governments, investors, shareholders, NGOs, the media, customers, and employees.38 Hofmann, H., Busse, C., Bode, C., & Henke, M. (2013). Sustainability-Related Supply Chain Risks: Conceptualization and Management. Business Strategy and the Environment, 23(3), 160-172.

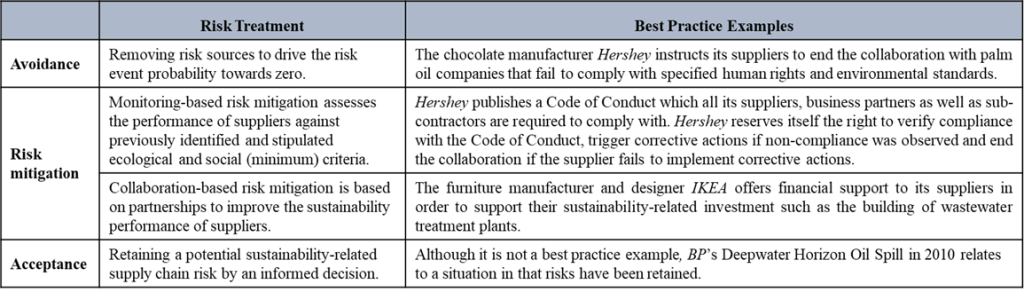

The ISO 31000 standard provides a methodology for companies to managing risks that is also applicable to address supply chain risks.39 ISO 31000 (2018), Risk management – Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en The first stage of the risk assessment is the identification of all potential sustainability-related supply chain risks.39 ISO 31000 (2018), Risk management – Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en 40 Giannakis, M., & Papadopoulos, T. (2016). Supply chain sustainability: A risk manage-ment approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 455-470. Mapping and visualizing the supply chain helps to create transparency and can serve companies as a starting point for this step.4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf A pragmatic example is displayed by the computer mice manufacturer Nager IT on its website.41 Nager IT. Our Supply Chain. Retrieved on 18.08.2021: https://www.nager-it.de/static/pdf/en_lieferkette.pdf Furthermore, conducting a life cycle assessment of a product allows a company to identify ‘hotspots’ of environmental impacts along its supply chain. ISO 14040 as well as ISO 14044 provide an approach for life cycle assessments.4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf The risk analysis aims to comprehend the nature of risk and asses their likelihood of occurrence and the magnitude of their potential impact on the supply chain performance.39 ISO 31000 (2018), Risk management – Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en To identify potential causes and consequences tools as root cause and sensitivity analyses or cause and effect analyses can be conducted.40 H Giannakis, M., & Papadopoulos, T. (2016). Supply chain sustainability: A risk management approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 455-470. The risk evaluation prioritizes the risk according to their relative importance to determine where additional action is required.39 ISO 31000 (2018), Risk management – Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en 40 H Giannakis, M., & Papadopoulos, T. (2016). Supply chain sustainability: A risk manage-ment approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 455-470. A materiality analysis geared towards the supply chain can support this step by assessing the magnitude of potential impacts on the company itself and on its stakeholders.4 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Building and Nuclear Safety (BMUB) Public Relations Division. (2017). Step-by-Step Guide to Sustainable Supply Chain Management. BMUB. Retrieved on 16.08.2021: https://www.bmu.de/fileadmin/Daten_BMU/Pools/Broschueren/nachhaltige_lieferkette_en_bf.pdf After the risk assessment is completed the risk treatment follows.39 ISO 31000 (2018), Risk management – Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en 40 H Giannakis, M., & Papadopoulos, T. (2016). Supply chain sustainability: A risk management approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 455-470. Four major responses exist to treat sustainability-related supply chain risks, which are explained and illustrated by best practice examples in table 5.42 Hajmohammad, S., & Vachon, S. (2015). Mitigation, Avoidance, or Acceptance? Managing Supplier Sustainability Risk. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 52(2), 48-65.

The effectiveness of the treatment strategies as well as changes in the dynamic nature of a supply chain or changes in regulations and policies should continuously be reviewed and monitored.39 ISO 31000 (2018), Risk management – Guidelines. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui#iso:std:iso:31000:ed-2:v1:en 40 H Giannakis, M., & Papadopoulos, T. (2016). Supply chain sustainability: A risk management approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 171, 455-470. Sustainable supply chain risk management and especially risk treatment strategies are closely linked to Sustainable Supplier Management.

3.2 Sustainable supplier management

Sustainable supplier management refers to the “management of all activities along the upstream supply chain related to the purchased component to maximize the triple bottom line performance.”45 Zimmer, K., Fröhling, M., & Schultmann, F. (2016). Sustainable supplier management – a review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development. International Journal of Production Research, 54(5), 1412-1442. This process is important, since the quality of a finished product is to a certain extent already determined through the materials delivered by suppliers, which also holds for sustainable aspects of a product throughout its life cycle.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Within sustainable supplier management the sustainable supplier selection, development, and monitoring are the typical independent but interrelated core processes.45 Zimmer, K., Fröhling, M., & Schultmann, F. (2016). Sustainable supplier management – a review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development. International Journal of Production Research, 54(5), 1412-1442.

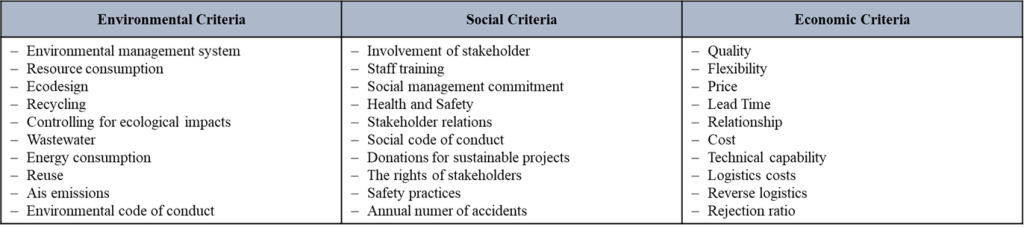

The sustainable supplier selection process usually starts with the identification of needs and specifications, based on which, criteria for the evaluation of suppliers are formulated.45 Zimmer, K., Fröhling, M., & Schultmann, F. (2016). Sustainable supplier management – a review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development. International Journal of Production Research, 54(5), 1412-1442. Sustainability performance can be improved at this stage by leveraging the integration of criteria that evaluate potential suppliers with regard to the TBL.45 Zimmer, K., Fröhling, M., & Schultmann, F. (2016). Sustainable supplier management – a review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development. International Journal of Production Research, 54(5), 1412-1442. Table 6 lists a selection of those criteria:

Beyond that, certification with social and environmental standards, such as ISO 14000 and ISO 50001, EMAS, SA 8000, as well as OHSAS 18001 are reasonable indicators to evaluate potential suppliers.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. After a first qualification round a final selection among those qualified suppliers takes place.

Over the lifetime of a contract, the actual performance of the supplier is monitored and evaluated based on the compliance with the predefined minimum criteria and previously stipulated performance improvements (sustainable supplier monitoring). The monitoring process aims to identify areas that require improvement and can thus serve as a trigger for supplier development activities or supplier replacement, but it also aims to reward good practices (sustainable supplier development).45 Zimmer, K., Fröhling, M., & Schultmann, F. (2016). Sustainable supplier management – a review of models supporting sustainable supplier selection, monitoring and development. International Journal of Production Research, 54(5), 1412-1442. 46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. For the purpose of monitoring and developing suppliers, certain tools and methods can be applied such as a Sustainable Supplier-Balanced Scorecard (an example is shown in Table 7), supplier visits and audits, supplier workshops and conferences as well as supplier sustainability trainings.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 47 Epstein, M. J., & Wisner, P. S. (2001). Using a Balanced Scorecard to Implement Sustainability. Environmental Quality Management, 11(2), 1-10.

The vendor management of the sports apparel producer Vaude follows the four steps of Sustainable Supplier Management. Among other things, Vaude has developed a special tool that includes international standards as well as local laws for their “performance check” (supplier selection). For the phase of the supplier development Vaude conducts on site trainings, in addition they have created a platform to exchange best practices, expert lectures, and workshops with and among their suppliers, called the VAUDE Vendor Club.48 Vaude (2021). Nachhaltigkeitsbericht. Retrieved on 28/07/2021: https://nachhaltigkeitsbericht.vaude.com/gri/vaude/unsere-lieferkette.php

The FSC certification system can be mentioned for this purpose. FSC stands for Forest Stewardship Council and serves as proof of sustainable forestry or plantations. Wood is needed in many areas nowadays, for books, toys or furniture. Therefore, wood suppliers are an integral part of many supply chains. The non-governmental organization was founded in 1993 and represents the interests of all forest stakeholders. FSC sets strict social and ecological guidelines on how forests may be harvested and managed. The aim is to preserve and develop forests in the long term.49World Wildlife Fund (n.d.). FSC – was ist das?. Retrieved on 15/09/2022: https://www.wwf.de/themen-projekte/waelder/verantwortungsvollere-waldnutzung/fsc-was-ist-das.

There are 1,162 members from 89 countries worldwide. In total, there are 216,294,553 FSC certified hectares. The continents of Africa and Asia account for the smallest share. North America and Europe have the largest contributions. In the context of the sustainable supply chain, it therefore makes sense to choose certified suppliers and producers. In the context of timber and forest harvesting, the FSC certificate, a globally recognized and common certification, is one way of selecting suppliers.50Forest Stewardship Council (n.d.). Facts & Figures. Retrieved on 15/09/2022: https://connect.fsc.org/impact/facts-figures.

3.3 Sustainable production

Main article: Sustainable production & manufacturing

Sustainable Production is defined as the “creation of goods and services using processes and systems that are non-polluting, conserving of energy and natural resources, economically viable, safe and healthful for employees, communities and consumers, and socially and creatively rewarding for all working people”.] Tools, such as Six Sigma, Value Stream Mapping, Life Cycle Assessment and End-of-Pipe-Technologies along with approaches such as Cradle-to-Cradle or Design for Environment help to lever sustainability in production.51 Veleva, V., & Ellenbecker, M. (2001). Indicators of sustainable production: Frameworks and methodology. Journal of Cleaner Production, 9, 519-549.

3.4 Sustainable logistics management (physical distribution and packaging)

Logistics management refers to the planning, implementation and controlling of the forward and reverse flow and storage of goods, including services and related information between the point of origin and the point of consumption to meet customer requirements.52 CSCMP (2013). CSCMP Supply Chain Management Definitions and Glossary. Retrieved on 04.08.2021: https://cscmp.org/CSCMP/Educate/SCM_Definitions_and_Glossary_of_Terms.aspx The main functions in logistics management are transportation and storage, although packaging is usually included as well, due to its function of making goods transportable and storable through logistics unit formation.53 Deckert, C. (2016). Nachhaltige Logistik. In C. Deckert (Ed.), CSR und Logistik (1st ed., pp.3-41). Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer Gabler. Sustainable logistics management (SLM) aims to fulfill these market demands while being as sustainable as possible in order to improve the supply chain sustainability in the logistics system.54 Soysal, M., & Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M. (2017). Toward Sustainable Logistics. In D. Cinar, K. Gakis, & P. M. Pardalos (Eds.), Sustainable Logistics and Transportation Optimization Models and Algorithms (1st ed., pp. 1-21). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

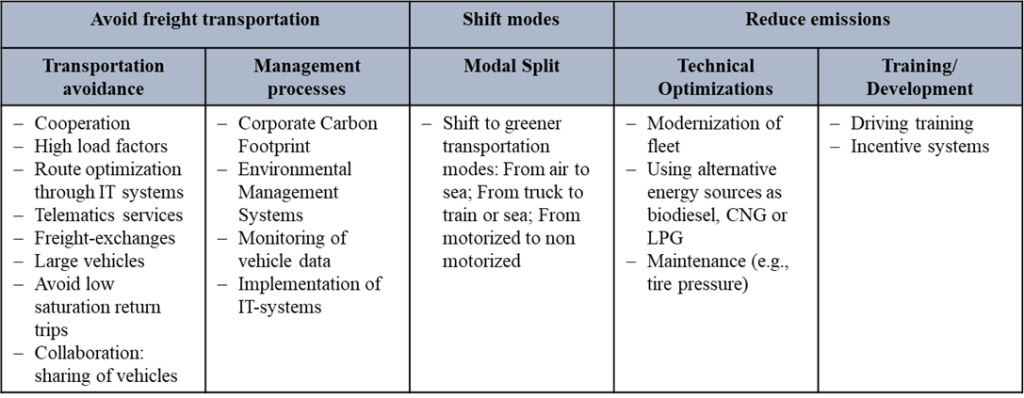

The application of three principles leverages the sustainability performance of freight transportation: avoid freight transportation, shift to more sustainable transportation modes, and reduce emissions.55 Schulte, C. (2016). Logistik Wege zur Optimierung der Supply Chain. München: Verlag Franz Vahlen. These principles can be addressed through the areas of action and measures presented in Table 8.

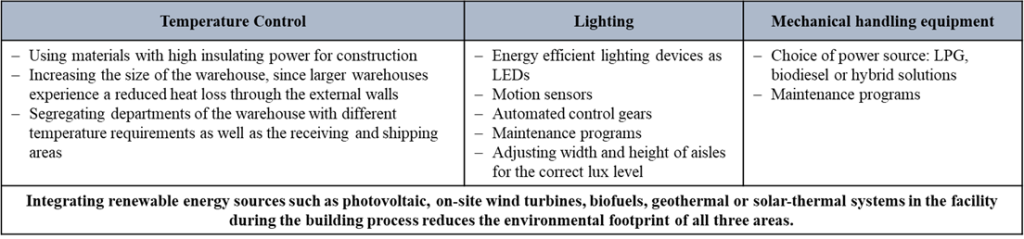

Warehousing interacts with the TBL through the operations itself as well as through the facility that is needed. The sustainability performance of the warehouse facility is already to a large extent predetermined during the development phase.57 Amjed, T. W., & Harrison, N. J. (2013). A Model for sustainable warehousing: from theory to best practices. In A. E. Avery (Ed.), 2013 International DSI and Asia Pacific DSI Conference proceedings (pp. 1892-1919). Decision Sciences Institute. Thus, design principles of Green Building and criteria from the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED – most widely used green building rating system) should be considered. These criteria particularly contribute to achieve a wider use of renewable energy sources and a higher energy efficiency.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain manage-ment (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Warehouse operations mainly influence environmental sustainability through its energy consumption and thus through the emission of greenhouse gases. The main drivers of energy consumption in this respect are temperature control, lighting, and the use of mechanical handling equipment.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Table 9 summarizes best practices for reducing the environmental impact of warehousing operations and the facility itself.

Apart from the environmental sustainability, warehousing also strongly interacts with the social aspects. Warehouse operations must run according to social standards, which means that health and safety of the employees must always be guaranteed. Occupational health and safety (OHS) addresses workplace illness and injuries as well as all forms of paid and unpaid work in all sectors. In warehouses the main hazards are related to vehicle movements, loading and unloading, hazardous substances, noise, fire risk, or manual handling procedures. Accidents and following health issues can be prevented by regular staff training, providing the necessary personal protection equipment (PPE), good organization standards, regular maintenance of MHEs, implementation of rules for warehouse traffic, as well as emergency escape routes.57 Amjed, T. W., & Harrison, N. J. (2013). A Model for sustainable warehousing: from theory to best practices. In A. E. Avery (Ed.), 2013 International DSI and Asia Pacific DSI Conference proceedings (pp. 1892-1919). Decision Sciences Institute. Furthermore, the implementation of equipment for storage and material handling as well as the implementation of IT systems that support picking, routing and sequencing can reduce unnecessary motion of the employees and thus improve safety and health conditions.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

For instance, the courier, delivery and express service provider DHL has launched the ‘Vision Picking’ project, where smart glasses and augmented reality supports employees during the picking process. The smart glasses display information about the location and the number of items, freeing the employees’ hands from paper and thus allowing them to work more efficiently and comfortably.58 DHL. DHL successfully tests augmented reality application in warehouse. Retrieved on 18.08.2021: https://www.dhl.com/global-en/home/about-us/delivered-magazine/articles/2014-2015/dhl-successfully-tests-augmented-reality-application-in-warehouse.html 59 Lehmann, S. (2019). Kommissionieren: DHL rollt neue Datenbrillen-Generation welt-weit aus. Logistik Heute. Retrieved on 18.08.2021: https://logistik-heute.de/news/kommissionieren-dhl-rollt-neue-datenbrillen-generation-weltweit-aus-17556.html

The efficiency and sustainability of transportation as well as warehousing processes can also be improved through logistic-friendly packaging, that helps to achieve higher volume utilization of vehicles and warehouses. Three design features of packaging systems play a major role in this regard: (iso)modularity, stackability and weight. A modular dimensioning of the packaging system in relation to the load carrier helps to fully utilize its surface. Beyond that, height utilization of a load carrier or a loading space is important, which is usually determined by the stackability of the load unit.60 Kye, D., Lee, J., & Lee, K. D. (2013). The perceived impact of packaging logistics on the efficiency of freight transportation (EOT). Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management, 43(8), 707–720. 61 Hellström, D., & Olsson, A. (2017). Managing packaging design for sustainable development: A compass for strategic directions. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell. The stackability of a cargo unit is determined by the strength properties of the packaging and the stability of the load unit.62 Grossmann, G., & Kassmann, M. (2007). Transportsichere Verpackung und Ladungssicherung: Ratgeber für Verpacker, Verlader und Transporteure (2nd edition). Renningen, Germany: Expert-Verlag. Furthermore, different means of transportation are subject to a weight restriction. Thus, light packaging contributes to higher load factors, so that the weight restriction is not reached before the loading space volume is fully utilized.63 Pålsson, H. (2018). Packaging logistics: Strategies to reduce supply chain costs and the environmental impact of packaging (1st edition). London, UK: KoganPage.

For instance, the ice cream manufacturer SIA Glass sells ice cream in elliptic plastic boxes. This way, the pallet can hold a maximum of 896 units of 0.5 litre of ice cream. By switching from an elliptic to a brick packaging system (e.g., BC Glace uses it), SIA Glass could increase the volume utilization of the load carrier substantially. One pallet could then hold a maximum of 1,650 packages of 0.5 litres of ice cream. With almost twice as much ice cream on one pallet, SIA Glass could save a high number of transportation processes and thus a substantial amount of CO2 emissions.61 Hellström, D., & Olsson, A. (2017). Managing packaging design for sustainable development: A compass for strategic directions. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley Blackwell.

3.5 Closed loop supply chain management and reverse logistics

Closed loop supply chain management (CLSCM) refers to all forward as well as reverse logistics flows in the supply chain to ensure a socioeconomically and ecologically sustainable recovery.64 Raj Kumar, N., & Satheesh Kumar, R. M. (2013). Closed Loop Supply Chain Management and Reverse Logistics – A Literature Review. International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology, 6(4), pp. 455-468. ‘Closing the loop’ of an ‘ordinary’ supply chain entails many sustainable advantages such as a decrease in resource and energy consumption and thus a reduction in emissions and waste.64 Raj Kumar, N., & Satheesh Kumar, R. M. (2013). Closed Loop Supply Chain Management and Reverse Logistics – A Literature Review. International Journal of Engineering Research and Technology, 6(4), pp. 455-468.

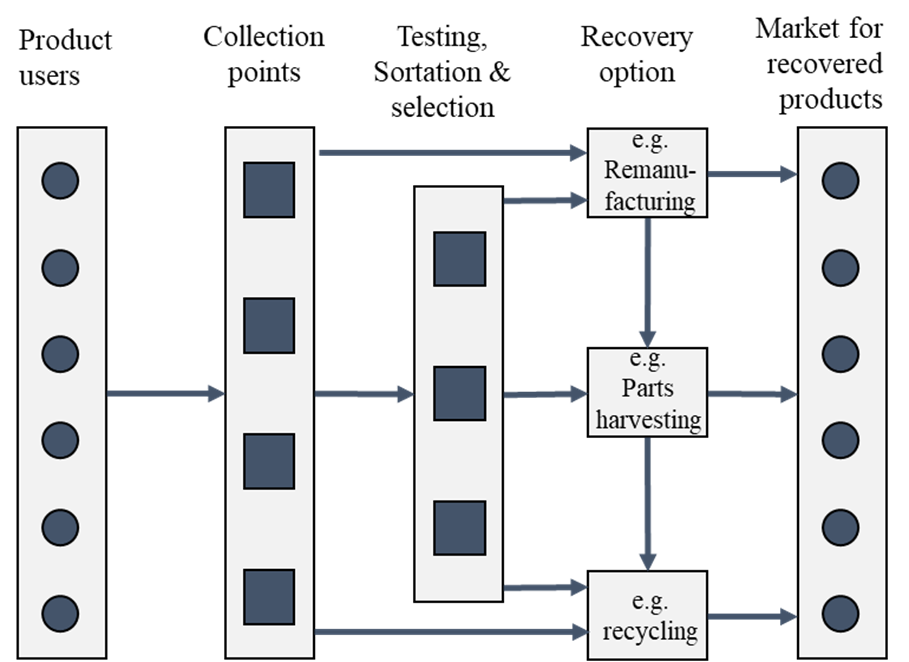

Reverse Logistics is the subprocess, that ensures the product flows to, between and in facilities as shown in Figure 4.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 65 van der Laan, E. A. (2019). Closed Loop Supply Chain Managemenr. In H. Zijm, M. Klumpp, A. Regattieri, & S. Heragu (Eds.), Operations, Logistics and Supply Chain Management (1st ed., pp. 353-375). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing. It includes a range of activities from the collection of the product, testing and inspecting its condition, the sortation and selection according to the type of product and the recovery option, over the recovery itself, and onward the redistribution or disposal.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The following are typical recovery options that allow a company to “close the loop”: Resale (asis) and reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishment, repair, parts harvesting, cannibalization, recycling and disposal with energy recovery.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. The recovery options can be arranged in a hierarchy in terms of potential value creation and the level of eco-efficiency.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Beyond that, the recovered value depends on the trade-off between speed and the costs for the recovery process. A low-cost recovery process is important, because a recovered product already loses approximately 50 % of its value due to the degradation of the product alone. A fast recovery process is crucial since the product loses value due to its time value depreciation.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Source: Based on van der Laan, 2019.65 van der Laan, E. A. (2019). Closed Loop Supply Chain Managemenr. In H. Zijm, M. Klumpp, A. Regattieri, & S. Heragu (Eds.), Operations, Logistics and Supply Chain Man-agement (1st ed., pp. 353-375). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Recovering a high value is also closely linked to the production and manufacturing methods used in the first place. Using techniques such as Design for the Environment, Design for Remanufacturing or Design for Disassembling substantially impact the efficiency and effectiveness of recovery options.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. For instance, the automobile industry has introduced several projects to facilitate the disassembly and reuse of materials, by reducing the number of parts, abandoning chemical bonds and screws, rationalizing the materials and snapfitting components.46 Belvedere, V., & Grando, A. (2017). Sustainable operations and supply chain management (1st edition). Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Apart from that, a modular design reduces the process complexity faced in many recovery processes. It allows component substitution without adjusting other components.66 Krikke, H., Le Blanc, I., & Van de Velde, S. (2004). Product Modularity and the Design of Closed-Loop Supply Chains. California Management Review, 46(2), pp. 22-39.

The computer technology company Dell has changed its product design to enable easy repair and recyclability from the start through the use of a modular product design and postponement as strategies. Furthermore, the multinational company has started its Global Takeback program, which helps customers dispose of old electronics.67 Kumar, S., & Craig, S. Dell, Inc.’s closed loop supply chain for computer assembly plants. Information Knowledge Systems Management, 6, pp. 197-214. 68 Wolk-Lewanowicz, A., Roll, K., Koch, L., & Roberts, S. (2017). The Business Case for a Sustainable Supply Chain. Retrieved on 12.08.2021: https://i.dell.com/sites/doccontent/corporate/corp-comm/en/Documents/circular-case-study.pdf

4 Drivers and barriers

4.1 Internal perspective on SSCM

4.1.1 Internal drivers

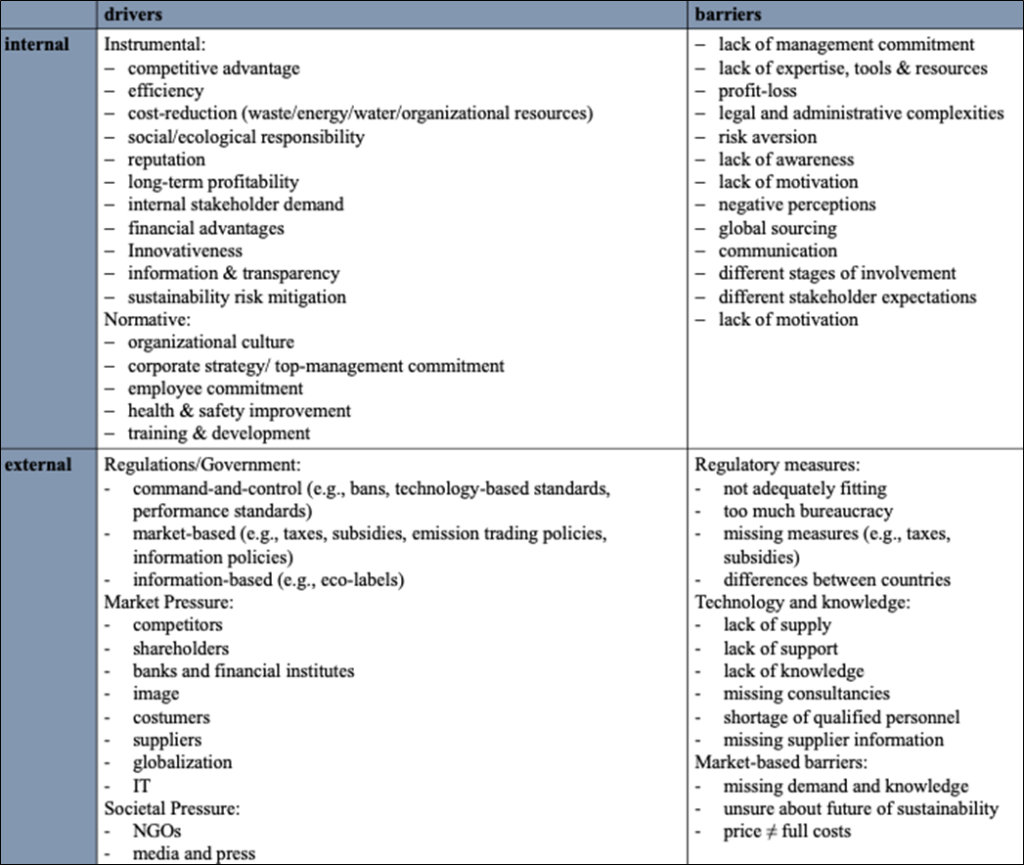

The internal motivation of companies to optimize their supply chains towards sustainability has increased continuously over the past years. Two reasons are found to be particularly relevant for this development. The first is the company’s desire to obtain a competitive advantage through the sustainable alignment of its business strategy and the optimization of its operational efficiency, including the motivation of cost reduction.69 Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Tappin, D. (2015). Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Motivators and Barriers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(7), 643–655. Various studies have shown that investments in sustainability can promote the competitiveness and long-term profit of companies.70 Dauvergne P., & Lister J. (2013). Eco-Business: a Big-Brand Takeover of Sustainability. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 71 Kumar, S., Teichman .S., & Timpernagel, T. (2012). A green supply chain is a requirement for profitability. International Journal of Production Research, 50(5), 1278–1296. The second is the motivation to acquire reputational gain and societal legitimacy, since businesses are facing increased pressure regarding the social and environmental needs of stakeholder groups.69 Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Tappin, D. (2015). Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Motivators and Barriers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(7), 643–655. 70 Dauvergne P., & Lister J. (2013). Eco-Business: a Big-Brand Takeover of Sustainability. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. In addition to the two main drivers, other important internal factors (shown in Table 10), that drive sustainability in the supply chain can be identified.

These can be broadly divided into two subcategories: instrumental and normative factors.

The instrumental dimension assumes that the company is a wealth-creation asset, and that sustainability is seen as a strategic tool to enhance economic goals. The normative dimension, in contrast, is driven by the ethical and moral values of a company’s managers.69 Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Tappin, D. (2015). Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Motivators and Barriers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(7), 643–655. Long-term profitability, for example, can be classified under the instrumental drivers. As mentioned above, investments in sustainability initiatives can make a company competitive and profitable in the long term. An increasing number of consumers want to purchase sustainable products and the company can thus position itself in a growing niche.70 Dauvergne P., & Lister J. (2013). Eco-Business: a Big-Brand Takeover of Sustainability. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. According to the International Panel on Climate Change, companies that have already adapted sustainability measures in their value chain, are better prepared for the consequences of a more severe climate change.72 Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. (2017). Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Retrieved on 20.08.21: https://assets.bbhub.io/company/sites/60/2020/10/FINAL-2017-TCFD-Report-11052018.pdf Furthermore, sustainable companies are rated as less volatile by the financial industry and thus have the opportunity to obtain better loans.73 Van Stekelenburg, A., Georgakopoulos, G., Sotiropoulou, V., Vasileiou, K. Z., & Vlachos, I. (2015). The Relation between Sustainability Performance and Stock Market Returns: An Empirical Analysis of the Dow Jones Sustainability Index Europe. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 7(7), 74–88. Resources are bundled more effectively through an SSCM; thus, operations can be streamlined and costs can be avoided. For instance, costs for energy, waste and water can be reduced.74 Zimon, D., Tyan, J.,& Sroufe, R. (2020). Drivers of sustainable supply chain management: Practices to alignment with UN Sustainable Development Goals. International Journal for Quality Research, 14(1), 219–236. Increased green innovativeness can also be labelled as a driver. Another driver is the demand for a transparent supply chain, which in turn reduces the sustainability related supply chain risks.75 Saeed, M., & Kersten, W. (2019). Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1137–1160.

The normative dimension includes organizational culture and employee commitment. A strong organizational culture with motivated employees can be enhanced by SSCM, as can a convinced top management with a strong corporate strategy. The normative dimension also includes an improved occupational health an safety program and a solid training and development agenda.75 Saeed, M., & Kersten, W. (2019). Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1137–1160.

4.1.2 Internal barriers

Internal barriers include organizational aspects that can hinder the implementation of a sustainable supply chain and are shown in Table 10. Studies suggest that while there are several factors that can prevent companies from adopting SSCM practices, theoretical and empirical research on SSCM barriers is relatively scarce compared to motivators of SSCM implementation.69 Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Tappin, D. (2015). Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Motivators and Barriers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(7), 643–655. Top- and middle management support and commitment are important factors influencing the implementation of a SSCM strategy in companies.74 Zimon, D., Tyan, J.,& Sroufe, R. (2020). Drivers of sustainable supply chain management: Practices to alignment with UN Sustainable Development Goals. International Journal for Quality Research, 14(1), 219–236. 75 Saeed, M., & Kersten, W. (2019). Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1137–1160. However, a lack of interest from top management can significantly hinder the ability of companies to engage in sustainability initiatives.69 Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Tappin, D. (2015). Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Motivators and Barriers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(7), 643–655. .Implementing a SSCM requires the development of infrastructures, systems and processes in the supply chain, which can increase operational costs. Thus, due to financial constraints, companies often struggle to implement SSCM.76 Tay, M. Y., Rahman, A. A., Aziz, Y. A., & Sidek, S. (2015). A Review on Drivers and Barriers towards Sustainable Supply Chain Practices. International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, 5(10), 892–897. Legal and administrative complexity, risk-averse behavior, lack of awareness and motivation or negative perceptions of green procurement are some of the main factors that hinder a company’s sustainable procurement efforts.69 Sajjad, A., Eweje, G., & Tappin, D. (2015). Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Motivators and Barriers. Business Strategy and the Environment, 24(7), 643–655. A complex supply chain that is spread across the globe can lead to problems due to its regional scope, as well as communication problems. In addition, different stages of development as well as varying motivations of supply chain partners can cause difficulties. Various internal stakeholders may have different expectations and demands that need to be addressed in diverse ways. For example, employees are more interested in work-related health and safety conditions, while supply chain partners are more interested in efficient logistics.75 Saeed, M., & Kersten, W. (2019). Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1137–1160. Several specific factors within the supply chain can pose barriers. These include the position in the chain, the industrial sector, the size, the geographical location, the degree of internationalization and the current level of sustainability involvement.75 Saeed, M., & Kersten, W. (2019). Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1137–1160.

However, organizations can find a way to overcome internal barriers. Even if there is no one-fits-all solution, a best practice example by Patagonia, a supplier for outdoor clothing, illustrates how to overcome limits like transparency, communication, and involvement across the supply chain. Especially in the fashion industry, sustainability in the supply chain is a topic that is demanded by an increasing number of stakeholders. At the same time, the internal barriers are particularly high due to cost pressure, long supply chains and the resulting communication and transparency problems.77 Oelze, N. (2017). Sustainable Supply Chain Management Implementation–Enablers and Barriers in the Textile Industry. Sustainability, 9(8), 1435–1450. Nevertheless, Patagonia has managed to establish itself to overcome these challenges. Among many other sustainability-related measures, in 2001 the company became a founding member of the Fair Labor Association, a nonprofit organization dedicated to improving working conditions worldwide. In 2011, the company moved further to the beginning of the value chain, joining Fair Trade USA’s apparel program in 2014 to monitor working conditions in the factories that produce its fabrics.78 Patagonia. (2020). Partnering with the People Who Make Our Clothing, with Fair Trade Practices. Retrieved on 20.08.21: https://www.patagonia.com/stories/partnering-with-the-people-who-make-our-clothing/story-33158.html In 2017, a study conducted with 10 companies in the fashion industry showed that textile companies that collaborate with stakeholders or even competitors save resources and can keep up with sustainability improvements on the supplier side by conducting audits together. In addition, sharing knowledge about sustainability issues is a widespread incentive to collaborate with other companies.77 Oelze, N. (2017). Sustainable Supply Chain Management Implementation–Enablers and Barriers in the Textile Industry. Sustainability, 9(8), 1435–1450.

4.2 External perspective on SSCM

4.2.1 External drivers

The implementation of sustainability within the supply chain can also be triggered by drivers outside the company. As the influential groups vary, Saeed and Kersten (2019) differentiated them into three categories, also displayed in Table 10: regulations/government, market pressure and societal pressure.75 Saeed, M., & Kersten, W. (2019). Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1137–1160.

Regulations/Government

Regulatory measures set by the government are among the most common and efficient drivers of sustainability within the supply chain. They can differ in their degree of hardness, from non-regulatory approaches, over market-based regulations up to command-and-control measures.79 Sarkis, J. (2019): Handbook on the Sustainable Supply Chain. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

The use of command-and-control measures is a mandatory tool that all involved market players must comply with.By not doing so, companies risk paying additional fines or having trade barriers imposed against them. One particular and rather vigorous way of regulating supply chains is through bans.79 Sarkis, J. (2019): Handbook on the Sustainable Supply Chain. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. A common example is the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS), currently restricting ten hazardous substances within electronic applications in the EU.80 European Commission (2011). Restriction of Hazardous Substances in Electrical and Electronic Equipment (RoHS). Retrieved on 01.08.2021:

https://ec.europa.eu/environment/topics/waste-and-recycling/rohs-directive_de The effects of bans are more extensive, as imported pieces from foreign suppliers also have to comply; consequently, operations outside the EU are also influenced.81 Koh, S., Gunasekaran, A., & Tseng, C. S. (2012): Cross-tier ripple and indirect effects of directives WEEE and RoHS on greening a supply chain. International Journal of Production Economics, 140(1), 305–317. Other forms of complying regulatory measures are technology-based or performance standards. Technology-based approaches determine a precise measure which has to be applied by companies, such as implementing new machinery.82 Goulder, L. H., & Parry, I. W. (2008). Instrument choice in environmental policy. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, 2(2), 152–174. In contrast, performance standards do not define, for example, the way that pollution reduction is achieved but sets a level of emissions permitted, giving companies more flexibility. Like bans, these regulatory measures have an impact on the supply chain, as a necessary reduction of emissions or an increase of efficiency will partially be forwarded to suppliers.75 Saeed, M., & Kersten, W. (2019). Drivers of Sustainable Supply Chain Management: Identification and Classification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1137–1160.

In June 2021, the German Bundestag has launched the new Supply Chain Act (Lieferkettengesetz), a regulatory measure focusing precisely on the supply chain. Its intention is to protect and improve human rights within the global supply chain. Therefore, focal firms are determined to bear more responsibility for their suppliers. The closer the supplier is and the more impact the focal firm has, the more responsibility it carries. In case of violations, fines are incurred.83 Bundesministerium für wirtschaftliche Zusammenarbeit und Entwicklung (2021). Das Lieferkettengesetz ist da. Retrieved on 15.08.2021:

https://www.bmz.de/de/entwicklungspolitik/lieferkettengesetz Even though the Act has been received positively, organizations have also criticized it for not going wide enough. For instance, Oxfam, WWF, and Germanwatch have denounced that workers at plantations are not able to sue the German focal firm at German court for violating human rights. Furthermore, they only have to look after their direct suppliers, which are their connections to areas where human rights are violated. However, they still see it as a partial victory with the hope of more to come.84 Oxfam Deutschland (2021). Lieferkettengesetz: Für Menschenrechte in der Wirtschaft. Retrieved on 15.08.202: https://www.oxfam.de/unsere-arbeit/themen/lieferkettengesetz 85 WWF (2021). Das deutsche Lieferkettengesetz. Retrieved on 15.08.2021: https://www.wwf.de/themen-projekte/politische-arbeit/wir-brauchen-ein-starkes-lieferkettengesetz 86 Germanwatch (2021). Noch nicht am Ziel, aber endlich am Ziel: Lieferkettengesetz verabschiedet! Retrieved on 15.08.2021: https://germanwatch.org/de/20328

Vice versa market-based measures focus on the self-regulation of the market by introducing incentives such as taxes, subsidies, or emission trading policies. These measures are still compelling for all participants but offer more flexibility and adapt to the market. The resulting higher or lower costs cause companies to reduce emissions by adapting their operations due to the principle of economic efficiency. These adaptions not only affect the primary company but also all its suppliers, even leading to a possible change of suppliers. Another non-monetary but still mandatory market-based measure is the utilization information policies like the European Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), which obliges larger companies to publish information about their sustainable activities. As companies must publish their corporate data, they have become more concerned about acting sustainably for various reasons, such as keeping up appearances with stakeholders.79 Sarkis, J. (2019): Handbook on the Sustainable Supply Chain. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. 87 US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2010). Regulatory and non-regulatory aproaches to pollution control. Guidelines for Preparing Economic Analyses. 88 European Commission (2017). Guidelines on non-financial reporting | Together Against Trafficking in Human Beings. Retrieved on 10.08.2021: https://ec.europa.eu/anti-trafficking/eu-policy/guidelines-non-financial-reporting_en However, more transparency does not only benefit consumers at the end of the supply chain but also companies within the supply chain, as information about their suppliers are available more easily.89 European Commission; Directorate General for Justice and Consumers. (ed.); British Institute of International and Comparative Law. (ed.); Civic Consulting. (ed.); LSE. (ed.) (2020): Study on due diligence requirements through the supply chain: final report. Publica-tions Office.

On the voluntary level information-based measures, such as eco-labels are a very common driver of sustainability. The relevance of these labels depends on the interest of stakeholders in sustainability, as they are mostly used to convince customers about companies’ sustainable actions.87 US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) (2010). Regulatory and non-regulatory aproaches to pollution control. Guidelines for Preparing Economic Analyses. An example is the Fairtrade label, which promotes stable prices, long term trade relations and e.g., good working conditions within the supply chain, especially for smallholder farmers.90 Fairtrade Deutschland (2021). Fairtrade-Siegel – Auf einen Blick. Retrieved on 02.08.2021: https://www.fairtrade-deutschland.de/was-ist-fairtrade/fairtrade-siegel Additionally, the Rainforest Alliance certification discloses products which comply with standards for environmental and social sustainability in the supply chain. In 2007 Unilever decided to adapt the Rainforest Alliance standards for its tea supply chain, with the intention of making their sustainable activities visible for consumers and to increase credibility.91 IMD (2011a) Case Study: Unilever Tea (A): Revitalizing Lipton’s supply chain. Lausanne, Switzerland. With the implementation of the certificate, tea famers of Unilever have been evaluated and audited and were provided with technical assistance, motivation, and skills.92 IMD (2011b) Case Study: Unilever Tea (B): Going beyond the low-hanging fruits. Lausanne, Switzerland.

Last, also public procurement is considered as a driver of SSCM, as global expenditures on public procurement account for between 13 % and 20 % of the GDP, being nearly $9.5 trillion.93 World Bank (2021). Global Public Procurement Database: Share, Compare, Improve! Retrieved on 10.08.2021: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/03/23/global-public-procurement-database-share-compare-improve

Market Pressure

Market pressure is another important issue, as the relevance of sustainability in the market is increasing.94 European Commission (2020). New Eurobarometer Survey: Protecting the environment and climate is important for over 90% of European citizens. Retrieved on 08.08.2021: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_331 Concerning the specific drivers on the market, competition is pressuring the company either to achieve a competitive advantage or at least keeping up with the competitors. On the monetary level, companies are dependent on their shareholders as well as banks and financial institutes, which are also increasingly demanding sustainable actions.79 Sarkis, J. (2019): Handbook on the Sustainable Supply Chain. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. In 2019 the US retailer Walmart partnered with the international financial institute HSBC with the intention to promote sustainable supply chains, by introducing a sustainable supply-chain financing program. The program addresses Walmart’s suppliers, granting them better credit rates based on their environmental and social performance.95 HSBC (2019). HSBC and Walmart partner to drive sustainability of businesses. Retrieved on 10.08.2021: https://www.business.hsbc.com/sustainability/hsbc-and-walmart-partner-to-drive-sustainability-of-businesses

Other important drivers of sustainability overall are the costumers along with the company’s image.96 Tate, W. L., Ellram, L. M., & Kirchoff, J. F. (2010). Corporate social responsibility reports: A thematic analysis related to supply chain management. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 46, 19–44. However, the effect on the supply chain is conceived not only indirectly from the demand for sustainability in the focal firm, but also directly from the demands of customers for sustainability within the supply chain. 97 Berg, A., Hedrich, S., Ibanez, P., Kappelmark, S., Magnus, K.-H., & Seeger, M. (2019). Fashion’s new must-have: Sustainable sourcing at scale. McKinsey Apparel CPO Survey 2019.

Although suppliers are often pressured to react to the demands of the focal firm, they can also act as drivers that provide the main company with a variety of sustainable products it can purchase.98 Alblas, A. A., Peters, K., & Wortmann, J. C. (2014). Fuzzy sustainability incentives in new product development. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 34, 513–545. This coincides with the overall term of globalization, since different markets worldwide are available, making the purchase of specific products easier and accordingly increasing the flexibility of companies.99 Xu, L., Mathiyazhagan, K., Govindan, K., Noorul Haq, A., Ramachandran, N. V., & Ashokkumar, A. (2013). Multiple comparative studies of Green Supply Chain Management: Pressures analysis. Resources Conservation and Recycling, 78, 26–35.