Authors: Hannah Dahmen, Marco Dorow, Rebecca Katharina Hillebrandt, Mareike Ropers

Last updated: December 7, 2022

1 Definition and relevance

1.1 Communication and corporate communication

Communication can be defined as the transmission of meaning between living beings. 1K. Scherer and H. Wallbott, Nonverbale Kommunikation. Forschungsberichte zum Interaktionsverhalten, Weinheim, 1979. More specifically, human communication can be defined as the human and technologically based activity of the reciprocal use and interpretation of signs for the purpose of successful understanding, coordinating action and shaping reality. 2D. Krallmann and A. Ziemann, Grundkurs Kommunikationswissenschaft, München: Fink, 2001. It always includes a person who says something (communicator), a person who receives what is said (recipient), and the statement itself. 3G. Kittelmann, Zur Bedeutung des Faktors Nachhaltigkeit für die Unternehmenskommunikation am Beispiel des Kuratoriums UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe Museumsinsel Berlin, Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 2015. Further, communication always serves a purpose: the affection of other(s)’ feelings, thoughts or even behaviors. 4R. Genç, “The Importance of Communication in Sustainability & Sustainable Strategies,” Procedia manufacturing, pp. 511-516, 2017.

Based on this understanding of communication, corporate communication (CC) can generally be defined as the entirety of all communicative processes (both formal and informal) between a company and its internal and external environments, which are employed to perceive, address, and influence the respective. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020. Further definitions highlight certain aspects and functions of CC, such as the contribution to the definition and fulfillment of tasks as well as the coordination of action and clarification of interests between stakeholders, 3G. Kittelmann, Zur Bedeutung des Faktors Nachhaltigkeit für die Unternehmenskommunikation am Beispiel des Kuratoriums UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe Museumsinsel Berlin, Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 2015., 6A. Zerfaß, Unternehmensführung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Unternehmenskommunikation und Public Relations, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1996., 7A. Zerfaß, “Unternehmenskommunikation und Kommunikationsmanagement: Grundlagen, Wertschöpfung, Integration,” in Handbuch Unternehmenskommunikation, Wiesbaden, Gabler, 2007, pp. 21-70. the presentation of a company’s performance, 8M. Bruhn, Integrierte Unternehmenskommunikation: Ansatzpunkte für eine strategische und operative Umsetzung integrierter Kommunikationsarbeit, Stuttgart, 1995. the conveyance of a company’s identity, 9H. Raffee and K.-P. Wiedmann, Strategisches Marketing, 1989. and the relationship-building capacity. 10R. Borchelt and K. Nielsen, “Relations in Science. Managing the trust portfolio,” in Routledge Handbook of Public Communication of Science and Technology, London, New York, Routledge, TAylor & Francis Group, 2014.

Most definitions mention both the internal and external environment, indicating a distinction of various spheres, so-called contact fields, with various stakeholders, in the CC context referred to as reference groups, which are actors with which the company maintains a relationship and at whom the CC is addressed. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020., 11H. Avenarius, Public Relations. Die Grundform der gesellschaftlichen Kommunikation, Darmstadt, 2000. CC has a multitude of stakeholders, each of whom requires appropriate CC, as goals, intentions, as well as requirements of content and style differ. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020., 12M. Hillmann, Das 1×1 der Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Wegweiser Für Die Praxis, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2017.

Zerfaß distinguishes between internal CC and two forms of external CC, which are market communication and public relations (PR). 6A. Zerfaß, Unternehmensführung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Unternehmenskommunikation und Public Relations, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1996. Internal CC comprises of all communicative processes taking place within a company between its members, i.e., within the internal organizational environment. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020. External CC is defined as all communicative activities of a company with partners outside the spatial or organizational boundaries of the company. 3G. Kittelmann, Zur Bedeutung des Faktors Nachhaltigkeit für die Unternehmenskommunikation am Beispiel des Kuratoriums UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe Museumsinsel Berlin, Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 2015. Here, market communication occurs with partners from a market environment. Such market environments are the sales market for products and services, i.e., with (potential) customers, the labor market, i.e., with (potential) employees, the capital market, i.e., with (potential) investors, and the procurement market, i.e., with (potential) suppliers. 6A. Zerfaß, Unternehmensführung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. Grundlagen einer Theorie der Unternehmenskommunikation und Public Relations, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1996. PR takes place within a firm’s societal and political environment. The societal sphere can be further differentiated into the socio-political sphere of opinion leaders and journalists and the socio-cultural sphere of residents, critics, and scientists. 6A. Zerfaß, Unternehmensführung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. Grundlegung einer Theorie der Unternehmenkommunikation und Public Relations., vol. 2. ergänzte Auflage, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, 2004.

1.2 Corporate sustainability communication

Corporate Sustainability Communication (CSC) is defined as an evolving concept that refers to CC about sustainability issues (i.e., the topic of sustainability or its dimensions ecology, social responsibility, and economy, as well as their partially and potentially conflicting goals). 13C. Axmann, Nachhaltigkeit und Unternehmenskommunikation. Theoretische Aspekte und empirische Ergenisse zur Umsetzung des Nachhaltikeitsleitbildes in der Unternehmenskommunikation am Beispiel von Volkswagen, Braunschweig: Technische Universität Carolo Wilhelmina zu Braunschweig, 2008., 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. Within the company, CSC is not to be regarded as an additional branch to CC, but as the integration of sustainability issues into existing CC programs. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007.

1.3 Practical relevance of corporate sustainability communication

CSC is of relevance for companies for a multitude of reasons. Most of them resulting from the fact, that CSC carries sizeable benefits for the economic success of firms, i.e., being long-term profit-maximizing (e.g. via reducing costs and risks, gaining competitive advantage, developing reputation and legitimacy). 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014., 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007., 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010. Generally, CC is vital for a company’s business success, as it serves the functions of informing, convincing, motivating, and providing mutual understanding. 4R. Genç, “The Importance of Communication in Sustainability & Sustainable Strategies,” Procedia manufacturing, pp. 511-516, 2017. Moreover, CC in general and CSC specifically serve the function of identifying, internalizing, and processing relevant sustainability issues. 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010., 17S. Schaltegger and R. Burritt, “Corporate Sustainability,” in The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006. A Survey of Current Issues, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 2005, pp. 185-222. These functions are especially important in the case of CSC, as sustainability issues are characterized by high complexity, uncertainty, and recognizable potential for conflict between the three dimensions, as well as a company’s various stakeholders. Hence, it makes sense to focus on the communication of sustainability issues specifically. 18C. Mast and K. Fiedler, “Nachhaltige Unternehmenskommunikation,” in Handbuch Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation.Grundlagen und Praxis, München, Oekom Verlag, 2005, pp. 565-575., 19J. Newig, J.-P. Voß and J. Monstadt, Governance for Sustainable Development: Coping with Ambivalence, Uncertainty and Distributed Power, London: Routledge, 2008. As sustainability has gained growing attention and has become increasingly important in society in the last years, both formally (through legislation and regulation) and informally, communication about corporate sustainability (CS) is becoming increasingly relevant for companies to maintain legitimacy. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020., 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010., 20J. e. a. Newig, “Communication Regarding Sustainability: Conceptual Perspectives and Exploration of Societal Subsystems,” Sustainability, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 2976-2990, 2013. The increased attention and importance of sustainability in society further encompasses growing relevance within the market sphere: for traditional product marketing, to increase sales, on the labor market, to be perceived as an attractive employer, and on the financial market, to receive high ratings and facilitate financing. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014., 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010. Also, internal CSC is of high relevance, as it is of particular importance for the anchoring of a firm’s sustainability commitment at its base. The relevance of the involvement of employees into sustainability processes for their effectivity has been numerously shown in various studies. 21M. Eisenegger and M. Schranz, “CSR – Moralisierung des Reputationsmanagements,” in Handbuch CSR, Wiesbaden, 2011, pp. 71-92.

Signitzer and Prexl (2008) distinguish between three cases to group reasons and motives to practice CSC (importantly, the cases are not clearly distinct, but serve as a framework for categorization) 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007.: First, CSC serves a business case from an organizational perspective (contribution to sustainability goals or company as such). With respect to in- and external stakeholders, CSC can improve an organization’s image and reputation and thereby help keeping a license to operate. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007., 22T. Münzing and P. Zollinger, “Zielgruppen und Inhalte [Stakeholder groups and contents],” in Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation für Unternehmen und Institutionen [Sustainability communications for companies and institutions], Neuwied, Luchterhand, 2001, pp. 22-46., 23C. Biedermann, “Corporate Citizenship in der Unternehmenskommunikation,” in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland, Wiesbaden, 2010, pp. 353-370. Importantly, external stakeholders are indirectly affected via internal stakeholders: through positive comments in the professional and private lives, employees, who identify with their employer and products, can serve as multipliers of positive reputation. 12M. Hillmann, Das 1×1 der Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Wegweiser Für Die Praxis, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2017. Internally, CSC has the potential to initiate sustainability understanding, engagement, learning, and (bottom-up) change processes (implementation and execution) and can thereby be a catalyst for innovation, cost reduction and competitive advantage. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014., 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007., 24J. e. a. Sarkis, “Organizational restructuring implications for corporate sustainability,” in Communicating sustainability, Frankfurt, Peter Lang, 2000, pp. 173-196. Moreover, CSC is crucial for organizational sustainability changes, as their implementation involves multiple corporate systems, such as top, legal, research and development, quality, human resources, and communication management, which need to be integrated and harmonized. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007. By positioning a company as a sustainable organization with sustainable products, CSC can increase employee identification, loyalty, retention, engagement, and motivation. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020., 12M. Hillmann, Das 1×1 der Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Wegweiser Für Die Praxis, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2017., 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014., 17S. Schaltegger and R. Burritt, “Corporate Sustainability,” in The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 2005/2006. A Survey of Current Issues, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar, 2005, pp. 185-222., 23C. Biedermann, “Corporate Citizenship in der Unternehmenskommunikation,” in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland, Wiesbaden, 2010, pp. 353-370. Further, this can increase a company’s attractivity as an employer, enabling a company to recruit qualified and motivated employees. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014., 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010. Moreover, trust and credibility among customers can be enhanced. Targeting the political sphere through lobbying, CSC can initiate new (environmental and social) regulations. 6A. Zerfaß, Unternehmensführung und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. Grundlegung einer Theorie der Unternehmenkommunikation und Public Relations., vol. 2. ergänzte Auflage, Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, 2004. Within the financial sphere and the capital market, CSC has the potential to improve the rating of a firm with banks, investors, insurance companies, or in financial rankings. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007., 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010.

Second, a marketing case for CSC exists (contribution to marketing goals). CSC serves the function of increasing sales (of sustainable products) by gaining new and retaining existing customers through building relations with customers, fostering market and product placement and differentiation. 23C. Biedermann, “Corporate Citizenship in der Unternehmenskommunikation,” in Corporate Citizenship in Deutschland, Wiesbaden, 2010, pp. 353-370. CSC with suppliers on the procurement market can sensitize these for sustainability issues and thereby enable them to understand the issue further and comply with the communicated sustainability strategy and requirements. 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010., 25P. Hauth and M. Raupach, “Nachhaltigkeitsberichte schaffen Vertrauen,” Harvard Business Manager, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 24-33, 2001. Subtly, by increasing sensitivity towards and knowledge of sustainability amongst employees, CSC can foster the creation of more sustainable products and production processes. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

Moreover, CSC has a societal case (contribution to sustainable development of a society and communication about it). CSC can foster public communication about and increase the public’s awareness and knowledge of sustainability. 26R. Weiss, “Corporate social responsibility und corporate citizenship,” in Handbuch Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation. Grundlagen und Praxis, München, Oekom Verlag, 2005, pp. 588-598. Furthermore, on a broad societal level, CSC has the potential to result into enlightened purchasing decisions and more sustainable behavior in general. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007., 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010.

2 Background

CSC developed on the basis of Corporate Social Reports, an instrument for demonstrating socially responsible behavior as an advertising tool and environmental communication programs of the 1970s and 1980s, when environmental scandals such as the chemical disasters in Seveso, Italy in 1976 and in Bhopal, India in 1984 became the focus of public attention. 27K. Fichter, Umweltkommunikation und Wettbewerbsfähigkeit im Licht empirisher Ergebnisse zur Umweltberichterstattung von Unternehmen, Marburg: Metropolis Verlage, 1998. The communication programs emerged under increasing media pressure as crisis communication and one-sided reporting of ecological success stories. 28U. Kuckartz, U. Schack and H. Bruhn, Umweltkommunikation gestalten, Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 2002. Since the 1990s, the requirements for companies to report on sustainability issues have increased. The 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill off the coast of Alaska was a turning point for stakeholders and investors: awareness of the need for greater transparency about corporate activities and their impact on the environment, society, and the economy grew. Since the 2000s, pressure on companies to report transparently and holistically, and thus to be accountable, has come mostly from capital market-driven initiatives and new legislation. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020. The German Accounting Law Modernization Act (Bilanzmodernisierungsgesetz (BilMoG)) of 2004 established an obligation for large corporations and groups to report on corporate responsibility aspects in the management report. Non-financial performance indicators such as “information on environmental and employee matters insofar as they are of significance for an understanding of the course of business or the situation” (§§ 289, 315 HGB) were to be reported. However, this type of reporting was regarded as a marketing tool and not as a management tool for the business model. The financial crisis from 2007 onward showed that financial information is not sufficient for assessing the social situation and forecasting future development. It became apparent that a view of a company’s value chain and an understanding of stakeholder expectations and interactions between the corporate environment and the company are crucial as well. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020. However, since the topic of sustainability has been communicated, companies have encountered difficulties in implementing their CSC due to complexity, contradictory nature or difficult perceptibility of the topic. 30C. Pfeiffer, Integrierte Kommunikation von Sustainability-Netzwerken: Grundlagen und Gestaltung der Kommunikation nachhaltigkeitsorientierter intersektoraler Kooperationen, Lang, 2004. Since marketing-based communication models have proven insufficient for communicating environmental and social engagement, companies have started to use socially oriented approaches such as corporate social responsibility (CSR) and corporate citizenship for CSC in practice. 31M. Mesterharm, Integrierte Umweltkommunikation von Unternehmen, Metropolis Verlag, 2001., 18C. Mast and K. Fiedler, “Nachhaltige Unternehmenskommunikation,” in Handbuch Nachhaltigkeitskommunikation.Grundlagen und Praxis, München, Oekom Verlag, 2005, pp. 565-575. However, they are only of limited use for comprehensive CSC because of the missing measurable objectives and the fact that only social sustainability aspects are taken into account. 32C. Mast und K. Fielder, Nachhaltige Unternehmenskommunikation, München: Oekom, 2005. The increased inclusion of CSR initiatives in communication is driven by stakeholders, who ask companies to present their measures. 33F. Skoglund, How to communicate environmental efforts for value creation, Uppsala: Swedish University of Agricultural Science, 2015. Already the search for the target group-appropriate messages of the suitable communication strategy can cause the consolidation of the position of the enterprise with critical stakeholders. 34M. Morsing and M. Schultz, Corporate social responsibility communication: stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 2006. It has shown, that with the communication of a CSR strategy, external criticism increases, which is why some companies avoid communicating their CSR measures. 35J. Graafland, Does Corporate Social Responsibility Put Reputationat Risk by Inviting Activist Targeting? An EmpiricalTest among European SMEs, Tilburg, 2017. According to the different ways companies design and use their CSR communication, three types of CSR communication strategies with stakeholders can be distinguished: the information, the response, and the participation strategy. Following the information strategy, stakeholders are informed about the company via one-way channels of websites and sustainability reports. Communication emanates from the company itself and external opinions are not considered. As a result, stakeholders react to the communicated CSR measures in the form of acceptance, support, rejection or boycotting. The underlying incentive of the companies can be the fear of negative press or the will to take responsibility. According to the response strategy, the company communicates in the two asymmetric ways from first analyzing the external environment via dialogue (debates, surveys or communication with stakeholders) to influencing stakeholders through informative communication. The company’s intention is to identify potential improvements to its CSR initiatives. However, the company intends to influence stakeholders’ opinions instead of making its own adjustments based on stakeholder opinions. The participation strategy is based on symmetrical communication between the company and its stakeholders, as the stakeholders are called upon to participate and actively take part. 34M. Morsing and M. Schultz, Corporate social responsibility communication: stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 2006. Resulting positive statements about the CSR activities of third parties increase their credibility and makes it easier to identify potential risks. CSC offers companies new opportunities to build trust and raise their profile, but it also entails a commitment to more symmetrical and open forms of communication with their stakeholders. 36A. Severin, “Nachhaltigkeit als Herausforderung für das Kommunikationsmanagement in Unternehmen,” in Handbuch Nachhaltigkeitkommunikation, München, Oekom-Verlag, 2007, pp. 64-75.

Overall, the pressure on companies increased from investors, stakeholders, the global community, and financial market players and their demands for the implementation of soft laws, such as the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) or support for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). 37OECD, “Soft law,” [Online]. Available: https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/irc10.htm. [Accessed 7 September 2022]. The companies became aware that with increased transparency they could minimize the risk of reputational damage and increase earnings through differentiated positioning on the market. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020. Since 2000, the UNGC has called on companies to voluntarily align their strategies and operations with ten universal principles on human rights, labor standards, environmental protection and anti-corruption, and to take action to advance related social goals. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020. Due to the lack of voluntary implementation, the CSR Directive (Non-Financial Reporting Directive – NFRD) became a legal obligation at European level in 2014. This was transposed into national law in 2017 with the CSR Directive Implementation Act (CSR-RUG) and obliges capital market-oriented companies with an annual average of more than 500 employees to submit a non-financial statement. The reporting of the capital market-oriented companies in Germany affected by the CSR reporting obligation varies greatly depending on the environmental topic. 38C. Lautermann, E. Hoffmann and C. Young, “Empfehlungen für die Gestaltung von Standards zur Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung im Rahmen der Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive,” Berlin, 2021. The difficulty for companies lies in the diversity of existing reporting frameworks 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020. and the fact that so far only a few companies report consistently on environmental issues, providing meaningful information on targets, measures and results. 38C. Lautermann, E. Hoffmann and C. Young, “Empfehlungen für die Gestaltung von Standards zur Nachhaltigkeitsberichterstattung im Rahmen der Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive,” Berlin, 2021.

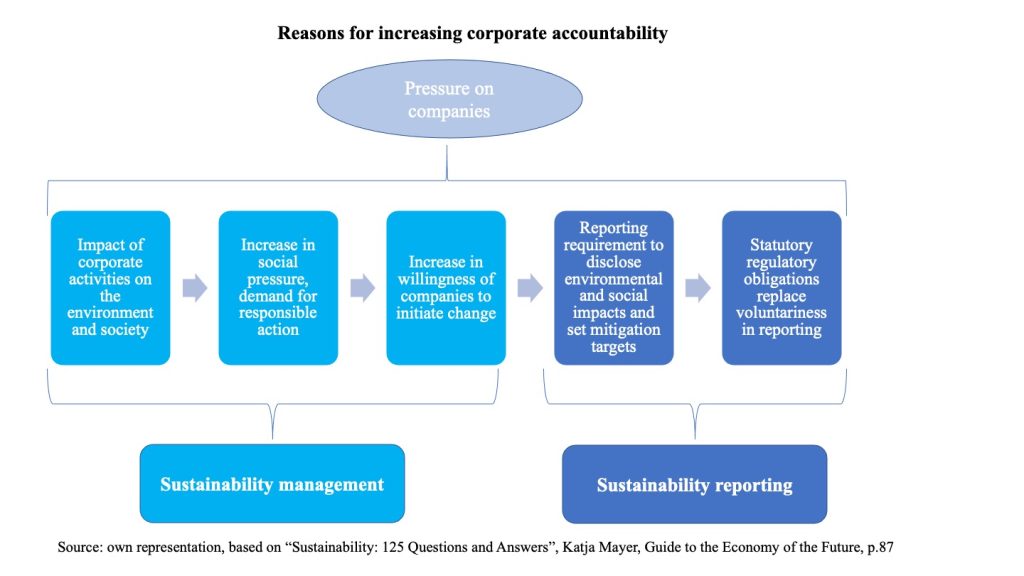

Sustainability has become one of the most important success factors which influences the environment in which companies operate and make companies think differently (see Figure 1). 39KMPG, Expect the unexpected: building business value in a changing world, executive, 2012. Companies are increasingly being called upon to face up to their responsibility towards the environment and society and to provide transparent CSC. 40F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unernehmenskommunikation, 2016. Politically driven legislation supports the shift in focus from PR reports with greenwashing to strategic anchoring of sustainability in the company and reporting in CSR reports with guidelines and regulations. CSC is now considered an active management tool and can be used as a management element to meet stakeholder demands. 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010.

3 Practical implementation

3.1 Communication style

To identify how communication can be used to influence individual-level behavioural change or communicate cooperate sustainability affairs, concrete message strategies and interpersonal communication are an integral part of a cooperate communication. 41M. Allen, Strategic Communication for Sustainable Organizations: Theory and Practice, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer, 2016. Communication about change is most successful when messages are designed by people talking about people to respective stakeholder groups using lively and descriptive phrases and concrete examples. A very helpful channel to do so is to address their emotions and feelings as they decide how they value their environment and how they react to changes. Since emotions can have a two-way effect, it is important to know which communication requirements should be met. Generally, it is important to reduce uncertainties quickly and avoid disagreements at all costs as they can build up emotional barriers that are not easy to overcome. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020. Trust and credibility are important factors when it comes to communication, too. Any CSR activity can be understood as an attempt to gain and to maintain public trust and credibility in order to meet societal expectations. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. Storytelling is another way of communicating corporate sustainability efforts by presenting projects, interviews or telling a narrative story as they are remembered better than a pure depiction of facts. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114.

3.1.1 Language choice

An active, personal language in the narrative style appears colourful, close to people and engaged. It follows a common thread, is easy to understand and can also be retold. An example: “We are working on a way to avoid multiple data entry. This is urgently needed because our customers expect faster processing of orders. Once we achieve this, it will be easier and simpler for both production and sales staff.” 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020.

3.1.2 Simplicity

To keep messages simple is crucial. The people responsible for change projects have accumulated a great extent of detailed knowledge about a topic. However, when talking to stakeholders limiting themselves to the essentials and make rigid selections is important. The words they use should be of common knowledge as much as possible. It is also of importance to form short, simple sentences. Technical terms, foreign words or anglicisms can be replaced by common vocabulary. If a technical term is nevertheless unavoidable, it must be explained in any case. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020.

3.1.3 Wording and length

Impersonal phrases, e.g., passive sentences or phrases with “it” or “one” seem very abstract. They conceal who is active or responsible or who sets the goal. The acting party remains in the background. Such impersonal language is not only difficult to understand – in the case of change, it generates a feeling of distance. Instead of “It is expected that this will be implemented.”, it is better to frame it: “We are asking you to implement this.” Nominalization and nested sentences are often the product of texts that have been framed in cooperation with several departments. However, they create enormously high hurdles for the recipient to understand. In addition, they offer little reading incentive. The consequence is that complicated texts are not used. Therefore, communicators should check every word and every sentence and decide whether it is understandable and evaluate whether the wording suits the target group to be addressed. The essence is to keep messages short which also applies to corporate communications. Interlocutors or customers do not have unlimited time. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020.

3.1.4 Trust and credibility

Processes of gaining and losing trust depend heavily on information conveyed through media, professional public relation, and private publications. Trust is developed and gained in protracted, slow, steady processes. Under certain circumstances, for example during crisis, it can erode rather very fast. For instance, if discrepancies accumulate in a crisis and the more discrepancies are perceived, the more trust is withdrawn. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. According to Bentele (1994), there exist several kinds of discrepancies, for example, untruth, lies, or euphemistic information refer to discrepancies between information and actual facts. Another common discrepancy is a conflict between verbal statements and actual actions like delaying tactics or gamesmanship. 43G. Bentele, Öffentliches Vertrauen: Normative und soziale Grundlage für Public Relations, Opladen: Springer, 1994.

Credibility is a sub-phenomenon trust, and the term is limited to communication. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. Bentele (1988) defines credibility as a quality which is attributed to individuals, institutions, or their communicative products (oral or written texts, audio-visual displays) by someone in relation to something (events, facts)”. 44G. Bentele, Der Faktor Glaubwürdigkeit: Forschungsergebnisse und Fragen für die Sozialisationsperspektive, 33(2/3) ed., vol. Publizistik, 1988, p. 406–426. Therefore, credibility is not to be considered as an intrinsic property of objects or persons, but as a relational property. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

The Deutsche Telekom is assessed to be successful in gaining credibility with regard to sustainability issues. Telekom’s reserved way of communicating its commitment to sustainability is perceived by the firm’s stakeholders as more convincing, honest, and credible than the efforts of other companies, which are often accompanied by massive communication measures. The messages of the firm’s sustainability commitment are successfully designed: the use of appealing motifs creates the necessary emotionality, information and explanations ensure the right degree of rationality, and communication, which not only reports achievements and successes, but also covers the path and efforts the company has taken to achieve sustainability, conveys credibility. 16F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unternehmenskommunikation. Bedeutung, Charakteristika und Herausforderungen, Wiesbaden: Gabler, 2010., 40F. Brugger, Nachhaltigkeit in der Unernehmenskommunikation, 2016.

Best Practice: Telekom AG

3.1.5 Storytelling

Storytelling refers to communication in terms of stories told by companies while using a social constructivist perspective. This kind of communication used for CSR affairs is related to concepts of narrativity, storytelling, sensemaking and sensegiving. It can be understood as a social narrative developed through the stories of different actors such as individuals, corporations, media, public, NGOs etc. Corporate storytelling is often a discourse of different stories about the company that can be put into societal narratives. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

British Petroleum (BP) started an international campaign in 2000 with the aim to rebrand its image into a socially and ecologically responsible corporation. Starting the campaign, a new logo was introduced and information about its action on climate change were released. The main content of the campaign was a television spot. The story is about a reformed sinner that expresses hope for a better future. In only 50 seconds, more than ten different and problematic areas of life are shown and immediate solutions for them are presented. At the end of the spot, BP placed some vibrant image by showing how someone drives through a dark tunnel which signalizes the way from sin to purity. When the end of the tunnel is reached, the driver reaches purity which is presented by the logo of BP. As the spot does not show exactly how BP will reach the goals itself, it released another series of spots that explain how the company wants to reduce carbon emissions. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

Best Practice: British Petroleum

3.2. Communication tools

There are many tools for companies to communicate their sustainability efforts. It is possible to divide the tools into internal and external ways of communication. Several communication channels can be used at the same time, but when doing so it is important to employ the right combination. The presented tools are similar to tools used in CSR affairs and PR. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014., 41M. Allen, Strategic Communication for Sustainable Organizations: Theory and Practice, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer, 2016.

3.2.1 Online communication

Communicating online on the internet has become a vital tool to put information into the world. The internet bears challenges and opportunities at the same time. On the one hand, stakeholders can publicly always discuss their demands on companies and therefore, build up pressure. On the other hand, companies can use it as a communication channel. This can be done actively or passively. In the case of the latter, the Internet can be used to observe, identify, and evaluate stakeholder demands and expectations regarding company affairs. If used actively, companies can use the Internet to inform their stakeholders, enter into a dialog with them and thus, shape a relationship. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114.

When engaging in online communication, it is crucial to have a central starting point for the topic in question on the internet: a separate section on sustainability on the corporate website or a separate campaign website for specific campaigns or actions should be embedded. The corporate website should represent the company’s overall commitment in a concise way and further explain why the company is involved in the topic. Users should be able to access material and information quickly and easily. From the company or campaign website, all other channels should be easily accessible, for example: subscription option to a newsletter if available, connection to the corporate blog, connection button to social media networks like Facebook, XING, Twitter or YouTube and a connection to the section on sustainability or the campaign website where the user can perform actions like voting, donating, discussing, or sharing content. The separate campaign website is a simple method of information transfer for both website visitors and the company. It enables visitors to access the information they want conveniently and without any delay. At the same time, it enables the company to inform its target groups and prevents scattering loss. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114.

Patagonia is a clothing company for outdoor clothing and gear. The clothing company sells its products online via its website and in stores. On the website, a seperate shop section can be found to access the products for men and women with respect to different sports. Specific sections for ‘Activism’, ‘Stories’, and ‘Company’ are embedded into the corporate website making it easy for users to access company information regarding their sustainability actions. The section on ‘Activism’ provides information on how customers can take action by providing a platform on how to find organziations to fund or petitions to sign. This way Patagonia provides an easy accessable platform for its customers to start participating in sustainability affairs. The company section provides information on their climate goals, footprint, corporate responsbility and their sustainable business model so the customers are able to access company information convenionetly. The section ‘Stories’ provides specific stories on sports, culture and planet from people that were interviewed and accompanied by Patagonia in their own trips or missions. 45“Patagonia,” [Online]. Available: www.patagonia.com/home/. [Accessed 13 09 2022].

Best Practice: Patagonia

Social Media is a tool that companies can use to address target groups that they find difficult or impossible to reach through traditional information channels. Corporations can use social media networks to present projects, report about successes or show related pictures. In addition, interested users can participate in the sustainability affairs directly. This creates new opportunities and challenges for companies. The internet enables different stakeholder groups to build up a relationship with the company and put specific issues on the corporate agenda. Companies should see this development as an opportunity for interaction and use it as direct feedback from stakeholders. Due to the large number of existing networks, communicating through social media should be carefully embedded in the overall communication strategy as each network has different target groups. Another communication channel are podcast and video platforms that have potential to convey corporate messages to its stakeholders quickly, personally and with minimal scattering loss. Podcasts and videos can be produced on any topic and can serve an informational purpose or entertainment. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114.

The Ecosia podcasts provide stories from all around the world with updates on Ecosia itself and its reforestation projects. Also, conversations with environmentalist, personal stories and facts are part of the podcast series making it easy for all kinds of stakeholders to get the most updated information on Ecosia. 46“Ecosia Blog,” [Online]. Available: blog.ecosia.org/tag/podcast/. [Accessed 13 09 2022].

Best Practice: The Ecosia Podcasts

An example for an internal online communication tool is the intranet which is an information and communication platform for employees to bundle all company’s information, processes and applications on a common and uniform interface, making these accessible at any time, location, and on various output devices. This simplifies the flow of information and everyday work within the company, but most importantly enables the establishment of an open communication culture within a company. 47comundus GmbH, Vom Intranet zum Mitarbeiterportal, Stuttgart, 2013.

3.2.2 Analogue communication: Personal communication and events

Despite all technical options, companies must communicate their agenda and affairs through personal communication, which remains the key to a functioning company. 48S. Grupe, Public Relations: Ein Wegweiser für die PR-Praxis, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2011. Personal communication refers to the planning, organization, execution, and control of all activities based on a face-to-face communication used by a company towards its internal and external stakeholders. 49M. Bruhn, Kommunikationspolitik: Grundlagen der Unternehmenskommunikation, München: Vahlen, 1997. Through personal communication questions, criticism, or incentives can be addressed and joint approaches to solve problems can be found in direct conversations. In addition to factual input, personal communication also conveys emotionality and authenticity which makes it possible to experience the essence of a company. Personal communication can strengthen relationships, develop team spirit, and build trust. This form of communication is challenging as it is quite time-consuming: people must be gathered in one place, events must be well organized, and discussions prepared so that the desired effect can be achieved. An important task of personal communication is the leadership of employees, especially when it comes to fundamental strategies and change processes in the company. Communicating changes in person can provide explanations, clarify, convince, motivate, and mobilize. When initiatives or projects are started to initiate changes, employees must be convinced. If they are to play an active role in the shaping processes, the most effective way is personal contact. 48S. Grupe, Public Relations: Ein Wegweiser für die PR-Praxis, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2011.

One way to implement regular personal contact is the establishment of a team-briefing-structure. Team-briefings ensure the functioning of the information exchange from the company management to employees via all company levels, meaning the passing of it from top to bottom level. Moreover, it makes the collection and channelling of questions, criticism, ideas, and suggestions from the bottom to the top level possible. 48S. Grupe, Public Relations: Ein Wegweiser für die PR-Praxis, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2011. Another way to reach a strong employee participation in order to initiate changes is to introduce task forces, conduct inhouse training or employee workshops. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114., 50B. Lühmann, Entwicklung eines Nachhaltigkeitskommunikationskonzepts für Unternehmen, Lüneburg, 2003. This facilitates knowledge transfer between employees with different qualifications, the activation of innovation potentials, the generation of motivation, and lastly the consciousness of co-workers regarding their joint responsibility in the context of the cooperate performance can be awakened. 51W. Hopfenbeck and M. Willig, Umweltorientiertes Personalmanagement. Umweltbildung, Motivation, Mitarbeiterkommunikation, Landsberg/Lech: Moderne Industrie, 1995.

In 2006, the Deutsche Post DHL, global logistics provider, started its GoGreen initiative, committing to improving its carbon dioxide efficiency by 30 % by 2020. The strategy to achieve the goal included fleet optimization, and offering carbon-neutral, climate-friendly products and services. To achieve the goal, it was actively communicated to the employees. Employees were encouraged to get involved and had the possibility to put in their own ideas on how the company could perform better. Moreover, success stories and GoGreen messages were incorporated into DHL’s morning briefings, to generate and sustain involvement and initiatives. Further, GoGreen boards were installed at prominent locations in all DHL Express’ AP facilities, displaying developments in the program, the monthly energy consumption and carbon emission reduction in the facilities. By this, the hardly tangible was made visible, enabling the employees to track and monitor their progress with the GoGreen goals. Being able to compare with other facilities – which fostered friendly competition – and see how each change made, spurred further GoGreen efforts. 52A. Yang, DHL Express Asia Pacific: Going Green, The Case Centre, 2012.

Best Practice: DHL Express Asia Pacific

Changes must be communicated also externally to all relevant stakeholders and interested parties. In this case, personal communication is an effective way as well. Since stakeholder expectations and demands are vital to a cooperation, a long-term and permanent dialog based on trust must be established with all relevant stakeholder groups. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114. This can be done for instance via stakeholder dialogues to exchange ideas, identify critical topics, and discuss these as they may be decisive for the corporate strategy at some point. Another option is a dialog forum which is a cooperate event that brings together representative of stakeholder groups. The aim is that stakeholders contribute both their outside view of the company’s system and the own interests and demands of the respective group. When selecting relevant stakeholders, the entire corporate environment should be taken into account. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114.

Events, expert discussions, trade fairs, panel discussions, conferences and events that are not initiated and organized by the company itself are also suitable communication platforms. By participating in trade fairs, panel discussions, conferences, or expert talks on various topics relevant to CSR, companies can promote dialog and build trust. Image improvement, contact cultivation, and, especially at trade fairs, the presentation of new products and services are further positive effects. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114.

Another useful opportunity to establish contact with various stakeholder groups, strengthen relationships, and communicate CSR issues in an informal atmosphere are open days. Through personal contact, these events offer opportunities for the company to learn about and reduce visitors’ misunderstandings, uncertainties and fears, and to build trust through respectability. An open day can make a positive contribution to image improvement if conducted well. 53D. E. Crews, Strategies for Implementing Sustainability: Five Leadership Challenges, Texas: SAM Advanced Management Journal, 2010.

A pioneer in the field of sustainability is consumer goods manufacturer Henkel, which was one of the first German companies to implement a sustainability strategy. Henkel conducts face-to-face meetings with representatives of local institutions and organizations as well as larger information events. For example, once a year, the communications team organizes an open day, where the public can gain an insight into the production facilities. In the direct dialogue Henkel gains valuable information and insights – from complaints and suggestions for improvement to questions, contact requests and ideas for cooperation – from residents and other stakeholder groups. 12M. Hillmann, Das 1×1 der Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Wegweiser Für Die Praxis, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2017.

Best Practice: Henkel

3.2.3 Reporting

Another channel for CSC is corporate reporting to external stakeholders. It is a comprehensive and annually repeated process in which information beyond financial reporting is presented. The focus here is on non-financial information on environmental as well as social issues, such as respect for human rights and the fight against corruption. Reporting includes the establishment of a risk management system and the measurement of progress against performance indicators. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020. As a prerequisite, management must see the reporting as relevant to control and the corresponding resources (time and financial framework) must be made available. 53D. E. Crews, Strategies for Implementing Sustainability: Five Leadership Challenges, Texas: SAM Advanced Management Journal, 2010. The content of sustainability reporting must be quantitatively measurable using performance indicators and needs to include retrospective and prospective information. To this end, companies must establish and integrate processes and management systems that serve to gather data and are tailored to the individual concerns of stakeholders. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020.

The process of sustainability reporting is regulated by legislators by means of directives and regulations. With the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) of April 21, 2021, the European Commission has presented a draft directive that further develops the previous EU directive on non-financial reporting (NFRD, Directive 2014/95/EU) and thus expands and standardizes reporting within the EU. 54Council of the European Union, “Directive amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as regards corporate sustainability reporting General approach,” 2022. The draft CSRD applies to new size criteria, of which at least two must be present in order to fall within the scope: an annual average of more than 250 employees, a balance sheet total of 20 million and sales of 40 million euros. 55Council of European Union, “Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Directive 2013/34/EU, Directive 2004/109/EC, Directive 2006/43/EC and Regulation (EU) No 537/2014, as regards corporate sustainability,” 2021. The CSRD is intended to ensure that companies report on environmental, social, and governance factors linked to their business activities in their management reports in the future. 56Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union, “Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2020/1816 of 17 July 2020 supplementing Regulation (EU) 2016/1011 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the explanation in the benchmark statement of how environmental, social and governance factors,” 2020.

In the case of external sustainability reporting, which involves implementing sustainability in strategy based on sustainability targets and measuring them using key performance indicators, companies have so far been able to decide whether to produce a separate sustainability report, published for example as a print or online edition, or to integrate sustainability performance into an existing medium. For this purpose, the management report is often used in the annual report (integrated reporting) and the non-financial statement is presented in a separate section of the management report or fully integrated in different parts of the management report. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020. This creates the possibility to show financial and non-financial key figures together in one report and to include the sustainable development of a company in existing management systems, such as the environmental management system Eco Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS). 57M. S. Fifka, “CSR und Reporting,” Springer Gabler Berlin, Berlin, 2014.

With the implementation of the CSRD, a combined report consisting of a financial report and a sustainability report (part of the management report) becomes mandatory. The content and formal requirements of legally mandatory reporting influence the overarching strategy and corporate governance and thus form the basis and central pillar for CSC. The legally regulated and standardized reporting simplifies the comparison between companies for stakeholders, rating agencies and investors. 29K. Mayer, Sustainability: 125 Questions and Answers, Guide to the Economy of the Future, Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2020.

Also info brochures, employee newspapers, newsletters, and message boards are reporting tools that companies can utilize in order to provide information to the public, politicians, customers, suppliers, authorities, the media and other actors. 42P. Heinrich, CSR-Kommunikation – Die Instrumente, Ingolstadt: Springer-Verlag, 2018, pp. 87-114.

3.2.4 Further tools of communication

In addition to the above-mentioned communication tools, there are further ways to engage in communication internally and externally. For example, professional media relations is another way to inform stakeholders about company activities. Examples of professional media relations are professional articles, press conferences, interviews, editorial visits, and media. In practice, many companies begin by strategically incorporating their CSR activities into their media relations. Carefully planned and executed, it can be a useful first step in CSC. After all, a company’s reputation is still largely formed by the mass media, i.e., the press, radio and television, and the internet, including social media. Therefore, professional media relations are also a very effective field of action for CSC. It has an impact both externally, but also internally, as the company’s employees are also recipients of the mass media. 46“Ecosia Blog,” [Online]. Available: blog.ecosia.org/tag/podcast/. [Accessed 13 09 2022].

4 Drivers and barriers

Every company is embedded in an environment that influences the company to a considerable extent, which at the same time is influenced by the company. 58R. M. Schomaker and A. Sitter, “Die PESTEL-Analyse – Status quo und innovative Anpassungen,” Der Betriebswirt, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 3-21, 2020. Therefore, the successful implementation of CSC in business practice can be influenced by a variety of factors, both facilitating and hindering it. From the company’s perspective, these can be divided into internal and external factors, which will be presented in detail in the following sections for drivers as well as for barriers. At the end of the chapter on barriers, general strategies and a selected best practice example are provided on how barriers can be successfully overcome.

4.1 External drivers

To analyze the macro-environment of a company in general and to derive potential developments as well as future opportunities and risks, the application of the PESTEL analysis represents a suitable method. 58R. M. Schomaker and A. Sitter, “Die PESTEL-Analyse – Status quo und innovative Anpassungen,” Der Betriebswirt, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 3-21, 2020. Hence, it is also well suited for systematically identifying the external drivers of CSC and interpreting their influence. The individual segments of the PESTEL analysis, i.e., political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal, form the framework for the following explanations.

When examining the political factors of influence, it is important to distinguish between the international, supranational, and national levels. Every company is affected by all three levels, but to varying degrees, depending on the legal form chosen and the sector in which it operates, among other things. 58R. M. Schomaker and A. Sitter, “Die PESTEL-Analyse – Status quo und innovative Anpassungen,” Der Betriebswirt, vol. 61, no. 1, pp. 3-21, 2020. The European Green Deal, which was presented by the European Commission on December 11, 2019, is a concept that pursues the goal of reducing net emissions of greenhouse gases in the European Union to zero by 2050, thus becoming the first “continent” to become climate neutral. 59European Commission, “Der europäische Grüne Deal,” 11 Dezember 2019. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/european-green-deal-communication_de.pdf. [Accessed 10 September 2022]. As an interim target for 2030, European leaders agreed in December 2020 to the Commission’s proposal to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% compared to 1990 levels. 60European Commission, “Delivering the European Green Deal,” 14 July 2021. [Online]. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal_en#documents. [Accessed 10 September 2022]. At the German level, the implications of the above-mentioned European targets are reflected in the coalition agreement of the current German government from 2021. The German government aims to align its climate, energy, and economic policies with the 1.5-degree path and achieve climate neutrality by 2045 at the latest. 61Bundesregierung, “Mehr Fortschritt wagen,” 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/974430/1990812/04221173eef9a6720059cc353d759a2b/2021-12-10-koav2021-data.pdf?download=1. [Accessed 9 September 2022]. Hence, at the political level, in Europe and Germany the conditions are in place to promote sustainable action by companies and thus also to facilitate communication about it. Crucially, governments need to be aware of and adhere to the accepted principles and CSR standards of their respective communities, which change dynamically over time. If they succeed in doing so, they can positively influence CSR development through active CSC with companies. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

On the economic level, sustainable products and services form a promising (new) sales market for companies, as demand for them is generally increasing. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. Hence, economic goals, such as marketing goals, cost savings through efficiency increases and the fulfilment of customer and shareholder wishes, which can generate increases in sales and profits, can also be achieved with CSC. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007. Transparent communication of these economic objectives as part of a CSR strategy also offers companies the opportunity to build stronger, long-term relationships with their (strategically important) stakeholders. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

The public’s expectations of CSR can be described as a social construct in transition, which ensures that companies must maintain a dialogue with their stakeholders and constantly update their communication strategy if they are to continue to meet expectations. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. In this context, global and local climate movements such as Fridays for Future, Extinction Rebellion, Letzte Generation, and Ende Gelände have played an increasingly important role in recent years, as they have shaped social discourse and thus also influenced election results (European elections 2019, German federal elections 2021) and political decisions. From the company’s perspective, these changing societal expectations are a driver for CSC, as they can have a direct impact on the company’s image. If the expectations are met through appropriate CSR measures and the corresponding CSC, this leads to sympathy. If this is not the case, it leads to antipathy. 62M. Schwaiger, “Components and parameters of corporate reputation: An empirical study,” Schmalenbach Business Review, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 46-71, 2004.

In terms of technology, the (advancing) digitization of communications is a driver for CSC. As a result, news and information are shared much faster globally, so that companies also must react to this more quickly. This is increasingly evident on social media channels, where the millions of users worldwide ensure rapid distribution by sharing the news themselves. It is therefore not a sensible decision for companies to not communicate about their CSR issues themselves. Either the information deliberately sent by the company is shared or it is shared that the company does not or not sufficiently address the relevant CSR topics. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

To assess the current environmental impacts on CSC, an analysis of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reports is well suited. In its sixth report, published at the beginning of this year, the IPCC again makes clear that the global temperature rise is due to increasing anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Furthermore, the IPCC informs that the remaining carbon budget, which can probably limit the global temperature increase to 1.5 degrees Celsius, will be exhausted before 2030, if global CO2 emissions continue as they are now. Hence, from an ecological point of view, there is an urgent need for corporate sustainable behaviour and for CSC. 63IPCC, “Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change,” Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2022., 64IPCC, “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs),” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6wg3/pdf/IPCC_AR6_WGIII_FAQ_Chapter_02.pdf. [Accessed 9 September 2022].

In the legal sense, it is primarily the more comprehensive sustainability reporting requirements on the part of the EU that directly drive the CSC (see chapter 3.2.3).

4.2 Internal drivers

For the investigation of CSC’s internal drivers, employees in particular play an essential role, since as internal stakeholders they have a direct influence on the company’s communication and at the same time are directly influenced by the communication that originates from the company. In addition, communication with suppliers is relevant, as is communication with a possible works council and possible subsidiaries.

In general, a distinction can be made in internal communication between formal and informal communication. The formal variant comprises all official communication channels and instruments of the company that are used for successful internal communication. Personal, cross-team or cross-departmental exchange processes, on the other hand, which are not controlled by the company and are often also referred to as “hallway chatter,” constitute informal internal communication. The drivers for CSC apply in principle to both communication variants and are embodied above all by the achievement of the following goals: the transfer of information and knowledge of the CSR strategy and (planned) measures, equal dialog among employees and between employees and managers, and the motivation and retention of employees. There is a strong interaction between these three goals, so that the effects of individual actions should always keep in mind the changes in all three goals. If this is successful, it can result in a strong internal driver for CSC, powered by both employees and managers. 65R. Klein, “Interne Kommunikation als Teil der Unternehmenskommunikation,” Passion4Business GmbH, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.fuer-gruender.de/wissen/unternehmen-gruenden/aussenauftritt/interne-kommunikation/. [Accessed 2 September 2022].

4.3 External barriers

The PESTEL analysis can also be used to examine the external barriers of the CSC, resulting in a comparison of the external drivers and barriers. At the EU level, recent changes to the EU taxonomy, which is an instrument of the EU Green Deal, represent the biggest political barrier to CSC. The EU taxonomy generally aims to set a clear framework for classifying economic activities and consequently financial instruments as “green” and “sustainable”. 66European Commission, “EU taxonomy for sustainable activities,” 2022. [Online]. Available: https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en. [Accessed 3 September 2022]. On 06.07.2022, the EU Parliament did not reject the delegated act of the EU Commission, containing the proposal to classify certain natural gas and nuclear power activities as “sustainable” and therefore to include them in the EU taxonomy. 67European Parliament, “Taxonomy: MEPs do not object to inclusion of gas and nuclear activities,” 6 July 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220701IPR34365/taxonomy-meps-do-not-object-to-inclusion-of-gas-and-nuclear-activities. [Accessed 12 September 2022]. As things stand today, this will happen on 01.01.2023, thus from this date investments in gas and nuclear power plants will also be possible via “sustainable financial instruments”. The war in Ukraine started by Russia has also led to an energy crisis in Europe in 2022. As a result, an energy security law was approved by the German Bundestag and Bundesrat in July 2022, which provides for reactivating coal-fired power plants from reserve for electricity generation to save gas (limited until March 2024). Furthermore, the political debate on the extended use of nuclear power plants has been reignited in Germany over the legally agreed shutdown at the end of this year. The German government’s proposal envisages the continued operation of two (of the three currently still running) nuclear power plants in reserve mode until the end of April 2023 at the latest, to be able to compensate for any shortage of electricity over the winter. 68M. Kreutzfeldt, “Längere Laufzeit nur im Notfall,” taz Verlags u. Vertriebs GmbH, 5 September 2022. [Online]. Available: https://taz.de/Energieversorgung/!5879133/. [Accessed 10 September 2022]. Overall, the two described policy developments at the EU level and at the German level are to be seen as obstacles for CSC, as they dilute the notion of sustainable investments (EU taxonomy) and put the short-term focus on the increased use of coal and nuclear power plants instead of the expansion of renewable energies (decisions of the German government).

In the economic sphere, the biggest problem for CSC is that long-term thinking is not a habit for both companies and stakeholders. However, this long-term thinking is a prerequisite for seriously transforming (existing) business models in terms of socio-ecological sustainability, as this transformation requires patience from all stakeholders for most CSR measures to pay off economically in the mid- and long-term. Focusing purely on short-term profits is therefore a major economic obstacle for CSC. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007.

When company representatives discuss their CSR goals and measures with their stakeholders, the latter tend to react negatively at first. This is due, on the one hand, to the short-term profit orientation of some stakeholders described above and, on the other hand, to the lack of sustainability reputation of the companies in some cases. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. Overall, sustainability issues are very complex because they influence each other systemically and are therefore practically impossible to solve individually. This results in conflicting goals for companies, which in turn can lead to dissatisfied stakeholders. In the end, these can lead to credibility problems for the company, thus closing the circle to the negative initial reaction of the stakeholders discussed at the beginning. 15B. Signitzer and A. Prexl, “Corporate Sustainability Communications: Aspects of Theory and Professionalization,” Journal of public relations research, vol. 1, pp. 1-19, 2007.

The digitization of communication is constantly creating new communication channels and trends, with stakeholders generally expecting the company to always communicate with them in the most up-to-date way. This means that the communicating employees not only have to know the latest channels, but also must convey the content in the way that their stakeholders want. This can quickly become too much for those responsible, which is a hurdle for CSC that arises from the company’s technical environment. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.

The epistemic status of the climate poses a major communication challenge. The IPCC defines climate as “the statistical description in terms of the mean and variability of relevant quantities over a period of time ranging from months to thousands or millions of years” 69IPCC, “Glossary of Terms,” in Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaption, Cambridge , Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 555-564.. Weather, on the other hand, is defined by a short-term condition of the air and atmosphere at a particular time in a particular place. Variable and measurable conditions such as temperature, humidity, precipitation, barometric pressure, and wind strength are used for this purpose. Climate, unlike weather, can thus neither be seen, heard, nor felt by humans. Hence, the visibility of global climate change is not simply a given, but must be constructed and communicated, which is a challenge for successful CSC. 69IPCC, “Glossary of Terms,” in Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaption, Cambridge , Cambridge University Press, 2012, pp. 555-564.

The laws, regulations, and standards currently in force are not compatible with the Paris climate targets, neither at the European nor at the German level. As a result, the barrier to CSC from the environmental law environment is that entrepreneurial action that is in line with the Paris climate goals is made more difficult. This is caused by the fact that the legal situation overall makes climate-damaging behavior (e.g., through subsidies for fossil fuels) financially more attractive than climate-friendly behavior. 70SZ, “Unternehmen der G7-Länder weit weg von Pariser Klimazielen,” Süddeutsche Zeitung GmbH, 6 September 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.sueddeutsche.de/wissen/klima-unternehmen-der-g7-laender-weit-weg-von-pariser-klimazielen-dpa.urn-newsml-dpa-com-20090101-220906-99-644782. [Accessed 10 September 2022].

4.4 Internal barriers

The internal barriers to CSC listed as follows relate to the internal drivers described above and can also be seen as their opposite effects. If internal CSC is carried out too late, not transparently or only unilaterally, this results in a barrier to successful CSC, as it is almost impossible for employees to compensate for these omissions on their own at the right time and with the appropriate content. Another internal hurdle for CSC is when employees and their (communication) ideas do not receive adequate appreciation and attention within the company. Among other things, this can also be related to the wrong choice of communication channels, which is a third internal barrier for CSC. Should the company engage in greenwashing instead of ethically motivated CSR strategies and measures, credible CSC cannot be sustained either internally or externally in the medium and long term. 65R. Klein, “Interne Kommunikation als Teil der Unternehmenskommunikation,” Passion4Business GmbH, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.fuer-gruender.de/wissen/unternehmen-gruenden/aussenauftritt/interne-kommunikation/. [Accessed 2 September 2022].

4.5 Actions to overcome barriers of CSC

The actions listed below are generally appropriate for overcoming both the internal and external barriers to CSC, as there is a strong interaction between the two levels, which is targeted by the actions. To improve the reputation of a company, it must align its CSC with its CSR actions, because these two are interrelated and co-construct each other. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014. In other words, CSC can support sustainable corporate management, but cannot replace it. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020.

Therefore, a key action to overcome CSC’s obstacles is for management to develop a CSR strategy that is intrinsically motivated and adapted to the specifics of the company. Strongly linked to this is the recommendation to bring internal stakeholders (i.e., primarily employees) on board early in the planning and implementation of CSR and CSC, as they can then serve as an additional channel for communicating the initiatives with external stakeholders. 71W. T. Coombs and S. J. Holladay, Managing Corporate Social Responsibility, Chichester : John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2012.

In addition, the fundamental choice of orientation in corporate communications is crucial. For overcoming the hurdles for CSC described above, output-oriented communication is better suited than input-oriented communication, since the former assumes permeability and overlap between society and the company, while the latter views them as two separate systems. The stakeholder approach also fits in with the output orientation, as it focuses on transparency, dialogue and participation between the company and its stakeholders, and also emphasizes the great importance of the communication relationships between these two. 5C. Mast, Unternehmenskommunikation: Ein Leitfaden, München: UVK Verlag: Narr Francke Attempto Verlag, 2020.

Since communication about a CSR initiative can also cause negative reactions from stakeholders and thus do more harm than good, it is important to recognize signs of a backlash early on so that necessary corrections can be made to the communication plan. 71W. T. Coombs and S. J. Holladay, Managing Corporate Social Responsibility, Chichester : John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2012. A good way to respond to such setbacks, or ideally to avoid them from the outset, is to apply SMART messaging. According to this, ideally, all messages sent by the company should be strategic, memorable, accurate, relevant, and trustworthy. 41M. Allen, Strategic Communication for Sustainable Organizations: Theory and Practice, Heidelberg, New York, Dordrecht, London: Springer, 2016. In corporate practice, this is probably not feasible for every message, but it makes a lot of sense for all employees to internalize these five attributes for their communications and to review their implementation continuously critically.

In summary, serious CSC with all stakeholders enables ethical and moral CSR actions, and at the same time, ethical and moral motivation for CSR actions is a prerequisite for credible CSC with all stakeholders. 14Ø. Ihlen, J. Bartlett and S. May, The handbook of communication and corporate social responsibility, Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014.