Authors: Carla Belau, Melusine Münch, Jana Schröer

Last updated: October 1st 2023

1 Relevance

Globally, social and economic systems are colliding with earth system boundaries.1 Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102-111 (2023). According to the latest article by Rockström et al. (2023) “seven out of eight globally quantified earth system boundaries have been crossed […] putting human livelihoods for current and future generations at risk”1 Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102-111 (2023). . The changes that are destabilizing the earth system are primarily fueled by unsustainable resource extraction and consumption patterns rooted in current social and economic systems. The pursuit of economic growth has not only been associated with rising greenhouse gas emission levels, material use and other environmental impacts, but also with increasing social inequality.2 Haberl, H. et al. A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environmental Research Letters 15 (6), 1-42 (2020). 3 Paulson, L. & Büchs, M. Public acceptance of post-growth: Factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures 143, 1-15 (2022). Deprioritizing economic growth and the associated increase in gross domestic product (GDP) as a political objective is thus supported by a growing number of academics and organizations.4 Jackson, T. Prosperity without growth. Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Second Edition. (Routledge, 2017). 5 Kallis, G., Kerschner, C. & Martinez-Alier, J. The economics of degrowth. Ecological Economics 84, 172-180 (2012). 6 Jensen, L. Beyond Growth. Pathways towards sustainable prosperity in the EU. European Parliamentary Research Service. (2023). 7 Paech, N. Befreiung vom Überfluss. Auf dem Weg in die Postwachstumsökonomie. (Oekom Verlag, 2012). The core assumption is that to avoid an acceleration of the environmental and social crises, it is necessary to reframe current economic thinking so that the focus is shifted on improving social welfare within planetary boundaries.8 Hardt, L., Barrett, J., Taylor, P. & Foxon, T. What structural change is needed for a post-growth economy: A framework of analysis and empirical evidence. Ecological Economics 179, 1-13 (2021). 9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization, 28 (3), 380-404 (2021).

2 Definition and Delimitation of Concepts

2.1 Postgrowth

Postgrowth is an umbrella term for concepts and approaches that challenge the current economic thinking and advocate moving beyond the paradigm of unlimited economic growth.3 Paulson, L. & Büchs, M. Public acceptance of post-growth: Factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures 143, 1-15 (2022). 10 Kopfmüller, J. & Nierling, L. Postwachstumsökonomie und nachhaltige Entwicklung – Zwei (un)vereinbare Ideen? Technikfolgenabschätzung – Theorie und Praxis, 25 (2), 45-54 (2016). Instead, the broad unifying vision of an economy and society that prioritizes social and environmental wellbeing is being pursued.11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). Postgrowth can be distinguished from the concept of green growth, which assumes that the reduction of environmental impacts and the achievement of social objective is in line with the goal of continuous economic growth.12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022).

Postgrowth futures are widely defined and differ in their strategy for change, their relationship to capitalism as well as their perception of the role of the state. Postgrowth ideas provide a wide scope of approaches to transition that ranges from rather reformist to more radical positions.11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). 13 Wiedmann, T., Lenzen, M., Keyßer, L. & Steinberger, J. Scientists‘ warning on affluence. Nature communications 11 (1), 1-10 (2020). Reformist approaches advocate that the required transformation is achievable within the current structure of the market economy and centralized democratic states, even though fundamental reforms would be necessary to deprioritize economic growth. Representatives of this position may also share agnostic growth or a-growth ideas, suggesting abandoning the growth discourse altogether and shifting away the focus to other objectives of social welfare.12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022). 14 van den Bergh, J. Environment versus growth – A criticism of “degrowth” and a plea for “a-growth”. Ecological Economics 70 (5), 881-890 (2011). 15 Evroux, C., Spinaci, S. & Widuto, A. From growth to beyond growth: Concepts and challenges. European Parliamentary Research Service. (2023). Approaches that are more radical regard today’s capitalism as not compatible with a postgrowth economy and aim instead at differently organized forms of production.13 Wiedmann, T., Lenzen, M., Keyßer, L. & Steinberger, J. Scientists‘ warning on affluence. Nature communications 11 (1), 1-10 (2020). 16 Alexander, S. & Rutherford, J. The Deep Green Alternative. Debating Strategies of Transition. Simplicity Institute Report 14a. (2014). However, opinions differ on whether the democratic state plays an important role in the socio-ecological transformation or a shift beyond centralized states is required.

Nevertheless, various similarities between the different approaches can be identified. It is generally agreed that material throughput shall be kept within the planetary boundaries and natural ecosystems provide a framework for human activity.3 Paulson, L. & Büchs, M. Public acceptance of post-growth: Factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures 143, 1-15 (2022). 10 Kopfmüller, J. & Nierling, L. Postwachstumsökonomie und nachhaltige Entwicklung – Zwei (un)vereinbare Ideen? Technikfolgenabschätzung – Theorie und Praxis, 25 (2), 45-54 (2016). Moreover, alongside a greater focus on social objectives, changes towards the redistribution of wealth and income and decreasing inequality are of high importance. Another common point of view is that a reorientation towards more appropriate welfare measures than GDP is necessary.

2.2 Degrowth

Degrowth represents a more concrete approach under the postgrowth umbrella.3 Paulson, L. & Büchs, M. Public acceptance of post-growth: Factors and implications for post-growth strategy. Futures 143, 1-15 (2022). It serves as a normative concept that criticizes the dominant paradigm of economic growth and provides an overarching vision from which analytical and practical applications can be drawn.17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). At its core, degrowth can be defined as a “process of political and social transformation that reduces a society’s throughput while improving the quality of life”17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). , with throughput referring to the material and energy flows in and out of an economy. The underlying assumptions are that growth is unsustainable and human progress without economic growth is possible.18 Schneider, F., Kallis, G. & Martinez-Alier, J. Crisis or opportunity? Economic degrowth for social equity and ecological sustainability. Introduction to this special issue. Journal of Cleaner Production 18. (1), 511-518 (2010). Degrowth advocates pursue the objective of a degrown steady-state economy ensuring well-being, ecological sustainability and social equity.5 Kallis, G., Kerschner, C. & Martinez-Alier, J. The economics of degrowth. Ecological Economics 84, 172-180 (2012). 18 Schneider, F., Kallis, G. & Martinez-Alier, J. Crisis or opportunity? Economic degrowth for social equity and ecological sustainability. Introduction to this special issue. Journal of Cleaner Production 18. (1), 511-518 (2010). 19 O’Neill, D. Measuring progress in the degrowth transition to a steady state economy. Ecological Economics 84, 221-231 (2012). Degrowth can thus be viewed as a transitory phase leading to a lower steady state, mostly applying to economies in the global North. A reduction in the society’s throughput will lead to economic degrowth, as degrowth scholars view a sufficient decoupling of economic growth from throughput as highly unlikely due to rebound effects and a lack of quantitative evidence.17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). 20 Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics 70 (5), 873-880 (2011). This sustainable degrowth will most likely result in a decrease in GDP, but GDP degrowth is not the objective per se.

Degrowth is a concept that recognizes the need for systemic political, institutional and cultural changeand can thus be viewed as a rather radical postgrowth approach.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). Most advocates view capitalism as not compatible with the idea of degrowth, and thus a transformation towards a different system is needed to ensure “a prosperous way down”23 Odum, H. & Odum, E. The prosperous way down. Energy 31 (1), 21-32 (2006). and avoid unsustainable degrowth in the form of economic recessions with deteriorations of social conditions.18 Schneider, F., Kallis, G. & Martinez-Alier, J. Crisis or opportunity? Economic degrowth for social equity and ecological sustainability. Introduction to this special issue. Journal of Cleaner Production 18. (1), 511-518 (2010).

As a movement, degrowth (décroissance) has been coined in the early 2000s by French activists protesting, amongst others, for a car- and ad-free city, which also mobilized activists in other European countries and beyond.24 A History of Degrowth. Degrowth Info. https://degrowth.info/en/history (2023). The term was derived from the title of a collection of essays written in the 1970s and 80s by physicist-economist Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen.25 Georgescu-Roegen, N. From Bioeconomics to Degrowth: Georgescu-Roegen’s New Economics in Eight Essays. (Routledge, 2011). The impulse towards degrowth also stemmed from modern scholars including French economist Serge Latouche (2009)26 Latouche S. Farewell to Growth. (Polity Press, 2009). criticizing the ideology of economic development. In 2008, the first international degrowth conference took place in Paris, bringing together a community of scholar-activists studying and practicing degrowth.17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). 27 A History of Degrowth. Degrowth Info. https://degrowth.info/en/history (2023).

3 Literature Review

3.1 The Growth Paradigm

3.1.1 Origin and Evolution of the Growth Paradigm

Before the 19th century, in the pre-capitalist era, the term economic growth was not used at all.12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022). A rising population was not connected to economic output and activity, and rather seen as a constraint to this output and activity. In the 19th century, a growing economic output was seen as the natural outcome of capitalist production and commerce. In the beginning of that century, there was an unprecedented rise in population and economic activity and economic growth even outpaced population growth due to new technologies enabling labor productivity to increase. In the 20th century, the term ‘economic growth’ began to be used. Lots of countries industrialized leading to growing economies and falling poverty rates.

The Great Depression highlighted the need for more detailed economic data.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). 28 Terzi, A. Economic Policy-Making Beyond GDP: An Introduction. European Economy Discussion Paper 142. (2021). In the early 1930s, United States Department of Commerce Commissioned Simon Kuznets developed a set of national accounts which were the prototype of the GDP accounts. During World War II and in the post-war era, GDP accounting developed to assist with planning militarization costs. Countries began to compare GDP per capita internationally to assess economic success and the relative social progress of nations, known as the growth model of progress. “Economic growth is defined as an increase in GDP, that is, an increase in the monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country in a given time period.”12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022). , p.6 Even though it is since then seen as a valuable comparative indicator and benchmark, there are limits and critiques especially regarding its eligibility for measuring the welfare of a nation and its global standardization which will be further examined in section 3.1.4.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the growth paradigm took off since economic growth became the primary economic policy for national governments as it was seen to be essential for decreasing poverty, increasing living standards and reaching stable levels of employment.12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022). Growth therefore became the stabilization mechanism for capitalist societies addressing post-war issues.Since then, the dominant economic growth paradigm is closely linked to neoclassical economics.29 Brand-Correa, L. et. al. Economics for people and planet – moving beyond the neoclassical paradigm. Lancet Planet Health 6, 371-379 (2022). This approach focuses on the pareto efficient allocation of scarce resources. Pareto efficiency means that “nobody can be made better off without others being made worse off”29 Brand-Correa, L. et. al. Economics for people and planet – moving beyond the neoclassical paradigm. Lancet Planet Health 6, 371-379 (2022). , p.371. Economic growth and especially growth in GDP is seen as a driver for the improvement of living standards and life expectancy of all rather than a redistribution tool for the poor.29 Brand-Correa, L. et. al. Economics for people and planet – moving beyond the neoclassical paradigm. Lancet Planet Health 6, 371-379 (2022). According to Alexander (2014) “growth in GDP provides governments, by way of taxation, with more resources to pay for the nation’s most important social services.”22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). , p.2. It therefore contributes directly to social, economic and ecological wellbeing as it offers national security and environmental protection programs for example.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). Growth leads to growing personal incomes and as a result, to more freedom to purchase things people want or need.On the one hand, Alexander (2014) states that there is an optimal scale at the microeconomic level. If growth costs more that it is worth this is considered uneconomic growth. Hiring more employees or buying more industrial plants will not maximize profit. On the other hand, he points out that there is no optimal scale at macroeconomic level for the growth paradigm since there are no biophysical limits to growth. Technological and allocative efficiency innovations allow the economy to expand infinitely even though raw materials are finite.

3.1.2 Emergence of Growth Critique

According to Döring (2019) 30 Döring, T. Alternativen zum umweltschädlichen Wachstum. Wirtschaftsdienst 99 (7), 497-504 (2019). critique on economic growth has been existent as long as economic growth itself. There are multiple economists who have published growth critique over the time and three, who have shaped the discourse and continue to do so today will be presented in the following.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). In 1798, the ‘Essay on the Principle of Population’, also known as the Malthusian Catastrophe, was published by Thomas Malthus. He assumes that population growth will outpace the ability of agricultural production to feed people.31 Malthus, T. An Essay on the Principle of Population. (J. Johnson, 1798). Malthus was the first to lift up the idea that unlimited growth, especially population growth, coupled with economic growth would lead to social and environmental limits sooner or later. 22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). The first defence of a postgrowth economy was published in 1848 as the ‘Principles of Political Economy’ by John Stuart Mill.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). Mill raises the question of the purpose of society’s industrial progress, challenging the idea that economic growth is inherently valuable.32 Mill, J. S. Principles of Political Economy. (John W. Parker, 1848). He suggests that economic growth might become purposeless, prompting consideration of how much growth is necessary and why. Mill proposes a ‘stationary state’ where society maintains stability in population and physical capital, focusing on technological improvement and the ‘Art of Living’. In this state, technology would reduce labour rather than accumulate wealth, aligning with modern efforts to enhance quality of life and reduce ecological impact. He also believes that a focus on cultural, moral, and social progress, rather than material gain, would flourish in such a state of mind. Later, Herman Daly (1974)33 Daly, H. E. The Economics of the Steady State. The American Economic Review 64. (2), 15-21 (1974). based his concept of a ‘steady state economy’ on this stationary state description. He describes an optimal sustainable state as an economy that neither grows nor shrinks physically but keeps material throughput within the biophysical limits and is still able to yield qualitative change and innovation. In 1972, the Club of Rome published the report ‘Limits to Growth’ which reached broad attention internationally and became the most popular growth critique according to literature.15 Evroux, C., Spinaci, S. & Widuto, A. From growth to beyond growth: Concepts and challenges. European Parliamentary Research Service. (2023). 30 Döring, T. Alternativen zum umweltschädlichen Wachstum. Wirtschaftsdienst 99 (7), 497-504 (2019). 34 Jackson, T. The Post-growth Challenge: Secular Stagnation, Inequality and the Limits to Growth. Ecological Economics 156 (12), 236-246 (2018). The Club of Rome is an informal international organization 35 Meadows, D. H. et. al. The Limits to Growth-A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. (Universe Books, 1972). with the purpose to “foster understanding of the varied but interdependent components-economic, political, natural, and social-that make up the global system in which we all live; to bring that new understanding to the attention of policy-makers and the public worldwide.”35 Meadows, D. H. et. al. The Limits to Growth-A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. (Universe Books, 1972). , p.9. The report states that “[t]he basic behaviour mode of the world system is exponential growth of population and capital, followed by collapse”35 Meadows, D. H. et. al. The Limits to Growth-A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. (Universe Books, 1972). p.142. The main statement therefore is that exponential increase in economic output cannot be sustained in the long-term since the planet’s resources and absorptive capacities are finite.35 Meadows, D. H. et. al. The Limits to Growth-A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. (Universe Books, 1972). Pollution and resource depletion would lead to reaching earthly limits and a collapse as food production declines.

3.1.3 Ecological and Social Limits to Growth

In the last decades, growth criticizing literature has been particularly dealing with ecological and social limits to growth. 11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). 12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022).

According to Büchs and Koch (2017)11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). economic growth is linked to an exponentially rising use of non-renewable resources and the generation of waste which threatens the functioning of ecosystems and leads as stated before to limits of seven out of eight planetary boundaries. 1 Rockström, J. et al. Safe and just Earth system boundaries. Nature 619, 102-111 (2023). The 6th Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2023)36 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Climate Change 2023. Synthesis Report. Summary for Policy Makers. (2023). reports that the global surface temperature has risen 1.1 Degree Celsius since 1850 to 1900 in 2011 to 2020. Local temperature increases can even be higher than that. NASA (2023) 37 NASA. Carbon dioxide. Climate NASA https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/carbon-dioxide/ (2023) has reported the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere at 421 parts per million (ppm) in May 2023. The concentration has therefore risen over 100 ppm over the past 60 years. Human activities contributed to 50 per cent of this increase since the beginning of the industrialization. The current concentration is seen as not safe anymore since a level of 350 ppm is considered as the long-term limit of CO2. The growth paradigm is based on the idea that technological and allocative efficiency innovations allow the economy to expand infinitely even though raw materials are finite leading to the decoupling of growth from environmental impact.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). However, current evidence does not show that decoupling is taking place so far. 38 Vadén, T. et. al. Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorization and review of research literature. Environmental Science and Policy 112, 236-244 (2020). 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). According to Vadén et al. (2020) 38 Vadén, T. et. al. Decoupling for ecological sustainability: A categorization and review of research literature. Environmental Science and Policy 112, 236-244 (2020). who conducted a survey on recent research on decoupling including 179 articles from 1990 to 2019, there is no evidence of economy-wide, national nor international resource decoupling and that there is evidence of recoupling through raising material intensity.

Regarding the social limits, Büchs and Koch (2017) 11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). consider the benefits of economic growth as unequally distributed and state that they have not reached the people in need as predicted. Poverty and income inequality remain high and are even increasing in a couple of countries. Social pressure, driven by advertisement for example, to keep up with living-standards and consumer habits can lead to stress and even mental disorders. Technological innovation is increasing job insecurity and the fear for job losses. Indigenous communities in developing countries reliant on local natural resources often suffer exploitation, pollution or even destruction through the inclusion of local economies into global value chains. The Happiness Income Paradox (HIP), or Easterlin Paradox, is according to its publisher an explanatory phenomenon for the limits of social comparison in the long-term and internationally.40 Easterlin, R. A. & O’Connor, K. J. The Easterlin Paradox. IZA Discussion Papers No. 13923 (2020). It is believed that happiness is connected to wealth and income and that happiness varies directly with income, but over time, happiness does not increase when a country’s income increases in the long-term since relative income matters more than absolute income.

Overall, according to Büchs and Koch (2017) “ecological and social implications of growth cannot be separated from each other as ecological destruction is inevitably going to undermine people’s wellbeing in the long term.“11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). , p.52 An example can be climate change forcing people to migrate.11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

3.1.4 Critique of GDP

Even though Simon Kuznet developed the prototype for the GDP, he “argued against making this fundamental change in perspective permanent, and he urged governments to return to focusing on income and its distribution”28 Terzi, A. Economic Policy-Making Beyond GDP: An Introduction. European Economy Discussion Paper 142. (2021). , p.7, but was ignored.28 Terzi, A. Economic Policy-Making Beyond GDP: An Introduction. European Economy Discussion Paper 142. (2021). It is the increasing ecological and social limits that have brought up the discussion again whether the GDP as the primary indicator is sufficient for measuring growth, wealth and quality of life in general.11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). 28 Terzi, A. Economic Policy-Making Beyond GDP: An Introduction. European Economy Discussion Paper 142. (2021). 41 Palumbo, A. A post-GDP critique of the Europe 2020 strategy. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 72, 47-63 (2013). The major critique of the GDP is that it excludes the environmental and social costs generated by production. Since emitting greenhouse gases is not associated with costs, damages are not reflected in the indicator. From an ecological perspective, the GDP might even increase as a consequence of environmental damages for example if deforestation increases. From an individual and social wellbeing point of view, the GDP is also seen as inadequate tool as it only focuses on the material aspects of wellbeing. The measurement includes all market transactions whether they increase or decrease welfare such as expenditures that arise from divorces for example. It excludes the informal economy in households, volunteering work, free government services, roles of capital stocks as well as leisure which can all be important contributions for the wellbeing. Furthermore, the GDP is not informative on the distribution of benefits and incomes in a society.“[A] rise of GDP can be consistent with a rise of inequality of income and wealth.”11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). , p.46 In addition, the indicator cannot be compared among different countries with different sizes of the informal economy in terms of quality of life.11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017).

Most critics argue that the GDP should still not be abolished as a whole.28 Terzi, A. Economic Policy-Making Beyond GDP: An Introduction. European Economy Discussion Paper 142. (2021). 42 Kroker, R. Wachstum, Wohlstand, Lebensqualität: Brauchen wir einen neuen Wohlstandsindikator? ifo Schnelldienst 64 (4), 3-6 (2011) Rather, the focus should lay on closing gaps, increasing its expressiveness and making it more comparable internationally by having uniform standards. In addition, alternative indicators could be included which will be further examined in section 3.2.5.

3.2 Towards a Post- and Degrowth Future

3.2.1 Economic Frameworks

The emerging body of post- and degrowth literature provides a breadth and diversity of ideas for many sectors and areas that would be affected in a future that departs from traditional growth-driven models. Moreover, postgrowth futures will most likely “be highly geographically and temporally heterogenous”43 Crownshaw, T. et al. Over the horizon: Exploring the conditions of a post-growth world. The Anthropocene Review 6 (1), 117-141 (2019). , p.123 due to the different starting points of different states, especially between the global North and South. To give an overview of the multifaceted scientific landscape, this section will focus on key economic, political, social, and technological frameworks and concepts central to this discourse.

Concerning the economy in a post- or degrowth context, most scholars build on the foundations of growth critique that have been elaborated in the previous section. Economic concepts that have received great attention in the scientific community in the last decades include the works of Jackson (2017)4 Jackson, T. Prosperity without growth. Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Second Edition. (Routledge, 2017). , Paech (2009, 2018) 44 Paech, N. Grundzüge einer Postwachstumsökonomie. Postwachstumsökonomie. http://www.postwachstumsoekonomie.de/material/grundzuege/ (2009) 7 Paech, N. Befreiung vom Überfluss. Auf dem Weg in die Postwachstumsökonomie. 10. Auflage. (Oekom Verlag, 2018). and Latouche (2009)26 Latouche S. Farewell to Growth. (Polity Press, 2009). which provide the most holistic frameworks of a post- or degrowth economy.

Jackson (2017)4 Jackson, T. Prosperity without growth. Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Second Edition. (Routledge, 2017). paints the picture of a ‘Cinderella economy’ that remains within ecological limits highlighting the potential of de-materialized services, reduced working hours and high levels of work satisfaction and participation in the life of society. The necessary transition shall be realized by ecological investments and a structural change that enhances citizens’ capabilities to flourish in less materialistic ways.

Paech’s (2009) 44 Paech, N. Grundzüge einer Postwachstumsökonomie. Postwachstumsökonomie. http://www.postwachstumsoekonomie.de/material/grundzuege/ (2009) postgrowth vision builds upon the concept of sufficiency and constitutes of five central developmental steps. These include decluttering and deceleration processes to eliminate unnecessary time, money and resource consuming activities, a balance between self-sufficiency and external supply as well as a regionalization of economic structures. Moreover, remaining consumption demands shall be realized under the concept of ‘material zero-sum games’ by extending the use of products and creating value without the need for extra material production whereas institutional innovations shall support consumers and firms to follow these paths.

As a degrowth advocate, Latouche (2009) envisions an economy “in which we can live better lives whilst working less and consuming less”26 Latouche S. Farewell to Growth. (Polity Press, 2009). , p.9 He proposes a circle of eight ‘R’s that represent the stages of the transformation to a degrowth economy. While values shall be re-evaluated and concepts of wealth reconceptualized, the production system of the economy needs to be restructured according to these changes. This does not only include redistributing wealth but also relocalizing production. Moreover, negative impacts of consumption and production need to be reduced, possibly by shortening the working week and decreasing overconsumption and waste. This can also be supported by reusing and recycling activities.

In conclusion, central economic aspects discussed in post- and degrowth literature are minimizing the negative environmental impacts of production and consumption by enacting structural shifts to labor-intensive and low-productivity sectors, such as the service sector, and localizing economic structures. Moreover, a re-organization of work and labor and more equal distribution of income and wealth are seen as crucial.

3.2.2 Political Frameworks

In the heterogenous literature on post- and degrowth futures and their political implications, the question of the role of the state and models of democracy is of central importance. While some scholars believe that it is possible to achieve the necessary transition towards an economy and society that does not exceed environmental limits and ensures social wellbeing through today’s centralized democratic state and its institutions, others call for a more radical overhaul of the political-economic system. 16 Alexander, S. & Rutherford, J. The Deep Green Alternative. Debating Strategies of Transition. Simplicity Institute Report 14a. (2014). 45 Cattaneo, C., D’Alisa, G., Kallis, G. & Zografos, C. Degrowth futures and democracy. Futures 44 (6), 515-523 (2012).

In growth criticizing literature, Illich’s (1973) 46 Illich, I. Energy and Equity. (Harper & Row, 1973). conception on the relationship between scale and democracy presents a first key influence in this context. His main argument is that above a certain scale of a system, the distribution of power becomes unequal because the complexity can only be managed by experts of a ruling class. This implies that “only small systems can be democratically and collectively controlled”45 Cattaneo, C., D’Alisa, G., Kallis, G. & Zografos, C. Degrowth futures and democracy. Futures 44 (6), 515-523 (2012). , p. 516. Therefore, scholars point not only to the importance of a participation but also to the role of local level political decision-making to allow for more autonomy.26 Latouche S. Farewell to Growth. (Polity Press, 2009). 47 Weiss, M. & Cattaneo, C. Degrowth – Taking Stock and Reviewung an Emerging Academic Paradigm. Ecological Economics 137, 220-230 (2017). 48 Bonaiuti, M. Growth and democracy: Trade-offs and paradoxes Futures 44 (6), 524-534 (2012).

Ott (2012)49Ott, K. Variants of de-growth and deliberative democracy: a Habermasian proposal. Futures 44 (6), 571-581 (2012) argues that a Habermasian deliberative liberal democracy would be most compatible with a postgrowth scenario as it subordinates the economy to ethical principles and politically agreed conditions. This democratic model is furthermore characterized by a deepened dialogue between state, civil society and private actors. Others advocate for a more radical transformation, where economic democracy presents a central aspect.17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). 45 Cattaneo, C., D’Alisa, G., Kallis, G. & Zografos, C. Degrowth futures and democracy. Futures 44 (6), 515-523 (2012). Economic democracy can be defined as “a system of checks and balances on economic power and support for the right of citizens to actively participate in the economy regardless of social status, race, gender, etc.”.50 Johanisova, N. & Wolf, S. Economic democracy: A path for the future? Futures 44, 562-570 (2012). , p.564 It shall ensure more participation in decision-making within companies and a mitigation of the growth pressure in profit-oriented enterprises. Especially within the degrowth movement, the idea of real and direct democracy is promoted.17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). The idea can be traced back to Castoriadis (1987)51 Castoriadis, C. The Imaginary Institution of Society. (The MIT Press, 1987). which highlights the ability of direct democracy to allow for autonomous self-institution. Most post- and degrowth advocates see a crucial role for state action, in contrast to some eco-anarchists believing that real change could only emerge from below.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014).

However, under current conditions, a development towards these ideas of a postgrowth democracy seems highly unlikely due to the absence of movement toward a political transition of that order.17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). Instead, some scholars warn that without social forces that support this kind of political change, it is more likely that in a decreasing or stagnating economy there would be a shift towards a more authoritarian direction.17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). 43 Crownshaw, T. et al. Over the horizon: Exploring the conditions of a post-growth world. The Anthropocene Review 6 (1), 117-141 (2019). This highlights the crucial role of “strengthening social movements and political tendencies aiming to revitalize democracy and politicize economics”17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). , p. 4.18.

To achieve the necessary economic and social changes towards post- and degrowth scenarios, scholars have compiled several policy proposals and instruments that can support this transition. The following table provides a non-exhaustive overview of the recommendations often mentioned in post- and degrowth literature to achieve the overarching economic goals elaborated in the previous section.

| Policy Objective | Policy Instrument | Sources |

| Policies to lower production/consumption | Reduction of working hours Job guarantees/work sharing | 4 Jackson, T. Prosperity without growth. Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Second Edition. (Routledge, 2017). 52 Victor, P. Managing Without Growth: Slower By Design, Not Disaster. (Edward Elgar Publishing, 2008). 53 Videira, N., Schneider, F., Sekulova F. & Kallis, G. Improving understanding on degrowth pathways: an exploratory study using collaborative causal models. Futures 55, 58-77 (2014). 5 Kallis, G., Kerschner, C. & Martinez-Alier, J. The economics of degrowth. Ecological Economics 84, 172-180 (2012). 54 Alcott, B. Impact caps: why population, affluence and technology strategies should be abandoned. Journal of Cleaner Production 18 (6), 552-560 (2010). |

| Policies to reduce inequality | Basic income; minimum/maximum income | 11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). 18 Schneider, F., Kallis, G. & Martinez-Alier, J. Crisis or opportunity? Economic degrowth for social equity and ecological sustainability. Introduction to this special issue. Journal of Cleaner Production 18. (1), 511-518 (2010). 55 Ferguson, P. Post-growth Politics. A Critical Theoretical and Policy Framework for Decarbonisation. (Springer International Publishing, 2018) 56 Alexander, S. Property beyond Growth. Toward a Politics of Voluntary Simplicity. University of Melbourne. (2011). |

| Macroeconomic policies for above objectives | Environmental taxes and caps Progressive taxation Disinvestment from dirty sectors and investment in green sectors New modes of ownership Economic legislation favoring socially and ecologically responsible firms | 4 Jackson, T. Prosperity without growth. Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Second Edition. (Routledge, 2017). 55 Ferguson, P. Post-growth Politics. A Critical Theoretical and Policy Framework for Decarbonisation. (Springer International Publishing, 2018) 57 Daly, H. & Farley, J. Ecological Economics. Principles and Applications. 3rd edition. (Island Press, 2011). 11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). 7 Paech, N. Befreiung vom Überfluss. Auf dem Weg in die Postwachstumsökonomie. 10. Auflage. (Oekom Verlag, 2018). 20 Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics 70 (5), 873-880 (2011). 43 Crownshaw, T. et al. Over the horizon: Exploring the conditions of a post-growth world. The Anthropocene Review 6 (1), 117-141 (2019). 58 Sekulova, F., Kallis, G., Rodriguez-Labajos, B. & Schneider, F. Degrowth: from theory to practice. Journal of Cleaner Production 38, 1-6 (2013). 59 Gebauer, J., Lange, S. & Posse, D. Wirtschaftspolitik für Postwachstum auf Unternehmensebene. Drei Ansätze zur Gestaltung. In Postwachstumspolitiken: Wege zur wachstumsunabhängigen Gesellschaft (eds. Adler, F. & Schachtschneider, U.) 239-252. Oekom Verlag, 2017) |

Table 1: Policy Instruments for Post- and Degrowth Scenarios

Own Illustration

3.2.3 Technological Frameworks

In current economic thinking, technological change and innovation are closely coupled with economic growth. This assumption can be traced back to Schumpeter (1934) 60 Schumpeter, J. The Theory of Economic Development: an Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. (Harvard University Press, 1934) who has coined the idea of creative destruction and demonstrates that technological change is the driver of capitalist expansion. Pansera and Fressoli (2021)9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization, 28 (3), 380-404 (2021). summarize current perspectives towards technological progress under the terms of technological determinism and technological productivism. Technological determinism describes the belief that technological progress “is inevitable and the innovation pace in a given economy is bound to increase indefinitely”9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization, 28 (3), 380-404 (2021). , p.383 whereas technological productivism suggests that innovation always leads to new jobs, economic growth as well as prosperity and is thus a good per se. As assumed in green growth strategies, innovation is also considered to be able to expand limits to growth imposed by resource scarcity and help to solve societal problems. 61 Pollex, J. & Lenschow, A. Surrendering to growth? The European Union’s goals for research and technology in the Horizon 2020 framework. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1863-1871 (2018).

Post- and degrowth scholars however point out to several limitations that can be associated with technological innovation. Some of the earliest growth critics have shown skepticism towards technologies within a post- or degrowth context.62 Ellul, J. The Technological Society. (Vintage Books, 1964). 63 Illich, I. Tools for Conviviality. (Harper & Row, 1973). 64 Mumford, L. Myth of the Machine. Technics and Human Development. (Mariner Books, 1967). Ellul (1964) 62 Ellul, J. The Technological Society. (Vintage Books, 1964). argues that the technological system has become uncontrolled and independent of human needs and thus technological change is only pursued for technological change’s sake. Similarly, Illich (1973) 63 Illich, I. Tools for Conviviality. (Harper & Row, 1973). indicates that unguided technical change can result in an overgrowth of tools that cannot be aligned with a sustainable society and thus highlights the need for convivial tools that re-establish the autonomy of humans. These critical views on technology are still shared by some scholars.9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization, 28 (3), 380-404 (2021). 26 Latouche S. Farewell to Growth. (Polity Press, 2009). 22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). Mostly, it is pointed out that current evidence suggests that due to rebound effects, technological fixes will most likely not provide an escape from biophysical limits to growth.65 Wiedmann, T. et al. The material footprint of nations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112 (20), 6271-6276 (2013). 66 Polimeni, J., Mayumi, K., Giampietro, M. & Alcott, B. The Myth of Resource Efficiency: The Jevons Paradox. (Earthscan from Routlede, 2009). Instead, in an economy beyond growth with lower energy and resource requirements, it might be expected that technological sophistication and automation decrease. 43 Crownshaw, T. et al. Over the horizon: Exploring the conditions of a post-growth world. The Anthropocene Review 6 (1), 117-141 (2019).

However, literature also provides several approaches that try to align innovation and the notions of a post- or degrowth economy. 67 Likavcan, L. & Scholz-Wäckerleb, M. Technology appropriation in a de-growing economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1666-1675 (2018). 68 Grunwald, A. Diverging pathways to overcoming the environmental crisis: A critique of eco-modernism from a technology assessment perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1854-1862 (2018). 69 Vetter, A. The Matrix of Convivial Technology – Assessing technologies for degrowth. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1778-1786 (2018) 70 Lizarralde, I. & Tyl, B. A framework for the integration of the conviviality concept in the design process. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1766-1777 (2018). Whereas scholars such as Heikkurinen (2018) 71 Heikkurinen, P. Degrowth by means of technology? A treatise for an ethos of releasement. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1654-1665 (2018). come to the conclusion that refraining from technological practice is needed to obtain a degrowth society, others develop frameworks to evaluate technology and adapt or design them according to certain criteria. 72 Kerschner, C., Wächter, P., Nierling, L. & Ehlers, M. Degrowth and Technology. Towards feasible, viable, appropriate and convivial imaginaries. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1619-1636 (2018). On the basis of Illich’s63 Illich, I. Tools for Conviviality. (Harper & Row, 1973). work, Vetter (2018) 69 Vetter, A. The Matrix of Convivial Technology – Assessing technologies for degrowth. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1778-1786 (2018) has developed a ‘Matrix of Convivial Technology’, that sums up basic values and criteria into the five dimensions of relatedness, accessibility, adaptability, bio-interaction and appropriateness. Comparably, Lizarralde and Tyl (2018) 70 Lizarralde, I. & Tyl, B. A framework for the integration of the conviviality concept in the design process. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1766-1777 (2018). propose two guidelines and recommendations that foster the design for conviviality.

Post- and degrowth literature also studies concrete measures and tools that might offer examples on how to align technology with the ideas of post- and degrowth, Kallis et al. (2018) 17 Kallis, G. et al. Research on Degrowth. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 43, 4.1-4.26 (2018). , Kerschner et al. (2018) 72 Kerschner, C., Wächter, P., Nierling, L. & Ehlers, M. Degrowth and Technology. Towards feasible, viable, appropriate and convivial imaginaries. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1619-1636 (2018). as well as Pansera and Fressoli (2021) 9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization, 28 (3), 380-404 (2021). provide an overview of respective projects. These include amongst many others low-tech technologies (e.g. solar shower bags) that are compatible with low energy scenarios, so-called Bike Kitchens that provide space for repairing or building one’s own bike as well as diverse grassroot initiatives such as ‘Design Global Manufacture Local’ processes which put emphasis on developing and sharing designs through global digital commons and implementing them on a local level and thus helping people to become more autonomous. 73 Alexander, S. & Yacoumis, P. Degrowth, energy descent, and ‘low-tech’ living: Potential pathways for increased resilience in times of crisis. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1840-1848 (2018). 74 Bradley, K. Bike Kitchens – spaces for convivial tools. Journal of Cleaner Production 197 (2), 1676-1683 (2018). 75 Kostakis, V., Niaros, V., Dafermos, G. & Bauwens, M. Design global, manufacture local: exploring the contours of an emerging productive model. Futures 73, 126-135 (2015).

3.2.4 Social Frameworks

When moving beyond the current paradigm of continuous economic growth, post- and degrowth literature argues that there will also be the need for cultural and behavioural changes within the society. 20 Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics 70 (5), 873-880 (2011). Currently, it may seem unlikely that citizens show great support of post- or degrowth scenarios due to concerns about potential negative wellbeing implications. 76 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing. Futures 105, 155-165 (2019). Especially in a degrowth context, income and material levels of some individuals will most likely be affected, which might be perceived as a welfare loss. 20 Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics 70 (5), 873-880 (2011). This is due to the fact that the growth paradigm is not only entrenched in economic thinking, but also in individual people’s minds and identities. 76 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing. Futures 105, 155-165 (2019).

However, post- and degrowth ideas build on the vision that economic activity should mainly be pursued to maintain or improve long-term human well-being and that this is also possible in the absence of growth.11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). Therefore, it is argued that a fundamental re-ordering of values is necessary to ensure that a fulfilling life does not solely depend on income, consumption and economic growth.77 Nørgård, J. Happy degrowth through more amateur economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 38, 61-70 (2013). 78 Fournier, V. Escaping from the economy: the politics of degrowth. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 28 (11), 528-545 (2008). Postgrowth literature suggests different conceptions of well-being, such as Elgin’s (1982)79 Elgin, D. Voluntary Simplicity: An Ecological Lifestyle that Promotes Personal and Social renewal. (Bantam Books, 1982). ‘voluntary simplicity’, Soper’s (2008)80 Soper, K. Alternative Hedonism, Cultural Theory and the Role of Aesthetic Revisioning. Cultural Studies 22 (5), 567-587 (2008). ‘alternative hedonism or Muraca’s (2012)81 Muraca, B. Towards a Fair Degrowth-Society: Justice and the Right to a “Good Life” Beyond Growth Futures 44 (6), 535-545 (2012). ‘good life’. Comparably, Jackson (2017) 4 Jackson, T. Prosperity without growth. Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. Second Edition. (Routledge, 2017). and Cassiers (2015)82 Cassiers, I. Redefining Prosperity. (Routledge, 2015) provide alternative notions of prosperity. They all share the idea that a prosperous life is rooted in, amongst other things, finding meaning and purpose in life, having the opportunity to develop into one’s desired self and nurturing relationships.11 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Postgrowth and Wellbeing. Challenges to Sustainable Welfare. (Springer International Publishing, 2017). In this context, scholars point out to the importance of citizens’ participation in political decision-making, educational activities and refraining from only relying on top-down interventions. 43 Crownshaw, T. et al. Over the horizon: Exploring the conditions of a post-growth world. The Anthropocene Review 6 (1), 117-141 (2019). 76 Büchs, M. & Koch, M. Challenges for the degrowth transition: The debate about wellbeing. Futures 105, 155-165 (2019). 83 Smith, T., Baranowski, M. & Schmid, B. Intentional degrowth and its unintended consequences: Uneven journeys towards post-growth transformations. Ecological Economics 190, 1-8 (2021).

3.2.5 Alternative Indicators

The aforementioned limitations of the use of GDP as a sole indicator for welfare are widely acknowledged, not only in the post- and degrowth literature. 84 Strunz, S. & Schindler, H. Identifying barriers towards a post-growth economy. UFZ Discussion Papers. Department of Economics. (2017). In the past years, various indicators that account for environmental and social aspects not reflected by GDP have been developed and may present an alternative measure of well-being.

Costanza et al. (2014) 85 Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Giovannini, E., Lovins, H., McGlade J. & Pickett, K. Time to leave GDP behind. Nature 505, 283-285 (2014). provide three broad categories into which alternative indicators can be divided into: adjusted economic measures, subjective measures of well-being and weighted composite indicators. This classification is congruent with O’Neill’s (2012) 19 O’Neill, D. Measuring progress in the degrowth transition to a steady state economy. Ecological Economics 84, 221-231 (2012). classification, with the exception that the latter views individual biophysical and social indicators as an additional category. A non-exhaustive list of examples for each category can be derived from the table.

| Adjusted Economic Measures | Subjective Measures of Well-Being | Weighted Composite Indicators | Biophysical and Social Indicators |

| – Genuine Progress Indicator – Sustainable Economic Welfare – Cost-Benefit Policy Analysis | – World Values Survey – Gross National Happiness | – Happy Planet Index – Better Life Index – Human Development Index – Social Progress Index – O’Neill (2012)19 O’Neill, D. Measuring progress in the degrowth transition to a steady state economy. Ecological Economics 84, 221-231 (2012). | Biophysical: – Material Flow Accounting, Ecological Footprint, CO2 emissions, etc. Social: – Inequality, leisure time, unemployment rate, poverty levels, etc. |

Table 2: Categories and Examples of Alternative Indicators to GDP

Own Illustration

Adjusted economic measures are expressed in monetary terms and expand economic key figures so that they reflect social and environmental factors. 85 Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Giovannini, E., Lovins, H., McGlade J. & Pickett, K. Time to leave GDP behind. Nature 505, 283-285 (2014). The Genuine Progress Indicator for example considers personal consumption expenditures and incorporates over twenty adjustments to account for factors such as crime, volunteer labor, pollution and climate change. 86 Berik, G. Measuring what matters and guiding policy: An evaluation of the Genuine Progress Indicator. In: International Labour Review 159 (1), 71-94 (2020). Subjective measures of well-being can be derived from surveys such as the Gross National Happiness index used in Bhutan to measure the happiness and wellbeing of the Bhutanese population within nine domains. 87 Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Index. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative https://ophi.org.uk/policy/bhutan-gnh-index/ (2023). Weighted composite measures combine several subjective and objective indicators and compress a complex set of data into a single indicator. 85 Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Giovannini, E., Lovins, H., McGlade J. & Pickett, K. Time to leave GDP behind. Nature 505, 283-285 (2014). 19 O’Neill, D. Measuring progress in the degrowth transition to a steady state economy. Ecological Economics 84, 221-231 (2012). An example is the Happy Planet Index which multiplies data on life expectancy and experienced wellbeing and divides it by a measure of ecological footprint. 88 Happy Planet Index. Happy Planet Index 2021. Methodology Paper. https://happyplanetindex.org/wp-content/themes/hpi/public/downloads/happy-planet-index-methodology-paper.pdf (2021). O’Neill (2012)19 O’Neill, D. Measuring progress in the degrowth transition to a steady state economy. Ecological Economics 84, 221-231 (2012). also developed an indicator-system to capture degrowth and steady state economy indicators. Moreover, the author as well as Kallis (2011) 20 Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics 70 (5), 873-880 (2011). mention that it might also make sense to have a look at several individual indicators such as CO2 emissions or poverty levels that may indicate progress in the direction of post- or degrowth.

Despite the existence of well-developed alternative indicators of welfare, GDP currently remains an entrenched measure of economic progress. 84 Strunz, S. & Schindler, H. Identifying barriers towards a post-growth economy. UFZ Discussion Papers. Department of Economics. (2017). This might be partly due to technical or data limitations and methodological drawbacks of the alternatives, but various scholars also point out to political barriers. 12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022). 84 Strunz, S. & Schindler, H. Identifying barriers towards a post-growth economy. UFZ Discussion Papers. Department of Economics. (2017). 85 Costanza, R., Kubiszewski, I., Giovannini, E., Lovins, H., McGlade J. & Pickett, K. Time to leave GDP behind. Nature 505, 283-285 (2014). Not only is there a lack ofconsensus on potential alternatives but also mostly insufficient possibility to influence them in the short term. Moreover, a shift from GDP is likely to worsen influence of some currently powerful interest groups. Other scholars point out that in general, post- and degrowth are concepts that, comparable to liberty, cannot be extensively expressed in numbers and that a focus on indicators might create a distraction from the fundamental and structural shift beyond growth.12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022). 20 Kallis, G. In defence of degrowth. Ecological Economics 70 (5), 873-880 (2011).

3.3 Weaknesses and Avenues for Future Research

3.3.1 Critique on Post- and Degrowth

The following critique will be divided into critique on postgrowth and critique on degrowth. For the transition from the growth paradigm towards a postgrowth economy, critics point out that the development lacks content as a concept and is too easily modelled and remodeled.22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). A framework is needed to reach enforceability and adapt to different organizational business structures. Furthermore, banking and financial system cannot simply change or adapt to a new economy without being rethought fundamentally. 22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). It is questionable what should be done with the debts in existence and loans that rely on the continuous money supply which would stop or decrease for example. Those debts will be harder or impossible to be repaid if growth changes.

Regarding degrowth, Alexander (2014)22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). argues that the term might be misinterpreted since it could be analyzed as something against progress and therefore negatively connoted. In addition, it is debatable whether the term is adequate especially since degrowth does not mean that all sectors are shrinking but that there are sectors such as the renewable energy sector where growth is accepted or needed.

According to Holemans (2023) “[p]rosperity without Growth […] is still difficult for many economists and opinion makers to conceive, as it contradicts the dominant thinking.” 89 Holemans, D. A Postgrowth Economy Needs New Institutions. In Imagining Europe Beyond Growth (eds. EEB, Think Tank Oikos, Green European Journal) 19-23 (2023). , p.19 Economic institutions need to change and rethink their goal of growth, competitiveness, short-term profits and meeting shareholder interests and rather turn to meeting people’s needs.89 Holemans, D. A Postgrowth Economy Needs New Institutions. In Imagining Europe Beyond Growth (eds. EEB, Think Tank Oikos, Green European Journal) 19-23 (2023). An overall cultural change is needed. This deep transformation of worldviews and structures and radical shift in values and norms is a strong contrast to business-as-usual approach which might make it difficult to motivate institutions to change since it might be seen as impossible. 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020).

3.3.2 Future Research

Likaj, Jacobs and Fricke (2022)12 Likaj, X. Jacobs, M., Fricke, T. Growth, Degrowth or Post-growth? Towards a synthetic understanding of the growth debate. Basic Papers. Forum for a New Economy 2. (2022). discuss in what areas growth might still be needed and point out that a clarification is necessary for future research. The progressive increase in efficiency in the use of renewable energy sources can be an example where economic growth is still seen as logical and rather a shift towards these less damaging sectors is needed.

Alexander (2014)22 Alexander, S. Post-Growth Economics: A Paradigm Shift in Progress. Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute. (2014). questions how or if it is possible to align a postgrowth economy with the property and market structures of capitalism. Moreover, he questions whether the term ‘degrowth’ is sufficient to express the transition that is needed or if alternatives are necessary.

Another question that remains is whether technological innovations will be able to decouple environmental impact from economic activity which is closely linked to techno-optimism.91 Alexander, S. & Rutherford, J. A critique of techno-Optimism: Efficiency without sufficiency is lost. In Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Governance (eds. Kalfagianni, A., Fuchs, D. & Hayden, A.) 231-241 (Routledge, 2019). According to Alexander and Rutherford (2019) in this sense “techno-optimism is the belief that the problems caused by economic growth can be solved by more economic growth (as measured by GDP), provided we learn how to produce and consume more efficiently through the application of science and technology”91 Alexander, S. & Rutherford, J. A critique of techno-Optimism: Efficiency without sufficiency is lost. In Routledge Handbook of Global Sustainability Governance (eds. Kalfagianni, A., Fuchs, D. & Hayden, A.) 231-241 (Routledge, 2019). , p.232

Maintaining social institutions like social security and health insurance in the face of declining economic output is seen as another challenge.92 Döring, T. & Aigner-Walder, B. The Limits to Growth – 50 Years Ago and Today. Intereconomics – Review of European Economic Policy 57 (3), 187-191 (2022). To address this challenge, the authors suggest several recommendations such as the transition to a public guaranteed standard pension to decrease reliance on economic growth or implementing supplementary funded provisions to support social security. However, further research is needed to develop specific measures.

4 Practical Implementation

4.1 Key Dimensions of Post- and Degrowth Business

4.1.1 Five Dimensions Framework

It is crucial to understand how the concept of a post- or respectively a degrowth economy is linked to the mechanisms of real societies, their agents and institutions.90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). Against the backdrop of the macroeconomic-centred literature and research on post- and degrowth, it is particularly important to operationalize these concepts for the microeconomic actors, i.e. businesses.93 Khamara, Y. & Kronenberg, J. Degrowth in business: An oxymoron or a viable business model for sustainability? Journal of Cleaner Production 177, 721-731 (2017). 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). Businesses and firms represent change agents that need to transform the existing structures of growth, productivism, consumerism and competition. In order to do so one needs to gain an understanding of which characteristics of existing business models can support such a transformation and are thus compatible with a post- and degrowth society. The research topic that interconnects the idea of an aggregated post- or degrowth economy and the practical implementation of this concept on the firm level is relatively young and so are the business models that are subject to this research. As of now, a clear-cut distinction between the business characteristics that can be aligned with postgrowth and the ones that are linked to degrowth concepts is not common. Therefore, most scientific papers use both, the degrowth and the postgrowth term interchangeably. 94 Froese, T., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hofmann, F. Degrowth-oriented organizational value creation: A systematic literature review of case studies. Ecological Economics 207, 1-84 (2023). This is also shown by the findings of Pansera and Fressoli (2021) 9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization. Special Issue: Theoretical Perspectives on Organizations and Organizing in a Post-Growth Era 28 (3), 380-404 (2021). , Gebauer (2018) 95 Gebauer, J. Towards Growth-Independent and Post-Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship in the SME Sector. Management Revue 29 (3), 230-256 (2018). as well as Nesterova (2020) 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). and Froese et. al (2023) 94 Froese, T., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hofmann, F. Degrowth-oriented organizational value creation: A systematic literature review of case studies. Ecological Economics 207, 1-84 (2023). on business characteristics that are respectively favorable for either a post- or degrowth transformation. The business attributes coincide in many ways, regardless of on which term the analysis was based on. In the following analysis both terms will subsequently be considered synonyms as well.

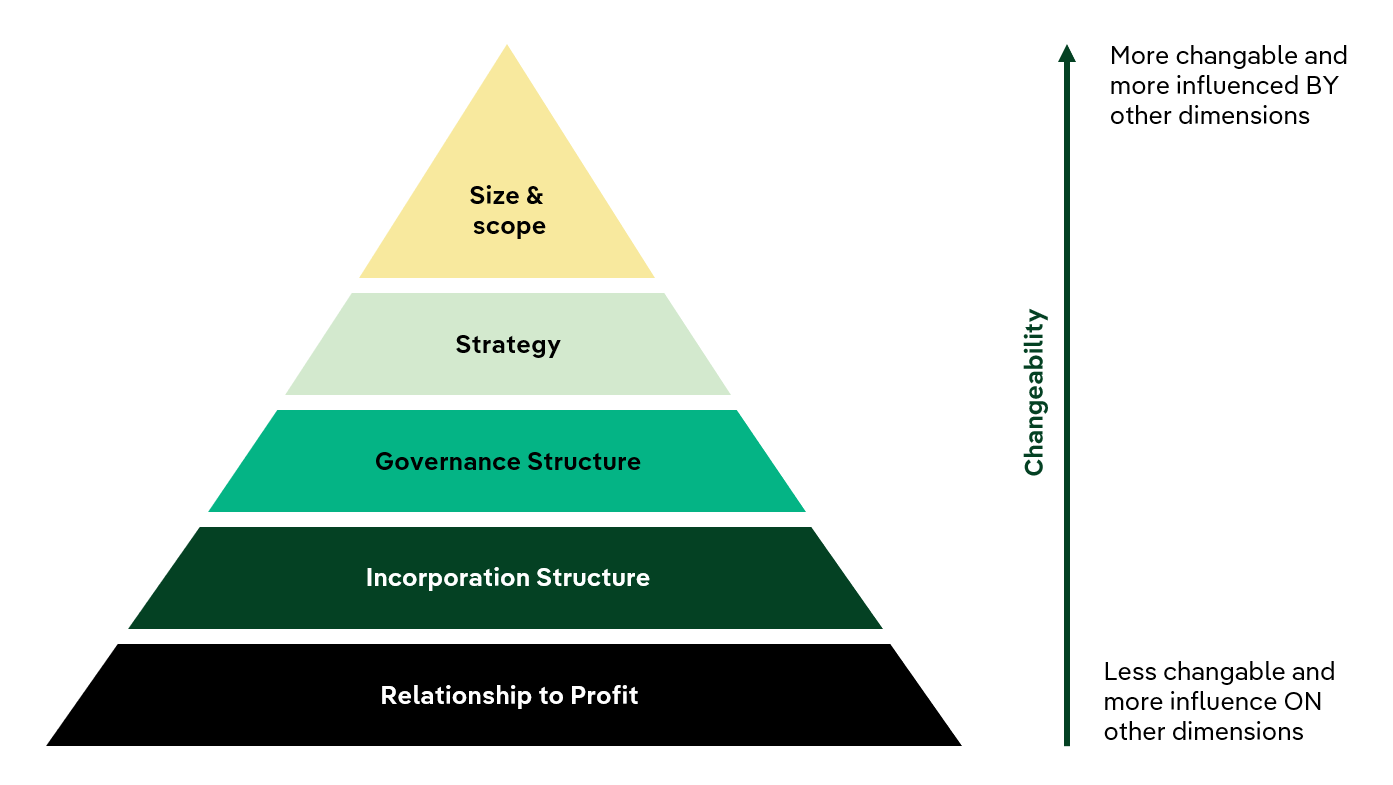

As mentioned, similar attributes and practices of businesses that are compatible with a post- and degrowth vision can be found in many scientific papers, they are however structured and categorized in different ways. 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). 93 Khamara, Y. & Kronenberg, J. Degrowth in business: An oxymoron or a viable business model for sustainability? Journal of Cleaner Production 177, 721-731 (2017). 94 Froese, T., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hofmann, F. Degrowth-oriented organizational value creation: A systematic literature review of case studies. Ecological Economics 207, 1-84 (2023). Hinton (2021) 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). structures his findings in five successive key dimensions: Relationship-to-profit, Incorporation structure, Governance structure, Strategy and Size and Scope. The dimensions represent institutional elements[1] of a business that can either be enabling or constraining factors for degrowth and postgrowth business.

Institutional elements towards the bottom of the figure are of a permanent and legally-binding nature, while dimensions at the top are less regulated and easily changeable. Legally-binding institutions have a high obligation to comply with and influence the elements towards the top. The dimensions above relate to purpose and goals, thus they can be altered to a certain degree, however, they are also constrained by the business’ legally-binding institutions. A firm can change its strategy in a short period of time without affecting its relationship-to-profit, if however, the firm decides to be no longer profit-oriented this will have a severe impact on the strategy. According to Hinton (2021) 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). , it is crucial to obtain an understanding of how the different dimensions relate to each other and how much effort it takes to change the structure of a certain dimension in order to effectively transform businesses. Hinton’s (2021)39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). approach offers the most holistic foundation for assessing to which degree a firm’s attributes correspond to post- and degrowth aspects since it allows for a complete picture. It includes all aspects of business, also the ones that are difficult to change from a legal point of view and considers how the different elements of business affect each other. It is therefore suitable to allocate the findings of other papers to Hinton’s (2021) 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). five key dimensions, if they are not yet included.

4.1.2 Size and Geographical Scope

This dimension “refers to how small versus large a business is, as well as how local vs. global it is”.39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). p.3 In the context of post- and degrowth literature, small and locally-rooted businesses without growth motives are frequently mentioned. 93 Khamara, Y. & Kronenberg, J. Degrowth in business: An oxymoron or a viable business model for sustainability? Journal of Cleaner Production 177, 721-731 (2017). These businesses avoid scaling up production, number of employees, or geographic extension by applying sufficiency-based limits to size of customers, production capacities, organizational complexity and avoid acquisitions. 95 Gebauer, J. Towards Growth-Independent and Post-Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship in the SME Sector. Management Revue 29 (3), 230-256 (2018). The IT consultancy BRM from Bremen for example does not intend to increase the level of sales, number of customers and number of employees, because at this ‘optimal firm size’ the quality of service and efficiency is the highest and growth could destroy the company’s success. 96 Liesen, A., Dietsche, C. & Gebauer, J. Successful Non-Growing Companies. Humanistic Management Network Research Paper No 25/15. (2015). Some firms even pursue production only to a subsistence-extent. This is in line with the idea of a right-size business that only satisfies real, basic human needs. 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). 97 Johanisova, N., Crabtree, T. & Franková, E. Social enterprises and non-market capitals: a path to degrowth? Journal of Cleaner Production 38, 7-16 (2013). Degrowth and postgrowth compatible businesses should be also embedded within the local communities they operate in. This is demonstrated by a localization and decentralization of sourcing, production and exchange as well as a generation of strong social networks and bonds. 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). 95 Gebauer, J. Towards Growth-Independent and Post-Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship in the SME Sector. Management Revue 29 (3), 230-256 (2018). A strong localization is also related to a reduced dependence on imported goods and a higher self-reliance that in turn minimizes the necessity for widespread and complex supply chains. In particular, small and medium sized firms demonstrate the attributes of post- and degrowth business with respect to size and geographical scope and are therefore frequently used as examples.95 Gebauer, J. Towards Growth-Independent and Post-Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship in the SME Sector. Management Revue 29 (3), 230-256 (2018). 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). The dimension is neither legally-binding nor does it relate to property rights of a company. The decision to grow and respectively to expand geographically is a normative one, that can relatively easy be changed if desired or if an alteration in other institutional elements of the business demand this.

4.1.3 Strategy

A business’ strategy comprises how the company uses its resources to achieve a certain purpose. In this context important elements are business management, -planning and -practices. 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). The strategy dimension encompasses a broad number of company attributes that are compatible with post- and degrowth business and has therefore been the main area of focus in the respective literature. The goals, norms and beliefs present in a business are directly linked to its strategy. In a post- and degrowth context, business models and goals are sufficiency oriented. Furthermore, instead of profit objectives, companies aim at satisfying real human needs as well as at enhancing the well-being of non-humans and nature. 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). 97 Johanisova, N., Crabtree, T. & Franková, E. Social enterprises and non-market capitals: a path to degrowth? Journal of Cleaner Production 38, 7-16 (2013). Values such as community, diversity, solidarity, equality, cooperation, responsibility as well as social justice are commonly found in those companies and are created in a collaborative and participative manner. 39 Hinton, J. Five key dimensions of post-growth business: Putting the pieces together. Futures 131, 1-14 (2021). 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). 9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization. Special Issue: Theoretical Perspectives on Organizations and Organizing in a Post-Growth Era 28 (3), 380-404 (2021). The relationship between post- and degrowth compatible companies and their employees, customers and suppliers and other stakeholders is generally of high quality, long-lasting and intimate. This is also supported by companies offering their employees an “appreciative and meaningful work environment”.95 Gebauer, J. Towards Growth-Independent and Post-Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship in the SME Sector. Management Revue 29 (3), 230-256 (2018). , p. 243 Employers that focus on developing human potential, increase spare time and respectively reduce work time are particularly suitable for a post- and degrowth transformation. Such a working environment, paired with a fair and needs-oriented salary then also ensures long-term employment and low turnover rates. 94 Froese, T., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hofmann, F. Degrowth-oriented organizational value creation: A systematic literature review of case studies. Ecological Economics 207, 1-84 (2023). 95 Gebauer, J. Towards Growth-Independent and Post-Growth-Oriented Entrepreneurship in the SME Sector. Management Revue 29 (3), 230-256 (2018).

Aside from focusing on encouraging their own workforce to act sustainably, post- and degrowth compatible businesses also pass on their values to their external environment. 90 Nesterova, I. Degrowth Business Framework: Implications for Sustainable Development. Journal of Cleaner Production 262, 1-10 (2020). Companies promote sustainability-oriented learning and engagement in the communities they operate in. 94 Froese, T., Lüdeke-Freund, F. & Hofmann, F. Degrowth-oriented organizational value creation: A systematic literature review of case studies. Ecological Economics 207, 1-84 (2023). This is also exhibited by businesses publicly sharing their intellectual property and knowledge e.g. in the form of free-licenses. 9 Pansera, M. & Fressoli, M. Innovation without growth: Frameworks for understanding technological change in a post-growth era. Organization. Special Issue: Theoretical Perspectives on Organizations and Organizing in a Post-Growth Era 28 (3), 380-404 (2021).