Author: Thomas Halsema, September 23, 2024

1 Introduction

“Social policy issues form the core of most domestic political debates and some of the major international ones too. Social policies speak directly to the major concerns of our everyday lives: they shape our working lives, school lives and home lives and influence our living standards and living conditions.”1, p.2

Social policy is constantly present in our everyday lives, often operating in ways that we are not aware of.1-3 It plays a foundational role in shaping the way we live.4 It is for these reasons, that scholars such as Beland (2010)5 argue, that “every citizen should know how it works, why it is there, and why they should care.”5, p.2

This is no easy task because social policy is a complex issue, Titmuss (1950)6 stated, that “there is no single or simple pattern of social policy but a variegated mosaic of services, detailed, dispersed and complex, all varying in character and importance”.6p.ix What is understood under social policy, can vary greatly.2,7 This is due to multiple reasons. For instance, there is no consensus regarding the definition of social policy.1,2,7-12 Furthermore, the term social policy has different meanings. It is referred to as an interdisciplinary field of study, as political output, or as a process to improving well-being.3,7,13,14

To gain a comprehensive understanding of social policy, it is essential to consider the role of the welfare state.11 The welfare state provides institutional context for social policy.15 This results in a fundamental intertwining of the two concepts.11 Although the two concepts are different and independent, they are frequently used interchangeably.11 As is the case with social policy, there is no universally accepted definition of the welfare state.16 In his discussion of the welfare state, Barr (2012)17 applies Titmuss’ (1950)6 assumption about social policy, whereby the concept can be understood as a mosaic. It therefore consist of varying definitions and perspectives.17.

In discussing the concept of the welfare state, it is crucial to recognise that the notion of a singular, unified welfare state is a misnomer.18 Rather, the reality is that a multitude of distinct types of welfare states coexist.18 Esping-Andersen (1990)19 addressed this phenomenon in his work, ‘Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism’, developing and empirically testing a typology that categorises welfare states into three distinct types. The use of the typology makes it possible to simplify complex issues, making it easier to analyse and compare them.20 Therefore, this work formed the foundation for the academic discourse on comparative welfare state analysis.20,21 Despite numerous discussions, further research and testing of the typology, it has retained its significance in the academic discourse to this day.20,21

The close relationship between the two concepts can also be attributed to their historical development. The historical development of social policy is dependent upon the underlying definition of the term.9 In the context of the present definition for this thesis, it can be argued that a form of social policy, as institutional measures, already existed in the Roman Empire, specifically in relation to the introduction of the ‘grain dole’, which was a measure to improve the well-being of the population with the provision of subsidised grain for the underprivileged and vulnerable.22 Nevertheless, there is a general consensus that social policy is a phenomenon of the modern era.9,23

The origins of modern social policy can be traced to the point at which the state begins to assume responsibility for the well-being of its citizens on a large scale.9 The historical development of social policy is often viewed from the perspective of its own national context.1 The majority of recent literature on social policy originates from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, with a particularly notable contribution from the United Kingdom.24 Therefore the potential points of origin for the historical development of social policy are often identified in the Poor Law in England in 1601, the accident insurance in France under Napoleon III, the veteran pensions in the USA, or the implementation of social insurance under Bismarck in Germany in the 1880s.9 The term ‘established welfare states’ is frequently used to describe these countries, whereas ’emerging welfare states’ is used to refer to those in the Global South and East. This thesis will examine the historical development of the former.25

An examination of the broader development of the welfare state reveals that it has consistently sought to address the perceived risks of its era.25 In the period following the publication of the Beveridge Report in 1942, a consensus emerged regarding the fundamental principles of the welfare state, leading to the implementation of five key measures.26 These five measures are commonly known as the ‘Big Five’ and are regarded as the core fields of social policy.26,27 Until the 1970s, there was a general consensus that this period could be characterised as the golden age of the welfare state, with a notable increase in measures designed to enhance well-being.10 Subsequently, the advent of the oil crisis in 1973 precipitated a crisis in the welfare state, prompting a re-evaluation of its efficacy in addressing the old social risks for which it was originally conceived.27 From this point onwards, the term ‘welfare state crisis’ began to appear with increasing frequency in academic literature.28 Since the year 2000, the term “welfare state crisis” appeared a total of 148,792 times in academic publications.28 The recent period has witnessed a longer phase of the welfare state crisis than that of the Golden Age.29 The resilience of the welfare state is being tested as it faces the challenge of transforming itself to cope with the new social risks.25,30 This is because the state and politics are increasingly reaching their limits in dealing with the old social risks and are threatening to become incapable of acting.9,31

The existing literature addresses the question of whether the welfare state requires structural change, and, if so, to what extent.31 However, this topic is beyond the scope of this thesis. For the institutional context, this thesis focuses on the role of the market, more precisely on the businesses within social policy and the welfare state. The interrelationship of social policy, the welfare state and businesses are often neglected in academic research.27,32 There are several reasons why this presents a problematic situation. For instance, the literature suggest that businesses are capable to relief pressure from the welfare state through the implementation of occupational welfare (OW) measures.27,33-35 Additionally, workplace health and well-being practices have profound influence on the overall well-being of the population.36 This is especially salient in consideration of the rising ill-health in recent years.37

To provide a comprehensive overview over social policy and its corporate relations, a literature review is conducted. The thesis consists of a total of six chapters, the first one being the introduction. Chapter two presents the methodological approach employed. The literature review is based on elements of the methodology proposed by Brocke et al. (2009)38and Mitton, Manning and Vickerstaff (2011)39. Chapter three provides an explanation and definition of social policy and its key concepts, while also identifying the associated problems. Chapter four presents the historical context and development of social policy and the welfare state and discusses existing challenges. Chapter five provides an overview of the main fields of action, outlining the five primary areas in detail according to key aspects, objectives, implementation options and criticism. Chapter six examines the interplay between social policy and its core concepts and businesses and discusses measures for businesses to engage in the distribution of welfare.

2 Social Policy

2.1 Defining Social Policy

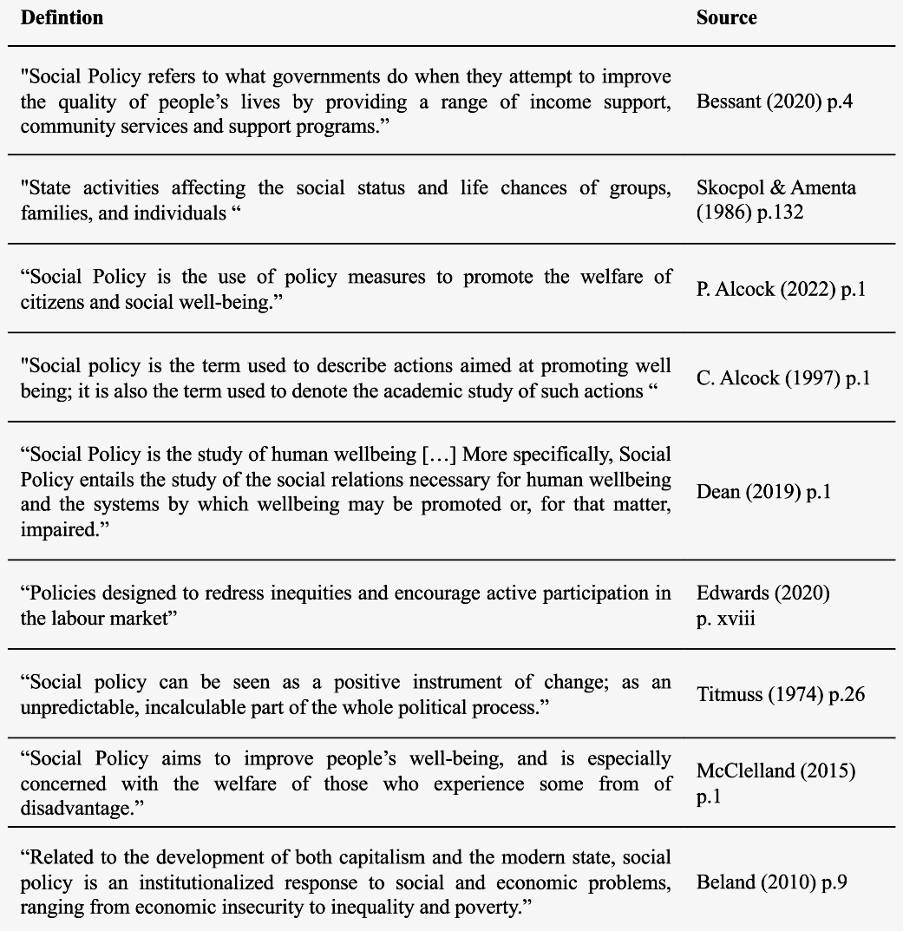

A uniformly accepted definition of the term social policy has not yet been established.1,2,7-12 The academic literature contains a considerable variety of definitions of social policy.7 The development of a common understanding of the term is therefore proving to be an tedious task.3 In this regard, it should be noted that some definitions are formulated so vaguely and imprecisely that they can be understood as general definition for sociology.41 To illustrate this point, Titmuss (1974)41 makes use of Macbeath’s (1957)42 definition, which defines social policy as follows:

“Social policies are concerned with the right ordering of the network of relationships between men and women who live together in societies, or with the principles whish should govern the activities of individuals and groups so far as they affect the lives and interests of other people.”42, p.1

In contrast, there are definitions that are very precise regarding the tasks and objectives of social policy and leave little room for interpretation. Althammer et al. (2014)8, for example, define social policy as:

“(…) political action aimed at improving the economic and social position of economically or socially disadvantaged groups through the use of appropriate means in line with the basic social and societal goals pursued in a society. Social policy therefore pursues two objectives: On the one hand, the promotion of the free development of the personality as well as basic social rights and obligations, and on the other, the guarantee of social security, social justice, equal treatment and protection against risks that could jeopardise livelihoods, whereby the latter can also be described as an ‘insurance function’.”8, p.4 (Translation by author of this thesis)

The range of possible definitions of social policy is greater than the two positions presented. The empirical diversity and the different definitions result in particular from the scope of social policy.7 Social policy represents an interdisciplinary field of study that draws on various scientific disciplines.1,3,13,24,43-45 In addition, the term social policy is employed in different ways.1,2,7,10,14,24,26,44,45 For example, it can be understood as a scientific discipline, as a measure or policy output, or as a process to improve social well-being.3,7,13,14 Ultimately, perspectives and their respective ideologies influence the understanding of social policy greatly and further contribute to the debate about what social policy is or should be.7,8,41 Although no standardised definition of the term social policy has yet been established, the concept can nevertheless be defined in more detail. This can be achieved by examining the various definitions and identifying the common themes and areas of divergence. The following table provides an overview of nine definitions of social policy.

A common element can be identified when analysing the definitional approaches, as a focus on the well-being of citizens is a recurring theme. This aspect is particularly emphasised by authors such as Dean (2019)2, Alcock (2022)26 and McClelland (2015)7. In defining social policy, Dean (2019)2 identifies social policy as a field of study concerned with the promotion of human well-being and the social relationships that facilitate this objective. McClelland’s (2015)7 perspective is further reinforced by the assertion that social policy is specifically designed to enhance the well-being of those who are disadvantaged in some way. These perspectives imply that social policy is not merely a set of measures, but rather a comprehensive system that aims to optimise the well-being of the population through targeted policy interventions, with particular attention to vulnerable groups.

Another common aspect is the essential role of the state as a principal actor. The definitions provided by Bessant et al. (2020)11 and Skocpol & Amenta (1986)46 emphasise that social policy is characterised by state activities aimed at improving the social living conditions of the population. It is thus deemed essential that the state intervene to address systemic inequalities and promote social justice.

Conversely, the definitions also demonstrate discrepancies that indicate varying focal points and approaches. For instance, Edwards et al. (2020)47 consider social policy as a means of promoting labour market participation, thereby adopting an economic perspective on social well-being. In contrast, Beland (2010)5 posits that social policy should be conceptualised as an institutionalised response to the social and economic challenges that have emerged as a consequence of the development of capitalism and modern states. Titmuss (1974)41 definition broadens the perspective by defining social policy as a positive instrument of change of the overall political process. This view emphasises the dynamic and often complex nature of social policy.

As previously stated, an examination of the definitions in isolation reveals a considerable degree of diversity in terms of content. The diversity can be attributed to several factors, which are elucidated in the following section. For the purposes of this thesis, social policy is defined as followed based on the aforementioned definitions: Social policy is a comprehensive system of institutional measures aimed at promoting the well-being of the population.

2.2 Scope of Social Policy

The multiplicity of definitions is a consequence of the comprehensive nature of social policy.7 Social policy cannot be reduced to a single academic discipline, but rather encompasses a broad spectrum of research subjects.3,12,13,24,43Additionally, it is characterised by ideological influences, which in essence imbue social policy with a particular meaning.11,13,41,48,49 Social policy also has a variety of meanings.1,2,7,10,13,14,24,26,44 However, in practice it is often used synonymously with other terms, resulting in a high degree of diversity in terms of content.50

In order to conduct adequate research of social policy, it is necessary to draw on a variety of different disciplinary perspectives.7 Due to the fact that the more comprehensive information on the production, distribution and consumption of welfare can be found in a variety of disciplines it is necessary to take them into account.7,12 The disciplines include sociology, economics, psychology, philosophy, political science and history.7,12,13,51 Sociology offers valuable insights into the structures of social relationships.7 This is a crucial aspect to social policy according to the definition from Dean (2019)2. Concurrently, economics offers a vital understanding of the distribution and efficacy of resources.7 Economics is indispensable for formulating policies aimed at rectifying inequities and fostering active involvement in the labour market, as Edwards et al. (2020)47 elaborated. The field of psychology examines individual behaviour, therebycontributing to the design of social policies that consider the diverse needs and well-being of citizens.7,12 As McClelland (2015)7 notes, particularly for those facing disadvantages. Philosophy engages with the values and goals that underpin social policies, discussing the ethical implications of concepts such as social problems or inequality, as evidenced by the definition provided by Beland.5,7,12 Finally, political science analyses the actions of the state.7 Which, according to Skocpol and Amenta (1986)46, affects the social status and life chances of various groups, families, and individuals.

The interdependence of economics and social policy is of particular relevance.7 The implementation of economic policy exerts a considerable influence on a number of key aspects pertaining to economic prosperity, including the levels of employment, the prices of goods and services, and the allocation of state funding.1,7,52 Concurrently, there is a growing acknowledgement that social policy can also yield economic advantages.7 The promotion of social and human capital is worthy of particular mention, as is the term social investment, which is also used in this context.1,7 A narrow perspective on economic policy that focuses exclusively on competition and market forces can result in social policy becoming a mere residual.7,8 In contrast, a comprehensive approach to economic policy considers not only market forces but also the well-being of citizens through the implementation of political measures.7,8

Social policy is understood in a variety of ways within academic discourse.1,3,7,10,12,26 In this context, it is useful to consider the definition proposed by Alcock et al. (2011)3, who distinguish between two key understandings of the term. Firstly, it is used to refer to the outcome of political measures in this area. Secondly, it is used to refer to the scientific discipline that deals with social policy.3

Baldock (2011)10 posits that social policy can be conceptualised as a product with distinct characteristics, shaped by the interplay of political processes. In this context, it is first necessary to define social policy as intentions and goals. In this sense, it encourages debate and the clarification of objectives, which may occur through political declarations or informal agreements.7,10 An alternative form to the analysis of social policy is to categorise it as administrative and financial arrangements. In this regard, the organisation of services and institutions is a relevant consideration to achieve the defined goals.7,10 These arrangements illustrate the practical implementation of social policy objectives, providing a comprehensive structure and funding for their realisation.10 Ultimately, social policy can also be categorised in accordance with its outcomes. Of particular interest are the outcomes on poverty and inequality, the treatment of different groups, and the general quality of life of the population.7 The results of social policy demonstrate the actual consequences for the well-being of individuals and is therefore of particular interest.10

The question of how social policy can be defined as a scientific discipline is the subject of considerable debate.8 The objective of social policy is to explain the reality of a given situation by analysing and simplifying the complex issues and concepts that are themselves the subject of debate. The objective of social policy is therefore to gain insights into social coexistence.8 The primary focus of scientific inquiry is the examination of the content of social policies, specifically the specific state measures that comprise them.12,26 Moreover, the evolution, administration, and implementation of the measures, as well as the motives and circumstances that led to their enactment, are subjected to examination and analysis.7 The objective of this research and analysis is to identify emerging social issues and the necessity for intervention. The assessment of the results and outcomes produced by the implemented measures allows for an evaluation of the extent to which the intended objectives of the measures have been achieved.8 This encourages debate about the necessity of direct measures and whether further measures are required or should be terminated.8 It should be acknowledged that the process itself is not value-free and that the discussions about the results and recommendations for action must be considered an integral part of it.8,12

The significance of social policy is contingent upon value judgments, as without these, the concept would lack any meaningful substance.41 The foundation for any value judgments is the perspective of the scientific and academic community, which in turn is shaped by an underlying ideology.8 Consequently, perspectives and ideologies form the intellectual basis for the actual debate on the focus and objectives of social policy.49,53 It is therefore crucial to engage with these. The ideologies and perspectives espoused by individuals and groups lead to disparate conclusions and results when the same topic is considered by actors in different fields, whether in politics or science.26,53 Consequently, the meanings ascribed to social policy, thus the policies themselves and the way they are examined and analysed, are significantly affected.49,53 It is of particular relevance here to understand that social policy is based on the underlying perspectives and associated ideologies.54

A review of the literature reveals a multitude of disparate perspectives and ideologies. As might be anticipated, there is considerable debate surrounding this topic, with no clear consensus emerging regarding the precise number of perspectives or ideologies, or the means of distinguishing between them.55 To gain an overview of the perspectives, this thesis will briefly consider the core arguments of the seven perspectives set out by the student’s companion to social policy. The theoretical perspectives to be considered are as follows: neoliberalism, the conservative tradition, social democracy, the socialist perspective, feminist perspectives, social movements, and postmodernism.

The neoliberal perspective espouses the values of individual autonomy, free market economics, and a minimalist approach to the role of the state in society. The argument is made that the welfare state system should be limited to eliminate bureaucracy and reduce taxes.56 In contrast, the conservative tradition advocates for a more prominent role for the state in economic and social matters. They prioritise a free market economic system while also underscoring the responsibility of the affluent to assist the less fortunate.57 The emphasis of social democracy is on combating injustice and reducing inequality through the utilisation of political majorities and the implementation of reforms to economic and social institutions.58 The socialist perspective posits that the free market and capitalism in general are detrimental to well-being. The well-being of the general public should take precedence over the fluctuating fortunes of the market. While the welfare state offers a number of advantages in terms of improving the general standard of living, it is nevertheless subject to criticism for exhibiting certain characteristics associated with capitalism.59 The feminist perspective argues that the welfare state both reinforces and constructs gender inequalities, and advocates for addressing gender inequality alongside other forms of oppression in the delivery of welfare and the understanding of social policy.60 The social movement perspective is characterised by three fundamental features: “conflict with an identified opponent, collective identity, and a network structure”61, p.92. The primary objective of these movements is to secure recognition for marginalised groups or issues within society, a goal frequently pursued through demonstrations and protests. However, social movements also engage in lobbying activities. While they may not consistently achieve their immediate objectives, they can exert significant long-term influence on societal structures.61 The postmodernist perspective is distinguished by a rejection of universalism and a conviction that truth is contextual. Additionally, they reject fundamentalism and essentialism, and refrain from making binary distinctions.62 They endorse the politicisation of identity and celebrate irony and otherness. One of the defining characteristics of postmodernism is its playful and ironic attitude, which often manifests in a refusal to take things too seriously, including the postmodernist perspective itself.62 However, this playfulness should not be mistaken for complacency. Rather, it should be seen as “a celebration of diversity, hybridity, difference, and pluralism”.62, p.101 Instead of engaging in debates about what is real, the focus is on supporting each other in continuously rebuilding our understanding of society.62 The goal is to foster solidarity, rather than to discover absolute truth.62

Ideologies exert a significant influence on the formation of social policies and the allocation of welfare benefits.63 The perspectives and ideologies diverge based on the beliefs held regarding the role of the state or the individual in welfare provision, the underlying understanding of collectivism or individualism, and the preferences for market-led or state-led solutions.55 These ideological distinctions are fundamental to an understanding of the influence of different ideologies on the design and delivery of welfare services.63 Ideologies exert a profound influence on the role of the state in organising and providing welfare services, and have a significant impact on the political process, particularly in the context of social policy.63 Furthermore, ideologies not only influence the range and design of welfare state services but also impact ongoing discussions on the effectiveness of state intervention to address social issues.55,63 This thesis finds it evident that ideologies play a significant role in both defining policy objectives and evaluating their success.

In conclusion, this thesis finds that the field of social policy is inherently characterised by a high degree of complexity and multi-layeredness. This is because a number of academic disciplines, ideological influences and definitional ambiguities play a role in shaping social policy and must be harmonised with one another.7 An interdisciplinary approach is the only means of attaining a comprehensive understanding of social policy.7 The ideological foundations of social policy add another layer of complexity to its analysis, as different perspectives offer varying views on the role of the state, the market and the individual in the provision of welfare. These circumstances not only influence the formulation and implementation of social policy measures but also the criteria by which their success is evaluated.26,53 Social policy can therefore be characterised as a dynamic and contested field, deeply embedded in value judgements and ideological debates, reflecting the diversity of thought and complexity of social issues.12 The lack of clarity surrounding the concepts in question is further compounded by the fact that they are frequently used synonymously, with terms such as social policy and welfare state often being employed interchangeably.50 As part of a discussion about social policy, it is therefore necessary to examine this issue in greater depth.

2.3 Social Policy and the Welfare State

In the context of social policy, it is crucial to comprehend the concept of the welfare state, as it is fundamentally intertwined with social policy.11 While the terms are often used interchangeably, they are distinct concepts.11 Social policy influences and overlaps with the welfare state, with both focusing on well-being, distribution, and state intervention for the benefit of individuals.15 The welfare state provides the institutional context for social policy and plays a significant role in various aspects of society, including the economy.15 However, there is still some debate over the exact definition of the welfare state, leading to a lack of consensus and empirical diversity in its understanding.16 This lack of clarity is seen as advantageous in politics but a disadvantage in academic discourse.54 Consequently, there is no universally accepted definition, resulting in a mosaic of definitions and perspectives.17,24 To gain a broader understanding, it is necessary to explore the diverse definitions and conceptions of the welfare state. Although there is no universally accepted definition of the term welfare state, an approach to analysing this concept is to examine the various definitions and concepts that have been proposed to gain an overview with the objective to identify similarities and differences between them.

The definitions of the welfare state presented in the table illustrate the disparate perspectives and emphases evident in the academic literature. Pierson (1988)64 places emphasis on the redistribution of opportunities, which he identifies as a fundamental responsibility of the state. The state engages in active intervention in economic production and distribution processes with the objective of reducing inequalities between individuals and social classes.64 Cass (1998)65 puts forth the proposition that the state should act as a safeguard for individuals against the adverse effects of unregulated market processes. Esping-Andersen (1990)19 characterises the welfare state as being primarily concerned with the production and distribution of social prosperity. In contrast, Briggs (1961)23 places greater emphasis on the implementation of measures designed to guarantee a minimum standard of living for all citizens, irrespective of their financial means or social situation. In this context, the role of the state as guarantor of social security and equal opportunities is of particular significance. The literature emphasises that the welfare state is responsible for both the fulfilment of recognised social needs and for intervening in the market economy to meet people’s basic needs.66 The definitions put forth by Baldock (2011)10 and Bessant et al. (2020)11 focus on government expenditure on welfare, a perspective that has been the subject of criticism within the academic community.19 This approach is inadequate in that it fails to acknowledge the multifaceted nature of the welfare state, which is shaped by the interplay of three key actors: the state, the market, and the family.19The aforementioned factors are not considered in the definition provided, which results in an incomplete and one-sided assessment of state expenditure.

As evidenced by the definitions, the state plays a pivotal role in shaping the welfare state. However, academics such as Fitzpatrick (2011)14 have highlighted that the free market has recently emerged as a significant factor. This is also evident in the definitions. The increasing influence of other sectors has prompted a shift in discourse.14 Resulting in a growing emphasis on alternative terms like welfare system.10 Another example is the term welfare regime, which offers a more nuanced understanding of the complex interplay between state, market and family actors in the delivery of welfare.19 This approach moves beyond a narrow focus on government and government spending, as emphasised in the definitions of Besant et al. (2020)11 and Baldock (2011)10. In consideration of the preceding definitions, this thesis argues that a welfare state is a welfare system with the objective of enhancing the population’s well-being. This is achieved through a complex welfare system, consisting of the state, the market, and the families.

As previously outlined, social policy can be defined as a comprehensive system of institutional measures designed to promote the well-being of the population. This definition illustrates that the welfare state, comprising its three key actors – the state, the market, and the family – serves as the institutional foundation within these measures are implemented. These measures encompass a vast array of domains and are inherently intricate.1,10 In the literature, these measures are often considered in the context of fields of action.1,10 Bessant et al. (2020)11 provide a more detailed account of these fields of actions, noting that the activities of the welfare state encompass the domains of health, welfare, education and housing. The chapter five provides a comprehensive examination and presentation of the measures that occur within this context.

2.4 Welfare State Typologies

The advent of the concept of the welfare regime provided a novel opportunity for comparative research on the diverse forms of social welfare systems across different national contexts.19,20 The foundation for this research topic was laid by Titmuss, who, however, never provided empirical evidence for his typology.9,20 Esping-Andersen (1990)19 built on this typology and achieved a significant breakthrough with his work, Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism.9 He successfully empirically analysed the typology.9 Esping-Andersen’s (1990)19 typology is based on the concept of the welfare state regime.20 This work marks the beginning of a debate on comparative welfare state theory that continues to this day and is considered a defining moment in welfare state research.20

Esping-Andersen (1990)19 posits that the level of benefits alone is an inadequate criterion for defining the welfare state. He puts forth a respecification of the concept, with a particular emphasis on three criteria: decommodification, stratification, and the relationship between the state, market, and families.19 The term decommodification is used to describe the extent to which the welfare state enables individuals to become economically independent of the market. Such determinations are made based on factors including benefit regulations, income replacement ratios and social entitlements.9,19 The examination of stratification considers the impact of the welfare state on social inequality, distinguishing between means-tested benefits, social insurance models and universalist systems.9,19,20 Through empirical analysis, Esping-Andersen (1990)19 identifies three clusters of welfare states, namely liberal, conservative, and social democratic. It is important to note that these ideal types do not exist in their pure form; rather, real welfare states exhibit a degree of approximation to these types.9,20 The liberal type is distinguished by the presence of means-tested benefits and a relatively low emphasis on universal and social security benefits.20,21 The state’s role is to facilitate market activity and to mitigate the decommodifying impact of social benefits.9,21 Ulrich (2005)9 states, that countries such as USA, Canada and Australia could be assigned to the liberal type according to this typology. The conservative type, exemplified by countries such as Germany, Austria, and France, prioritises social security while maintaining the distinction between social classes and traditional family structures.9 The role of private security is of minimal consequence, and vertical redistribution is constrained.9,21 The social democratic type, which is predominant in Scandinavian countries, combines decommodifying and universal programmes with the objective of maximising individual independence from both the market and the family.20 These countries give priority to the interests of the emerging middle classes.9,20 The group of social democratic welfare states is relatively small, with the Netherlands representing a notable exception.9

The publication of the work had a significant impact on the academic community, prompting extensive discussion, further research, and numerous tests.20 It also served as a foundation for adapting and developing further typologies.20 Despite the emergence of diverse empirical approaches to welfare state research, the three types proposed by Esping-Andersen (1990)19 remain a prominent framework in the field.20,21 For example, recent works, such as Aspalters’ (2023)67 Ten Worlds of Welfare Capitalism, builds on the work of Esping-Andersen (1990)19. The typologies of welfare states demonstrate that focusing on the state and state spending as the sole solution strategy is not an expedient approach.19Rather, a holistic approach that encompasses the market, family, and state actors is required.19 The weighting and responsibility of individual actors varies depending on the type of welfare state in question.9 Nevertheless, it can be deduced that these actors interact in a complex network of relationships, which is referred to as the welfare regime.20Furthermore, it is evident that the term welfare state is a misnomer, given the existence of a multitude of distinct welfare states.18 This makes the task of developing a unified conceptualisation of the welfare state particularly challenging.

The close interdependence of social policy and the welfare state, coupled with the fact that the latter provides the institutional context for the former, necessitates an examination of the historical evolution of both concepts collectively.

3 Historical Context

In examining the historical development, it is essential to consider the underlying definition, as this provides a foundation for a comprehensive and accurate discussion.9 In accordance with Skocpol & Amenta’s (1989)46 definition of social policy as “state activities that influence the social status and life chances of groups, families, and individuals”46, p.132, it can be inferred that social policy has existed since the early formation of the state. Considering the definition of social policy as a comprehensive system of institutional measures aimed at promoting the well-being of the population, it can be proposed that the grain dole implemented by Augustus in the Roman Empire exemplifies this definition and represents the origin of social policy. The grain dole was designed with the objective of guaranteeing the food supply for the economically disadvantaged population through the subsidised or sometimes free distribution of grain throughout the Roman Empire.22

The key differentiating factor between contemporary state social policy and its historical antecedents is the explicit acknowledgement of the state’s obligation to promote the well-being of its citizens and the implementation of corresponding social security measures in the form of a safety net.9 This recognition of state responsibility can be further observed in historical examples such as the Prussian Land Law of the late 18th century and the English Poor Law of the 16th century, which may be considered a possible approach to the origin of modern state social policy.9 Nevertheless, there is a consensus that the concept of modern state social policy, in the narrower sense, is a relatively recent phenomenon.9,23

It is difficult to ascertain the origin of social policy due to the lack of a widely accepted definition of the term and the resulting lack of consensus regarding its historical emergence.9,25 Bessant et al. (2020)11 identify the difficulties associated with defining social policy, noting that it is a concept that is also the subject of numerous discussions and controversies. They put forth the proposition that concepts have an origin and an evolution that exert an influence on the discourse surrounding them. In the absence of consensus on the origin, it is not possible to establish a single definition, and without such a definition, it is not possible to reach a consensus on the origin.11 Nevertheless, indications of the origins can be found on numerous occasions within this context. For example, the introduction of the poor law in England, the introduction of accident insurance under Napoleon III, the introduction of veterans’ pensions in the United States, and the introduction of social insurance in the German Empire in the 1880s.9

It can be stated that the debate on the origin of welfare states has a significant focus on the European area.25 Particularly in relation to the formation of the welfare state in the United Kingdom.68-70 In this context, the term established welfare states is frequently employed in the literature within the OECD.25 Conversely, the term emerging welfare states is employed to describe those in the global South and East.25 This study is limited to an examination of the historical context of established welfare states, as a more comprehensive analysis would exceed the scope of this thesis.

It is not possible to identify a single origin for social policy and the welfare state within the OECD area. Rather, the welfare states within the various nations developed in a manner that was somewhat independent of one another.71However, each nation strives to present itself as the originator of social policy and the welfare state.9 Nevertheless, despite the independent development of these states, there are identifiable overarching trends that emerge in the period following the Second World War.18 This includes the period from 1942 to 1973, which is often referred to as the Golden Age, and the Welfare State Crisis from 1973 onwards, which persists to the present day.31

The precise origin of the welfare state cannot be ascertained with certainty.9,25 Alcock (2011)26 offers a more precise understanding of the origin of the classic welfare state, situating it in the 1940s in alignment with the published Beveridge Report. In contrast, Bessant et al. (2020)11 offer only a rough date, placing it in the 18th century, and generally refer to the European region. While Kuhlmann (2018)25 and others employ a similarly precise approach, there remain discrepancies in terms of the geographical context and the chronological classification of the origins. Kuhlmann (2018)25 dates the inception of the welfare state to 1601, when the Poor Law Acts were enacted in Great Britain. In the academic literature, there are also approaches that situate the origins in the context of social insurance in the German Empire in the nineteenth century, which was introduced under the leadership of Bismarck.9 Although systems to guarantee welfare had already been developed in earlier times, particularly in the family, the church and the individual community.9,25

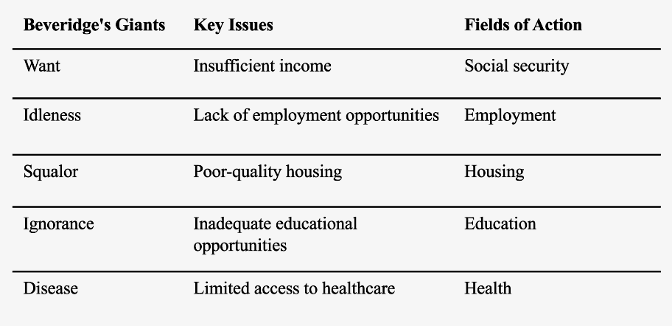

The Poor Law, which originated in 1601, is often regarded as the forerunner of the modern welfare state.9,25,26 The exact origins of the modern welfare state is a topic of considerable debate.9,16 The period of industrialisation in the late nineteenth century can be identified as the starting point.9,10,25 The following century saw the further development of welfare states and the dissemination of the concept.9 Despite the diversity of these welfare states in terms of their attributes, commonalities can be identified, Garland (2016)18 states that when “viewed cross-nationally […] the presence of large-scale historical processes that were reshaping social, political, and economic landscapes all across the developed world”18, p.28. It is of paramount importance that these welfare states are able to adapt to newly emerging events and continue to develop.25 In this context, the period following the Second World War is of particular interest. In the UK in 1942, the Beveridge Report was published, which addressed the necessity for a comprehensive reform of social security.25,26 The Beveridge Report identified five significant social issues; want, idleness, squalor, ignorance, disease.1,26 In consequence of these issues social reforms were implemented between 1945 and 1951.26 Consequently, a series of measures were introduced with the objective of guaranteeing every citizen free access to education, establishing the National Health Service, making a state promise to guarantee full employment, providing public housing for all citizens and creating a national insurance scheme for all citizens in emergencies.26 This resulted in a notable increase in the scope of government obligations and expenditure.1,26 In the literature, this period following the Second World War is frequently designated as the Golden Age of the welfare state.10,25,68 This development can be attributed to an expansion of the welfare state and general economic growth during the period in question.10,25 During this period, there was a growing consensus that the focus should be on the creation of a safety net for citizens, designed to compensate for the social risks commonly referred to as the old social risks, including unemployment, old age, illness, disability, childbirth and child rearing.72

The 1973 oil crisis constituted a turning point in the history of the welfare state.25 The crisis resulted in a financial crisis, which in turn led to a reduction in welfare state spending and measures.9,25 During this period, an academic discourse commenced concerning the financial viability and capacity of the welfare state to address the old social risks.29,31Subsequently, the globalisation in the 1990s, the global economic crisis of 2007, the climate emergency and the Coronavirus pandemic served to further fuel debate, with a total of 148,792 papers published from 2000 onwards that included the search string ‘Welfare State Crisis’.28 While the crises themselves were not the result of the welfare state, they gave rise to new social risks that placed an increasing burden on the welfare state.29 The new social risks include demographic change, migration, climate change and structural changes in the labour market.25,73

The management of the old social risks, that is to say the traditional social risks, presents the state and politicians with challenges that impair their ability to act with regard to the equally relevant but new social risks.74 This is exemplified by the financial expenditure. To date, financial support has been allocated to measures addressing the old social risks at a significantly higher level than to measures addressing the new social risks. In this regard, a markedly smaller proportion of financial resources is allocated.74

Despite the resilience of the welfare state in the face of external pressures of the past, the current challenges it faces are considerable.31 The existing literature addresses the question of whether the welfare state requires structural change, and, if so, to what extent.30,73 However, this topic is beyond the scope of this thesis. For the institutional context, this thesis focuses on the role of the market, more precise on the businesses within the welfare state. The objective is to investigate measures that companies could implement to alleviate the pressure on the welfare state in its current crisis. In line with the definition of social policy outlined above, the measures taken by employers represent institutional measures aimed at enhancing the well-being of the population.

4 Fields of action

It is evident that social policy is multifaceted, encompassing a vast array of field of actions each with their unique characteristics and objectives.1 Hudson et al. (2015)1 argue that the five giants that emerged from the Beveridge Report constituted the foundation on which the fields of action were later established. This is illustrated in table seven. While these fields of actions do not represent a comprehensive overview of all fields of actions, they provide a valuable basis for understanding the latter.1 Given the significant national variations in the fields of action, it is not feasible to adopt an overarching perspective on all of them in this context. 1

It is important to note, however, that the authors typically present their perspectives on the fields of action from a national standpoint.1 As the majority of the literature is either from the OECD area and especially from Britain, or deals with topics from these countries, there is considerable bias noticed.24 The diversity of social problems, ideological discourses, and contextual challenges makes it challenging to develop a standardised structure for the individual fields of action.1Consequently, only the core aspects, objectives, implementation options, and criticisms of the fields of action are addressed to facilitate the development of a reasonably organised and stringent argument.1

4.1 Employment

The primary objective of employment policies are to achieve a high employment rate while ensuring that working conditions are decent.1,75 This entails the prevention of discriminatory practices based on factors such as ethnicity, gender, and religious beliefs.1 There are two principal approaches to achieving this goal, which may be categorised as supply-side and demand-side measures.1,76 Supply-side measures are designed to increase the number of individuals seeking employment, whereas demand-side measures seek to establish conditions that will result in the creation of additional job opportunities.1,76

One example of a demand-side measure is South Africa’s Expanded Public Works Programme, which was implemented in 2003. The objective of this initiative was to create 750,000 jobs by providing government funding for infrastructure projects in urban areas.1 Another example would be the German ‘Kurzarbeit’(short-time work) system, a program that helps protect jobs during economic downturns by providing wage subsidies to companies that reduce working hours instead of laying off workers.77 It is noteworthy that the state plays a significant role as a major employer through the provision of public services in sectors such as healthcare and education.1 Nevertheless, a considerable number of countries tend to prioritise supply-side measures, which can be implemented in a variety of ways.1,76 Some supply-side measures concentrate on enhancing the overall appeal of work.1 This may entail the refinement of family policies, particularly in regard to women, through the provision of reliable childcare and parental leave, or the implementation of incentives that facilitate a harmonious work-life balance.1,27,78 Such measures have a beneficial effect on the reintegration of individuals into the workforce, they are provided by the employer and are referred to as OW.33,79Conversely, supply-side strategies may also entail the diminution of the appeal of unemployment.1,80 To illustrate, the provision of financial assistance to the unemployed may be withdrawn in the event that suitable employment opportunities are declined.1 Nevertheless, employment measures also present certain difficulties.1 It is frequently the case that an increase in the quantity of jobs available will result in a reduction in the quality of those jobs.1 The implementation of social security measures may result in a reduction in the labour force, which is contrary to the objective of enhancing employment opportunities.1 The efficacy of active labour market programmes is constrained by the necessity for labour supply to correspond with market demand.1,81 A further issue is that higher-paying jobs are more likely to be available to individuals with higher levels of education and skills, while those with lower qualifications are less able to escape poverty through employment.1 One potential solution is the implementation of a minimum wage.1However, the challenge lies in determining the appropriate level of minimum wage, given the significant variations between countries, with Romania having a minimum hourly wage of 0.62 euros and France having a minimum wage of 8.27 euros in 2012.1

4.2 Social Security

Social security represents a fundamental component of the welfare state, with the principal objective of furnishing financial assistance to individuals who are unable to generate income due to a range of risks and contingencies, including unemployment, advanced age, illness, disability, and other factors.1,82-85 The primary objective of social security is to safeguard the income of citizens, typically through the provision of cash transfers.83,85 Nevertheless, the level of expenditure on social security does not necessarily reflect the comprehensiveness of the system.1 To illustrate, countries with a higher gross domestic product, such as Hong Kong, may allocate a smaller proportion of their budget to social security compared to countries with a lower gross domestic product, such as Mongolia.1 There are various methods of implementing social security payments, including means-tested, universal, and insurance-based benefits.1,83,84 Means-tested benefits are provided to citizens who meet the specified criteria and have income levels below the defined threshold.1,83,84 In contrast, universal benefits are granted to all citizens who meet the requisite eligibility criteria.1,83,84

Lastly, insurance-based benefits are calculated based on the individual’s contributions to an insurance fund.1,83 Once the individuals eligible for social security payments have been identified, a further distinction must be made in regard to the manner in which the amount of the payment is determined.1 There are two principal methods: earnings-related and flat-rate.1 In the case of earnings-related benefits, the individual’s previous income is considered, with a proportion of their previous salary serving as the basis for the payment.1 To illustrate, in Sweden, an individual who becomes unable to work would receive 52% of their previous salary.1 Conversely, flat-rate benefits provide a uniform amount to all eligible individuals.1 While the state plays a significant role in providing social security, other factors, including the market and family, also contribute to this process.1 In particular, the provision of pensions is closely connected to both employment and the market, while families often provide support in this regard as well.1,83,84 Despite the impact of social security in reducing poverty and inequality, it is not a solution that can entirely eliminate these issues.1

4.3 Health

The primary objective of healthcare policy is to guarantee that all individuals have access to suitable healthcare, encompassing both treatment for illness and routine examinations.1 In the majority of countries, the government assumes a prominent role in the financing of healthcare, with a considerable proportion of public funds allocated to the healthcare system.1,73,86 Healthcare systems are typically characterised by a combination of public and private provision and funding.1,86,87

In the public funding approach, the government generates healthcare funding through taxation, without the establishment of a separate fund dedicated solely to healthcare.1,87 This provides the government with flexibility in the distribution of funds, enabling adjustments to the healthcare budget without the necessity of altering healthcare taxes.1 An example of this is Canada’s Medicare system, which provides universal health coverage funded through taxes.1 All necessary medical services are covered in this type of health care service, without direct out-of-pocket payments.88 This ensures that healthcare is accessible to all citizens.88 However, this also means that healthcare spending can be readily reduced by governments with anti-establishment agendas.1 In the service provision method, the state establishes more stringent regulations and greater control over the allocation of healthcare funds.1 A significant number of Western European countries have introduced social health insurance funds, whereby a proportion of citizens’ income is paid into the fund.1In Germany, for instance, the legal requirement in 2012 was that an average of 7.55% of income had to be contributed to these funds, with employers also contributing.89 In addition to collective or social mechanisms, private health insurance represents another option for those requiring health coverage.1 In the context of private insurance, individuals are required to pay a premium in exchange for coverage that is tailored to their specific needs.1,87 Such an arrangement offers advantages to those who are relatively healthy, who may receive more favourable terms and lower premiums.1Nevertheless, those with poor health or chronic illnesses may be required to pay higher premiums.1 An exemplar of this type of healthcare funding is the United States.1 Private insurance is frequently regarded as a supplementary or supportive option in conjunction with the public healthcare system.1,87

The cost of healthcare services is increasing due to technological advancements and demographic changes.1,87 In response, governments are seeking to rationalise healthcare services in order to meet this growing demand and reduce costs.1 However, one of the major challenges in healthcare is the existence of inequalities in access to healthcare services, which only serve to further contribute to these disparities.1,86 Overall, the complexity of healthcare systems and the need to balance access and affordability pose ongoing challenges for healthcare policy.1

4.4 Education

Access to education is not only a valuable asset, but also a fundamental human right.1 Education has social, cultural and economic goals.1,75,90 It also plays a major role in terms of employment, as it can boost the economy and achieve labour market participation through educational measures.1,75,91 Although there is no universal definition of education, it is generally divided into primary, secondary and tertiary.1

Education serves not only to pursue social goals and create opportunities for social participation, but also to strengthen social cohesion.1,90 Furthermore, education is instrumental in developing human capital, which encompasses preparation for the labour market.75,90,92 The relationship between education and the economy is becoming increasingly intertwined, largely due to the fact that investment in education constitutes a significant portion of social expenditure.1 Nevertheless, these investments are expected to yield returns in the form of human capital, which can be conceptualised as a form of social investment.1,90,92 In this regard, one area of contention is the assertion that the qualifications conferred by education should align with the demands of the labour market.1 If education policy addresses this issue and aligns the provision of education with the demands of the labour market, this represents an expansion of the employment field of action.1

Another significant objective of the educational system is to ensure that all individuals have an equal opportunity to succeed.1,75 However, the issue of social mobility, the ability to move between social classes, raises concerns.1,92 The education system may be perceived as biased in favour of individuals from higher social classes, which could result in further advantages for them.1 It is important to consider the issue of equality of outcome, that is to say, the actual impact of these measures on equality.1,92

There is a lack of consensus at the international level regarding the realisation of these goals and the optimal structure of the education system.1 The German educational system, in particular the dual system at the tertiary level, which combines vocational training with classroom education and practical work experience, is designed to align educational outcomes with labour market needs.93 In contrast, the Finnish system is focused on equity and quality. It is free at all levels and provides small classes and highly skilled teachers, resulting in high educational outcomes and low disparities.94

4.5 Housing

The availability of a safe and secure place to live has a substantial impact on an individual’s overall well-being and health.1,95 It represents the nucleus of our lives and plays a pivotal role in the formation of our identity.1 It is therefore also a significant area of focus for social policy. In contrast to the other domains of social policy, the predominant actor in the housing market is the private sector, rather than the state.1,96 In this context, it falls upon the state to ensure an adequate supply of housing.1

Furthermore, it is essential to guarantee the quality of the housing. A substandard housing situation has a negative effect on health and well-being.1,95 Income-related poverty frequently gives rise to poor housing conditions, which in turn engenders social exclusion.1 Moreover, it is imperative to guarantee the affordability of housing, thereby ensuring that all individuals have access to adequate and secure housing.1 One illustrative example is the German ‘Sozialwohnung’(council house) programme, which provides affordable housing to low-income individuals and families.97 In contrast to the other fields of action, there is a paucity of mechanisms.1 In addition to the private market, there is also the public market, in which the state or state institutions purchase housing units with the intention of offering them for rental or sale.1,95 In this context, two options for housing are available.1 Housing can be owned or rented.1

In the event that neither of the aforementioned options is applicable, or if the state has failed to guarantee the availability, adequacy and affordability of housing, there is an inherent risk of homelessness.1 There are four types of homelessness: homelessness if one has no accommodation for the majority of the day, homelessness if one only has a temporary place to stay, homelessness if one lives insecurely, for example if one lives without a legally valid tenancy agreement, lives with friends and family temporarily, or occupies houses that are not liveable.1,98 Those who are about to have their accommodation demolished, and those who live in unsuitable conditions due to factors such as domestic violence, are also included in this category.1 Finally, those who live in inadequate housing are classified as such if they fail to meet the government’s requirements, for example, by living with a caravan on an unmarked pitch, in an overcrowded situation, or otherwise occupying a space that is not in accordance with the relevant regulations.1

The most significant challenge in housing policy is the need for the state to achieve a balance between public and private concerns.1 This makes it challenging for policymakers to implement housing policies in a timely manner without infringing on the rights of property owners.1,99 An illustrative case is that of Singapore, where conventional residential edifices and plots have been supplanted by skyscrapers to facilitate the construction of additional housing.1 Concurrently, a discourse pertaining to the environmental sustainability of development arises with respect to the question of whether, in the absence of housing, the surrounding uninhabited and/or underdeveloped lands ought to be developed.1

However, even when the aforementioned issues are considered, additional debates may emerge. For instance, it is argued that a reduction of housing shortages may be achieved through the restriction of immigration.1 In systems where home ownership is prevalent, renting can contribute to the segregation of different income groups in different neighbourhoods.1Consequently, it is crucial for housing policies to determine the optimal balance between home ownership and renting.96

5 Social Policy and its Corporate relation

The interrelationship between business and social policy, and the implications thereof, is a topic that has been insufficiently explored in academic research.27 There are notable deficiencies in the examination of the role of business in delivering welfare.27 It is argued that businesses are involved in a number of fields of actions of social policy, including education, housing, health, social security and employment.27 However, business entities have a distinct interest in engaging with social policy in the domain of employment.1,27 Accordingly, this thesis will primarily concentrate on the implementation of measures by businesses that are related to the field of action of employment.

Conversely, social policy can exert influence on businesses through its measures, as they contribute to the training of the next generation of workers through measures in education.1,75,90,91 By implementing healthcare measures, social policy ensures that employees are less absent due to illness.27 Nevertheless, the impact of social policy on businesses and labour market participation is not always beneficial and can also result in adverse outcomes.1,100 An increase in the level of unemployment benefits may result in a corresponding decrease in the number of individuals seeking employment.101 In particular, social policy is said to have positive effects in the context of social investment with regard to labour market participation, as it ensures that jobseekers can participate in the labour market again through retraining measures.102Despite the ongoing debate surrounding the impact of social policy on the economy, the labour market and therefore businesses, there is a growing consensus that social policy has a positive effect on the aforementioned.103

An increasing number of businesses are seeking to actively engage in social policy and deliver welfare, motivated by considerations of corporate image and competitiveness, as well as recruitment.27 This is achieved through, for example by delivering OW or by implementing workplace health and well-being practices (WHWPs), which will be discussed in chapter 6.1 and 6.2. Businesses may also engage with the policy process through lobbying, participation in government bodies, or through sponsorship and funding.27 The extent to which businesses participate in the policy process is contingent upon the policy in question, the area of interest, the perceived necessity of intervention, and the availability of resources.27 If the policy in question has a direct or indirect influence on the business’ costs, for example by influencing labour costs such as minimum wages or the provision of labour, the interest is considerable.27 It is generally observed that larger businesses have a greater interest in participating in the policy process, given that they tend to plan for the longer term and thus stand to benefit more from education and training measures than smaller, more short-term oriented businesses.27 While businesses have a greater influence on social policy than other groups, this influence is highly complex and comprises both direct and indirect factors. Direct influences include those previously mentioned, while indirect influences result from structural factors such as market power or investments, including in human capital.27

5.1 Welfare State and Corporations

The welfare state is facing an increasing risk of unemployment as a result of employers shifting their investments abroad.90 This is occurring concurrently with the fiscal crisis currently being experienced by the welfare state and represents a further burden on it.90,91 The taxation of businesses is also becoming an increasingly significant factor in this context. An increase in financial burdens on businesses can result in the relocation of investments or an increase in unemployment.90 Furthermore, the potential for outsourcing is compounded by the consistently rising wage level that the welfare state is imposing.90,91 The threat of unemployment is particularly acute for many low-skilled workers, who are at the lower end of the wage scale. This reinforces social inequality and highlights the need for the welfare state to combat this through further redistribution.91 While social policy contributions may impose certain burdens on businesses, social policy measures provide social benefits that help stabilise overall demand for sales and employment. These benefits include an efficient labour force and a high degree of social harmony within and outside businesses, the latter of which is an important advantage for businesses.8 It is for these reasons that business owners argue that the state should refrain from excessive intervention in the labour market, as such regulation has a detrimental impact on competitiveness.48

The role of voluntary OW initiatives is significant. Scholars, such as Titmuss (1963)104 already pointed out, that OW is a component of the overall distribution and production of welfare.105 It is argued, that OW as a provider of welfare, is an important component in the transformation and change of the welfare state and should be seen as an alternative that can relieve the welfare state.27,33-35 OW is defined as “(…) non-wage provision that increases well-being of employees at some cost of the employer.”27p.151 The definition of OW is centred on the well-being of employees.48 It therefore shares a central aspect with social policy, the improvement of well-being. In addition, OW is seen as a way of combating social risks associated with the workplace.27 Thus, parallels can also be recognised with the welfare state, which combats the social risks of its time.27

Despite the evident benefits to the welfare state of initiatives designed to enhance occupational well-being, there is still a paucity of knowledge regarding these initiatives, even compared to the limited understanding that existed in the 1950s.48 This is evident by the fact that even “the role of the firm in setting and delivering social policy has been a subject that has been largely overlooked in scholarly writings about private sector social policy.”92p.27 The same applies in the case of OW, despite its increasing role in delivering welfare, it is often neglected in the social policy literature.27,33-35,79Nevertheless, the following provides an overview of the measures available to employers, criticisms of the concept, and the role that the state could play.

OW is observed to manifest in diverse forms. However, for the purpose of providing a comprehensive overview, all measures that are either partially or fully paid for, supplied, or provided by the employer are considered.79 Measures that aim to provide for old age, illness and incapacity for work, or that contribute to improving the family situation, such as the provision of childcare at work or the provision of flexible working hours, appear with greater frequency.27,33 In consideration of flexible working hours, there has been increasing evidence in recent years, that the concept of work itself is changing, with the emergence of more flexible forms of employment.75 A disadvantage of flexible working hours or part-time work is that the pay is insufficient to maintain a standard of living that can support a family.75 In addition, an increase in working hours has been linked to an increase in stress and health problems, as well as a negative impact on family life.75 However, there are flexible working time concepts, including the 4-day week, which address this issue and reduce working hours for the same pay.106 A recent study has shown, that reducing working hours without decreasing pay had positive effects on the work-life balance, with 54% of employees finding it easier to balance work with household tasks, sixty percent of respondents indicated that they were better able to fulfill their care requirements, while 62% indicated enhanced ability to engage in social activities.106 The evidence suggests that such initiatives can confer benefits to employers as well. There was a 57% reduction in employee attrition and an increase in business revenue. 106

However, OW’s measures extend beyond this to encompass financial well-being measures, including financial literacy training and debt counselling.79 Further examples include company-subsidized access to fitness facilities.79 Bahlsen, among other businesses, employs the services of Hansefit, a subcontractor, to facilitate access to fitness and sporting activities for its employees.107 OW further includes measures for education and training, such as paid training or company coaching programmes.79 Measures for housing, such as financial support for the purchase of a property or the payment of a deposit.27,79 Measures related to transportation, including the provision of a company vehicle, vehicle leasing, or the provision of public transportation tickets are included as well.79 Such measures enhance the well-being of employees, while conferring benefits upon employers.27 For example, effective OW can foster employee loyalty and retention through long-term initiatives such as a company pension scheme.27

One point of criticism regarding this aspect is the assertion that OW addresses solely the social risks faced by the workforce, which may inadvertently contribute to further social inequality and the division of societal groups.108,109These inequalities can be observed in the distinction between employees and non-employees, as non-employees are not beneficiaries of OW.109 Moreover, disparities can be identified within the employment context, as working hours, remuneration, and the nature of the employment context, influence the extent and type of OW delivered.33,109Furthermore, OW varies depending on the specific context of the employing company. Consequently, it is more probable that an individual will benefit from OW as a qualified permanent employee in a large business than a self-employed individual or as a temporary worker in a small business.33,110

The question of whether and to what extent the government should intervene in OW is a matter of considerable debate.27 For instance, the government may mandate certain OW measures, which could impose a financial burden on the company in question. Alternatively, it could create financial incentives, such as tax benefits, for businesses to voluntarily offer OW measures.27

Promoting OW can relieve the welfare state financially, through a reduction in tax expenditure on unemployment and an increase in tax revenue.80 However, it is argued that governments have an interest in promoting OW, as it relieves the burden on the welfare state and shifts it to employers.27 This should be viewed with a degree of scepticism, as a transfer of responsibility could potentially result in a shift of blame and a gradual erosion of the welfare state.35 This hidden dismantling could occur in two ways. Firstly, the state may reduce its own programmes and provide funding for the employer to assume responsibility, although the employer may lack the capacity to do so in a sufficiently generous manner.33 The second possibility is that the state does not reduce its programmes but relies more on OW from the employer. This would result in a reduction in state programmes during periods of economic downturn.35

5.2 Well-being and Corporations

“In the face of global epidemics of mental ill-health, the future of social policy lies with promotion of public well-being.”37, p.567 Although social policy is responsible for promoting well-being, it seems to be failing in this area.37 Authors, like Schulte (2010)36 and Vainio (2010)36 argue, that “well-being is a term that reflect not only on one’s health but satisfaction with work and life”.36, p.422 Since humans spend the majority of their adult lives at work and there are considerable spillover effects in the sense of, that if workplace well-being is inferior, it has negative effects on social relationships and other lifestyle choices.111 It is therefore crucial to consider workplace well-being in the context of overall well-being.36Despite this, workplace initiatives and research on workplace well-being still come up short.112,113 This is mainly due to the broad understanding of the term and the considerable debate about the definition of workplace wellbeing, even going so far, that there is no consensus on the spelling.112

The promotion of employee health and well-being confers several advantages upon the employer. The implementation of this approach has the potential to enhance the productivity of the workforce while simultaneously reducing the number of days absent from work.36,111 Furthermore studies have indicated that for every dollar invested in employee health can save between 1.5 and 5.6 USD in health care spending.111 In consideration of demographic trends, it becomes evident that the implementation of health promotion measures has the potential to extend the duration of participation in the labour market.36 This serves to mitigate the risks associated with demographic change.36,111,114

Furthermore, inadequate health and impaired well-being have a detrimental effect on businesses and, consequently, on the economy.115 It thus falls within the government’s remit to implement regulatory measures in the workplace, with the aim of establishing a baseline standard of health and safety.115 Such regulations include the establishment of maximum working hours, with the objective of preventing overwork, and the implementation of mandatory health checks, as is the case in countries such as France, Japan and Korea. In order to safeguard employees from the detrimental effects of second-hand smoke, countries such as Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom have enacted regulations pertaining to smoking in the workplace.115

In the scientific discourse, there is an emerging argument that the focus of health promotion should shift from the prevention workplace accidents and work-related illnesses to the enhancement of the physical and mental well-being of employees.112 This signifies a transition from the prevention of workplace accidents and illnesses to the promotion of employee health.112

This transformation entails measures focused primarily on the provision of healthier options, encompassing the availability of healthier alternatives in the cafeteria, ergonomic workstations, and sports facilities for breaks.111Additional measures include the dissemination of health information in the form of workshops and other educational initiatives, as well as the implementation of financial incentives such as discounted or fully provided gym memberships or rewards for healthy behaviour.111 An example of providing healthier choices and financial incentives is the Choose Well 365 programme which was implemented in the United States to promote healthier eating in the canteen. Over a period of 12 months, measures such as labelling food with the colours green, yellow, and red were introduced to distinguish between healthy and less healthy options. As an incentive, the employees could earn money if they reached certain purchase thresholds.116 The results showed that after 12 months, participants in the intervention group reduced their purchase of unhealthy products, reduced their daily calorie consumption, and increased the proportion of healthy products purchased. This programme therefore had a positive influence on the eating behaviour of employees and promoted healthier eating in the canteen.111 Another example for financial incentives for both employee and employer is the Healthy Lifestyle Incentive Programme in Salt Lake County in the USA which provided employees with free check-ups, tailored feedback and incentives in the form of points for health-promoting activities, which at the end of the year could be transferred to USD. The programme has resulted in estimated health care savings of 3.5 million USD.111,117,118

Despite the relevance of workplace well-being for the overall well-being and the evidence on the positive effects that workplace measures have on both employees and employers, it is not yet implemented in the majority of the businesses.113 A reason for this is the lack of theory development and overarching frameworks for business implementation.113,119 Although frameworks for research and for implementation exist, due to the complexity of well-being, the frameworks “lack of theoretical models, or indeed conceptual principles, of how to affect change in organisations”113, p.42

References

1 Hudson, J., Kuhner, S. & Lowe, S. The short guide to social policy. (Policy Press, 2015).

2 Dean, H. Social policy. (Polity Press, 2019).

3 Alcock, C., Guy, D. & Edwin, G. Introducing social policy. (Routledge, 2014).

4 Baldock, J., Manning, N., Mitton, L. & Vickerstaff, S. Introduction in Social Policy (eds. Baldock, J. Manning, N., Mitton, L. & Vickerstaff, S.) 1-5 (Oxford University Press, 2011).

5 Béland, D. What is social policy? Understanding the Welfare State. (Polity Press, 2010).

6 Titmuss, R. M. Problems of Social Policy (His Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1950).